Scientists have detected an acceleration in sea level rise

Posted on 27 February 2018 by John Abraham

As humans emit heat-trapping gases like carbon dioxide, the planet warms, and over time consequences become more apparent. Some of the consequences we are familiar with – for instance, rising temperatures, melting ice, and rising sea levels. Scientists certainly want to know how much the Earth has changed, but we also want to know how fast the changes will be in the future to know what the next generations will experience.

One of the classic projections into the future is for sea level rise. It is expected that by the year 2100, the ocean levels will rise a few feet by the end of the century. This matters a lot because globally, 150 million people live within three feet of current ocean levels. We have built our modern infrastructure based on current ocean levels. What happens to peoples’ homes and infrastructure when the waters rise?

But projecting ocean levels into the future is not simple; we need good data that extends back decades to understand how fast the climate is changing. The classic way to measure ocean levels is by using tide gauges. These are placed just offshore, around the globe to get a sense of how the ocean levels are changing. The problem with tide gauges is they only measure water levels at their location, and their locations are always near shore.

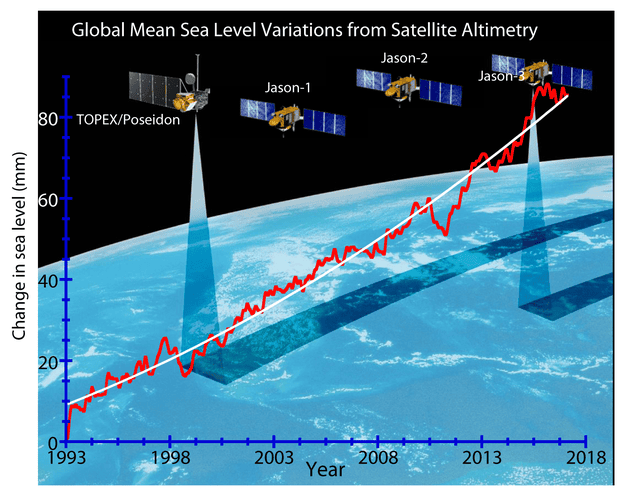

In order to get a better sense of how oceans are changing everywhere, a complementary technology called satellite altimetry is used. Basically, the satellites shoot a radar beam from space to the ocean surface and watch for the reflection of the beam back to space. From this beam, the satellite can calculate the height of the water. Satellites can emit beams continuously as the satellite passes over open oceans, and can gather data far from shorelines. In doing so, they provide the equivalent of a global network of nearly half a million tide gauges, providing sea surface height information every 10 days for over 25 years.

Just recently, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a paper has been published that collects all the available satellite altimetry data and asks whether the sea level rise is accelerating. The authors of the paper are a well-respected team and include Dr. Steven Nerem from the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) and Dr. John Fasullo, from the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

The authors collected data from four generations of satellites that have carried out this altimetry task. The most recent satellite is called Jason 3, launched in 2016. The satellites generate the data shown below. While in any given year ocean levels may rise a bit or fall a bit, the authors focused on the long-term trend (the white line). They found that the long-term trend is, indeed, accelerating. The rate of acceleration is approximately 0.084 mm per year per year. That may not sound like much, but were this rate of acceleration to continue (a conservative estimate), the authors project that by the end of the century oceans with rise approximately 65 cm (more than two feet).

Satellite altimetry data. Illustration: John Fasullo

In the study, the authors quantified what was causing the ocean waters to rise. Part of the rise is related to what’s called thermal expansion (warmer water is less dense so it expands). In the past, this was responsible for the majority of sea level rise. More recently, however, melting ice has contributed more and more to sea level rise. As land-based ice melts, the liquid water flows into the oceans and increases the mass of water in the oceans.

The two largest ice sheets (also the two largest contributors to sea level rise) are found on Greenland and Antarctica. There are other sources of melting ice, such as mountain-top glaciers that also are contributing, but the lion’s share of melting contribution is from the Greenland and Antarctica ice sheets.

Is this acceleration very important?

Arguments

Arguments

As pointed out by Dr Abraham, sea level rise is primarily caused by loss of polar ice and, to a lesser extent, thermal expansion of water. The prediction of a 65 cm. rise in sea level by 2100 appears to be based on the assumption that loss of polar ice does not change over the next 82 years.

Is this true – or is the rate of polar ice loss likely to accelerate? The latter seems certain, a view supported by eminent specialist climate scientists, including Drs. Rignot, Velicogna and Hansen, who point to on-going acceleration in the rate of ice loss from the three polar ice sheets.

They point to Arctic amplification which is accelerating both surface melt and glacier discharge from the Greenland Ice Sheet and to the effects of formation of warming bottom water on the West Antarctic Ice sheet grounded on the seabed. These developments can only result in much more rapid acceleration of mean global sea level rise.

How much will sea level rise by 2100? At present, this can not be accurately determined but a multi-metre rise by 2100 is certainly possible and is becoming increasingly likely with accelerating polar ice mass loss.

I thought much the same as Riduna. It's human nature to try to reach personal conclusions on what it all means, even if the data is not 100% conclusive. I think a smart assessment would be definitely one metre by end of century, with a very distinct possibility of more.

Multiple factors are accelerating, and in some cases, interaction effects could increase the rate of acceleration (e.g., flows of warmer air and sea currents into the Arctic, combined with declining sea ice area, volume and quality, reduced albedo, sunlight penetration into open water, interactions with seabed carbon, etc.). One has to think systematically when making predictions for rate of sea level rise.

I think the melting rate of ice is also likely to increases and increasing the rate of sea level rise as well. Since the environment is connected to each other just one change in one part of the cycle can cause a change to a whole cycle, in this case, the factors are not only the temperature rises up but it also warm currents that run-pass ice sheet as well. So I'm sure that sea level will rise much faster than now, in just a few years, if we can't make an impact big enough to stop temperature rise.