SkS Analogy 4 - Ocean Time Lag

Posted on 4 July 2022 by Evan

This is an update to a previous analogy. The original version is here.

Tag Line

Greenhouse gases (GHGs) determine amount of warming, but oceans delay the warming.

Elevator Statement

Try this thought experiment.

- Imagine a pot that holds 8 liters.

- Suspend a thermometer from the the lid so that it hangs in the middle of the pot.

- Put the pot on the stove empty, with no water.

- Turn the burner on very low heat.

- Measure the time it takes for the thermometer to reach 60°C (about 140°F).

To see how water delays the warming, try this thought experiment.

- Using the same pot and stove as before, fill the pot with water.

- Place it on the stove on the same, very low heat.

- Measure the time it takes for the thermometer to reach 60°C (about 140°F).

How much longer does it take to reach 60°C (about 140°F) with water instead of air in the pot? A lot longer!

The longer time required to heat a pot of water than a pot of air explains why there is a delay between GHG emissions and a rise in temperature of the atmosphere: the oceans take a long time to warm up. This is why scientists, such as James Hansen, refer to global warming as an inter-generational issue, because the time lag means that the heating due to our emissions are only fully felt by later generations.

Climate Science

The earth is covered mostly by water. The large heat capacity of the oceans soak up a lot of energy and slow down the heating of the atmosphere. Just how long is the delay between the time we inject CO2 and other GHG's into the atmosphere and when the effect is felt?

For a given CO2 concentration, given enough time and keeping the CO2 concentration constant, we can estimate the final temperature the atmosphere will reach by using the average IPCC estimate of 3°C warming for doubling CO2 concentration (called the “equilibrium climate sensitivity”, ECS). Using the estimate of pre-industrial CO2 concentration of 280 ppm (parts per million), a climate sensitivity of 3°C implies that CO2 concentrations of 350, 450, and 550 ppm yield 1, 2, and 3°C warming, respectively. Using this estimate of climate sensitivity, together with measurements of CO2 from 1970 to today, we can estimate the warming that corresponds to current atmospheric CO2 concentrations. That is, knowing the "burner setting", we can estimate the final temperature of the pot of water, even though we will have to wait some time for it to heat up.

I use the GISS land-ocean data (Goddard Institute for Space Studies) to plot measured global mean temperature above pre-industrial, to estimate the time lag between the temperature anomaly suggested by a particular CO2 concentration and the time when that temperature is observed. This and CO2 concentrations for five selected years are shown in the following figure.

Figure 1. Expected warming based on atmospheric CO2 concentration, using an ECS = 3ºC/doubling CO2, vs committed warming based on measured temperature anomalies (GISS land-ocean data).

Figure 1 indicates 2 things: (1) the time lag between emitting greenhouse gases and when we see the principal effect is about 30 years, due mostly to the time required to heat the oceans, and (2) the rate of temperature increase predicted by a climate sensitivity of 3°C tracks well with the observed rate of temperature increase. As of 2022 we have reached 420 ppm CO2, corresponding to 1.7ºC, if CO2 concentrations remain at current levels.

So whereas the experiment at home with a pot of water on low heat yields a time lag of something like 10’s of minutes to heat the water, to heat an Earth-sized pot of water with GHG's increasing at current rates, the time lag is 10's of years.

Notice in that last sentence I said "with GHG's increasing at current rates." With all of the talk of net-zero emissions, or perhaps just accepting stabilizing CO2 concentration as an acceptable, interim goal, what would happen to the warming and the time lags if we were to stabilize CO2 concentration at 2022 levels? Let's try that thought experiment.

