Arguments

Arguments

Software

Software

Resources

Comments

Resources

Comments

The Consensus Project

The Consensus Project

Translations

Translations

About

Support

About

Support

Latest Posts

- Fact brief - Do solar panels generate more waste than fossil fuels?

- Zeke's 2026 and 2027 global temperature forecasts

- 2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #51

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #51 2025

- What are the causes of recent record-high global temperatures?

- Fact brief - Are toxic heavy metals from solar panels posing a threat to human health?

- Emergence vs Detection & Attribution

- 2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #50

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #50 2025

- The rest of the world is lapping the U.S. in the EV race

- Fact brief - Are electromagnetic fields from solar farms harmful to human health?

- Comparing climate models with observations

- 2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #49

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #49 2025

- Climate Adam & Dr Gilbz - Paris Climate Agreement At 10: Did It Do Anything?

- Fact brief - Does the recent slowdown in Arctic sea-ice extent loss disprove human-caused warming?

- Why the chemtrail conspiracy theory lingers and grows – and why Tucker Carlson is talking about it

- 2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #48

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #48 2025

- Consensus machines

- Just have a Think - How an African energy revolution could save ALL of us.

- A girl’s grades drop every summer. There’s an alarming explanation.

- 2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #47

- Fact brief - Are changes in solar activity causing climate change?

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #47 2025

- Exploring newly released estimates of current policy warming

- Climate Adam - Why the Climate Crisis is a Health Crisis

- Super pollutants are trendy, but we should be careful how we use them

- 2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #46

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #46 2025

Archived Rebuttal

This is the archived Intermediate rebuttal to the climate myth "Wind turbines are a major threat to birds, bats, and other wildlife.". Click here to view the latest rebuttal.

What the science says...

|

Wind power is a relatively minor source of mortality for birds compared to climate change, which threatens two-thirds of all North American bird species with a heightened risk of extinction. |

According to the National Audubon Society, two-thirds of all North American bird species are at heightened risk of extinction due to climate change.1 Wildfires will destroy the nesting grounds of many species2, while extreme heatwaves will render their typical habitats uninhabitable.2 For example, the American Goldfinch is projected to lose 65% of its range under a scenario of 3 degrees Celsius global warming, while the Allen’s Hummingbird is projected to lose 64% of its range.2

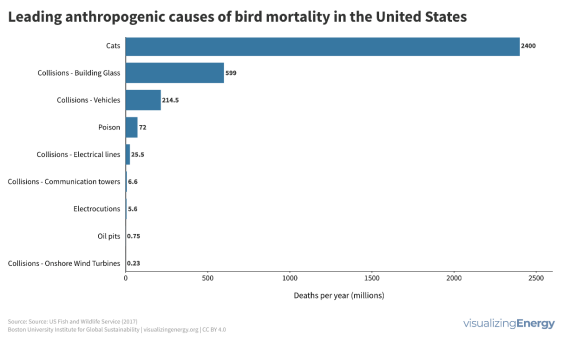

By contrast, wind power is a relatively minor source of mortality for birds. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has estimated that, throughout the United States, cats kill an average of 2.4 billion birds per year, and collisions with building glass kill an average of 599 million birds, while wind turbines kill an average of 234,000 birds per year.3 Collisions with electrical lines cause an average of 25.5 million deaths per year, a number that could grow with the construction of new transmission lines to connect wind projects (and other renewables) to the grid.3 These mortality figures rely on studies dating back to 2013 or 2014 and may be outdated due to the fact that there were fewer wind turbines 10 years ago than there are today.4 However, research has found that wind power causes far fewer bird deaths than fossil fuels per unit of energy output, a metric that is not sensitive to the total number of wind turbines installed. While fossil fuels cause 5.2 avian fatalities per GWh, wind turbines cause only 0.3–0.4 avian fatalities per GWh (Sovacool 2013).5

Figure 1: Leading anthropogenic causes of deaths to birds in the United States. Source: Boston University Institute for Global Sustainability.6

The impacts of wind development on certain bat species may be more severe. One study published in 2021 estimated that the population of hoary bats in North America could decline by 50% by 2028 without adoption of measures to reduce fatalities (Friedenberg & Frick 2021).