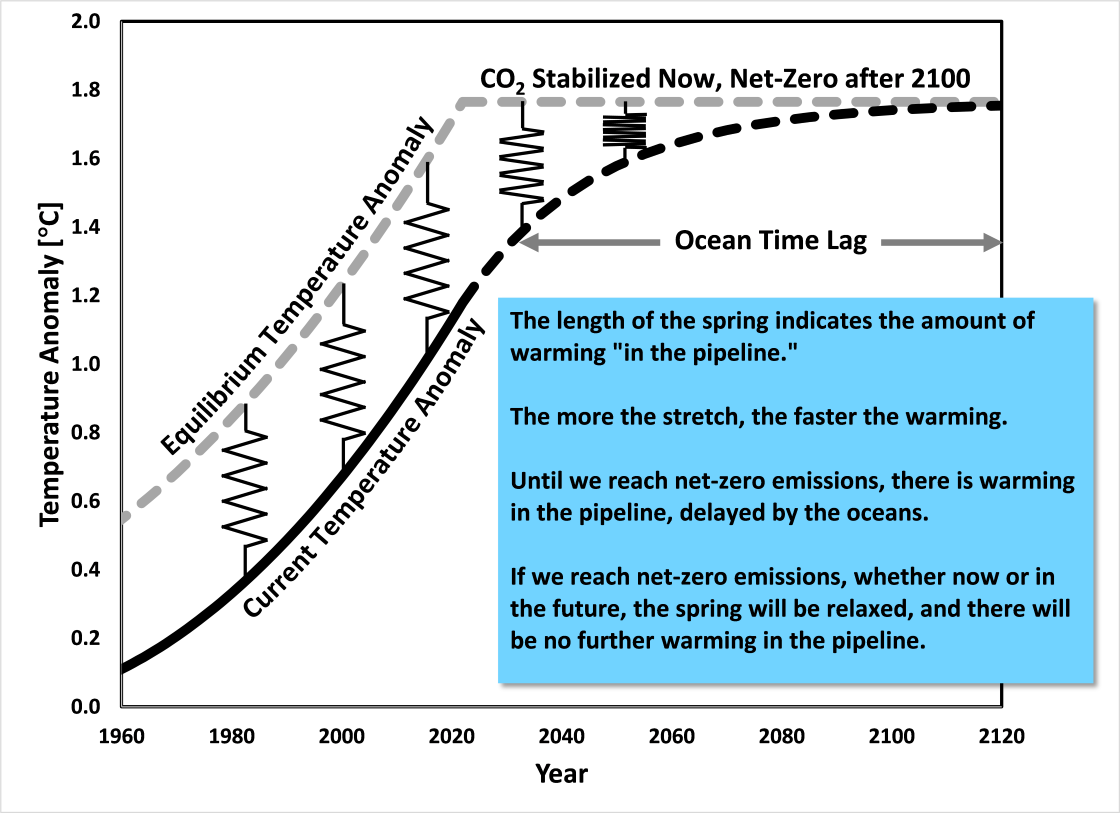

Zeke Hausfather (read here) reports that to stabilize CO2 at current levels, we would need to reduce CO2 emissions by about 70%. To keep CO2 at that level, we would need to continually reduce emissions until we reach net-zero emissions in about 100 years. So the point is that stabilizing CO2 concentration is only an interim goal. Long term, to keep CO2 from rising, we must reach net-zero emissions at some point. Figure 2 shows the hypothetical situation where CO2 is stabilized at 2022 levels for about 100 years, until it reaches net-zero emissions at that point. Think of the temperature difference between committed and equilibrium temperatures as a spring, pulling the committed temperature up to the equilibrium temperature. The oceans resist the action of the spring. Because we have dramatically reduced CO2 emissions from current rates in our thought experiment, instead of the ocean time lag being several decades, it is more like a century.

Figure 2. Temperature trajectory assuming atmospheric CO2 stabilization near 2022. To achieve this trajectory, CO2 emissions must first drop about 70% and then continually decrease until they reach net-zero emissions about 100 years later. About 100 years are required for the temperature to stabilize because of the time required to warm the oceans.

Long story short, the oceans are helping us out a lot by slowing down the warming. Of course, once we warm the earth, the oceans will also slow down the rate of cooling, should we ever try a global-cooling experiment. The ocean time lag works both ways.

Arguments

Arguments

Evan,

This is a good update of the presentation of the technical points regarding future global temperatures.

The future depends on the rapidity of changes (or delay of changes) of how humans live to limit the harm done by accumulating global warming impacts. The future temperature depends on the collective actions by humans today and in the future. And the tragic starting point is the current damage done and the time required for the massive required corrections of how people live due to the lack of responsible limiting of harmful over-consumption through the past 30 years.

I have one important point of elaboration.

In addition to climate “... scientists, such as James Hansen, refer(ring) to global warming as an inter-generational issue, because the time lag means that the heating due to our emissions are only fully felt by later generations.”, policy development experts such as Stephen M. Gardiner have presented the ethical and moral hazard of expecting the developed socioeconomic-political systems to effectively and equitably limit the damaging climate change impacts. Developing sustainable solutions requires significant systemic changes.

Stephen M. Gardiner’s book “A Perfect Moral Storm: The Ethical Tragedy of Climate Change” presents an important perspective (note it was written in 2011). The book should be read in its entirety. But a reasonable understanding can be obtained by reading the abstract and the summary statements regarding each chapter of the contents on the following Oxford University Press Scholarship Online website for the book.

The following is a key point in the Abstract: “...the key issue is that the current generation, and especially the most affluent, are in a position to pass on most of the costs of their behavior (and especially the most serious harms) to the global poor, future generations and nonhuman nature. This tyranny of the contemporary is a deeper problem than the traditional tragedy of the commons.”

The ‘human caused global warming and resulting climate change’ problem is a case of some people benefiting from actions that are unsustainable and harmful to others. The ‘benefit by some causing harm to others’ distinguishes the climate change challenge from a tragedy of the commons problem (where all those benefiting from the commons are harmed by the collective damage and over-consumption). And human caused global warming is not the only development where Others who are harmed have little or no ability to limit the harm done to them and get those who harm them to make full amends and reparations for the harm done.