However, actionable steps can be taken to reduce bird and bat fatalities from wind turbines. With respect to birds, most deaths occur when turbines are sited near nesting places. Siting facilities to avoid where birds nest, feed and mate, as well as where they stop when migrating, has proved successful at reducing fatalities.5 In addition, the wind turbine components that pose the greatest risk to birds are the blades and tower. The relatively simple action of painting the tower black has been shown to reduce deaths of ptarmigans (a bird in the grouse family) by roughly 48% (Stokke et al. 2020), while painting one of the blades black has reduced deaths by 70% (May et al. 2020).7 Other successful methods include slowing or stopping turbine motors when vulnerable species are present, in order to reduce the likelihood of collisions.8 Deployment of this method in Wyoming has contributed to an 80% decline in eagle fatalities (McLure et al. 2021). With respect to bats, strategies to minimize fatalities include curtailment (i.e., stopping wind turbines from spinning under certain circumstances), as well as ultrasonic acoustic deterrents (Friedenberg & Frick 2021) and visual deterrents.9 In 2022, the U.S. Department of Energy awarded $7.5 million in research grants to study bat deterrent technologies.10

Overall, though it remains difficult to eliminate the risk of collisions entirely, wind power can ultimately help to protect bird and bat populations by displacing fossil fuels and mitigating climate change impacts.11

Footnotes:

[1] Audubon Society, Survival by Degrees: 389 Bird Species on the Brink, Nat’l. Audubon Soc’y. (last visited March 25, 2024).

[2] Audubon Society, How Wildfires Affect Birds, Nat’l. Audubon Soc’y. (last visited March 25, 2024).

[3] Threats to Birds, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (last visited March 25, 2024).

[4] Do wind turbines kill birds? MIT Climate Portal (Aug. 17, 2023) - noting that the cited studies were published in 2013 and 2014, and the numbers are likely to be higher today because more wind farms have been built since then.

[5] Sovacool’s 2013 study explains that fossil fuels cause avian fatalities upstream during coal mining, through collision and electrocution with operating plant equipment, and indirectly through acid rain, mercury pollution, and climate change (see [4] at 21). The study is based on operating performance in the United States and Europe. Id. at 19. Note that an earlier version of Sovacool’s study, published in 2009, was critiqued for conflating birds and bats, among other issues; Sovacool responded directly to these critiques in a 2010 article and addressed many of them in the 2013 version of the study that is cited in this report. See Craig K.R. Willis, et al., Bats are not birds and other problems with Sovacool’s (2009) analysis of animal fatalities due to electricity generation, 38 Energy Policy 2067 (2010); Benjamin K. Sovacool, Megawatts are not megawatt-hours and other responses to Willis et al., 38 Energy Policy 2,070 (2010) (responding to critiques raised about an earlier version of the study on the avian benefits of wind energy).

[6] Cutler Cleveland et al., Is Wind Energy a Major Threat to Birds?, Visualizing Energy, Oct. 9, 2023.

[7] see also Neel Dhanesha, Can Painting Wind Turbine Blades Black Really Save Birds, Audubon Magazine, Sep. 18, 2020.

[8] U.S. Dep’t. of Energy Wind Energy Technologies Office, Environmental Impacts and Siting of Wind Projects, U.S. Dep’t of Energy: Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (last visited March 25, 2024).

[9] Chapter 4: Minimizing Collision Risk to Wildlife During Operations: Minimization: Deterrence, Renewable Energy Wildlife Inst. (Dec. 27, 2022).

[10] U.S. Dep’t. of Energy Wind Energy Technologies Office, DOE Wind Energy Technologies Office Selects 15 Projects Totaling $27 Million to Address Key Deployment Challenges for Offshore, Land-Based, and Distributed Wind, U.S. Dep’t of Energy, Sep. 21, 2023.

[11] Audubon Society, Wind Power and Birds, Nat’l. Audubon Soc’y. (Jul. 21, 2020).

This rebuttal is based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in 2024. Skeptical Science sincerely appreciates Sabin Center's generosity in collaborating with us to make this information available as widely as possible.

Updated on 2024-09-01 by Ken Rice.

THE ESCALATOR

(free to republish)