Rather than just saying global warming is inter-generational, it is important to understand that human caused global warming is one of many developed international and inter-generational tragedies that the developed systems fail to effectively govern because the people who benefit from the damaging unsustainable activity can, and will, misleadingly manipulate public beliefs to powerfully compromise the governing of things and to protect their interests.

OPOF thanks for your references and comments.

Some are quick to note that 10% of the people cause 50% of the GHG emissions (read here). Get rid of the 10% of the biggest emitters (that probably includes me), and we still have a monumental problem.

I think about the harm my emissions are doing, and I'm trying to minimize them. I drive an EV, eat predominantely vegetarian, planning to install geothermal heat pumps for home heating/cooling. I don't fly for pleasure anymore. But my GHG emissions are still unsustainably high, and I don't know what to do about it. I care about those suffering the consequences of my actions, but simply don't know how to drop my emissions to a sustainable level.

It is not just the wealthy, greedy people causing the problem. It is also ordinary, decent, hard-working people who have grown up in an age where fossil fuels power society. Many acts of kindness and charity carry a carbon footprint. It is impossible to do anything in our society without some level of carbon emission.

And this is part of what makes it such an insidious problem to solve.

Evan,

It appears that you may be doing the most that can be expected of a individual – pursue increased awareness and improved understanding and apply it to be less harmful and more helpful. But changes of individual actions are only part of the solution (note: ‘individualism’ is identified as a specific strategy of ‘discourse of climate (action) delay’ presented in the Cambridge Core article “Discourses of climate delay” that is referred to by the Desmog article “Climate Deniers and the Language of Climate Obstruction” that BaerbelW provided a link to in comment 1 on the SkS post “Skeptical Science tackles 'discourses of climate delay' and 'solutions denial'”.)

The following quote about the ‘individualism discourse’ is from the Cambridge Core presentation:

“Who is responsible for taking climate action? Policy statements can become discourses of delay if they purposefully evade responsibility for mitigating climate change. A prominent example is individualism, which redirects climate action from systemic solutions to individual actions, such as renovating one's home or driving a more efficient car. This discourse narrows the solution space to personal consumption choices, obscuring the role of powerful actors and organizations in shaping those choices and driving fossil fuel emissions (Maniates, Reference Maniates2001). Blame shifting in this way can be explicit – “Yale's guiding principles are predicated on the idea that consumption of fossil fuels, not production, is the root of the climate change problem” (Yale University). But it can also be implicit, such as in the social media campaign run by BP – “Our ‘Know your carbon footprint’ campaign successfully created an experience that not only enabled people to discover their annual carbon emissions, but gave them a fun way to think about reducing it – and to share their pledge with the world.”

This is not to suggest that individual actions are futile. Rather, a more productive discourse of responsibility would focus attention on the collective potential of individual actions to stimulate normative shifts and build pressure towards regulation. It would also recognize that regulations and structural shifts are complementary to supporting individual behaviour change.”

Note that in spite of Yale University producing/hosting Yale Climate Connections the high level position of Yale is less helpful than it could be.

So, in addition to pursuing increased awareness and improved understanding of how to change what you do to reduce the harm done by what you do, it is important to politically engage in efforts to help others be more aware and better understand the required changes to help achieve and improve on the Sustainable Development Goals (less global warming helps). One way to do that is to understand the importance of, and ways to improve, political policy pursuits like Green New Deals. One improvement I note regarding most Green New Deal presentations is adding mention of the importance of limiting consumption combined with limiting how harmful the remaining consumption is.

That circles back to the 10% causing 50% concern you raised. The better way to think about the solution is that a major problem is the desires of the other 90% to develop to be like the ‘10% most superior humans’. Those ‘10% most superior humans’ need to set a ‘superior’ sustainable example for the 90% to aspire to. They need to dramatically reduce their consumption and constantly pursue ways for their reduced consumption to be less harmful and more helpful to others including future generations.

As far as helping others, I would suggest you can relax about concerns that you personally fail to be more helpful to those who live less than a decent basic life. That guilt trip is part of the ‘individualism discourse of delay’. My perspective is that collective government action at all levels (municipal up to national and international) is the best mechanism to help people sustainably improve their lives to at least decent basic lives. Acts of charity should be able to focus on the joy, for the charity giver and recipient, of providing improvements beyond that basic decent life. It is a tragedy to expect individual actions to address a systemic problem like a portion of the population not being able to live at least a decent basic life. Economic development can only be part of the systemic solution to poverty if the economic activity is sustainable and harmless. That said, I support groups like Red Cross, Food Banks, pursuits of sustainable assistance for the Homeless, Amnesty International ...