Positives and negatives of global warming

What the science says...

| Select a level... |

Basic

Basic

|

Intermediate

Intermediate

|

Advanced

Advanced

| ||||

|

Negative impacts of global warming on agriculture, health & environment far outweigh any positives. |

|||||||

Climate Myth...

It's not bad

"By the way, if you’re going to vote for something, vote for warming. Less deaths due to cold, regions more habitable, larger crops, longer growing season. That’s good. Warming helps the poor." (John MacArthur)

At a glance

“It's not going to be too bad”, some people optimistically say. Too right. It's going to be worse than that. There are various forms this argument takes. For example, some like to point out that carbon dioxide (CO2) is plant-food – as if nobody else knew that. It is, but it's just one of a number of essential nutrients such as water and minerals. To be healthy, plants require them all.

We know how climate change disrupts agriculture through more intense droughts, raging floods or soil degradation – we've either experienced these phenomena ourselves or seen them on TV news reports. Where droughts intensify and/or become more prolonged, the very viability of agriculture becomes compromised. You can have all the CO2 in the world but without their water and minerals, the plants will die just the same.

At the same time, increased warming is adversely affecting countries where conditions are already close to the limit beyond which yields reduce or crops entirely fail. Parts of sub-Saharan Africa fall into this category. Elsewhere, many millions of people – about one-sixth of the world’s population - rely on fresh water supplied yearly by mountain glaciers through their natural melt and regrowth cycles. Those water supplies are at risk of failure as the glaciers retreat. Everywhere you look, climate change loads the dice with problems, both now and in the future.

Please use this form to provide feedback about this new "At a glance" section. Read a more technical version below or dig deeper via the tabs above!

Further details

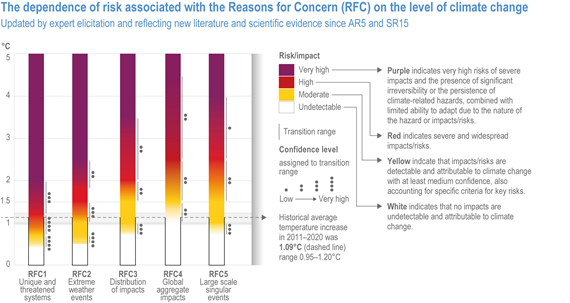

Most climate change impacts will confer few or no benefits, but may do great harm at considerable costs. We'll look at the picture, sector by sector below figure 1.

Figure 1: Simplified presentation of the five Reasons for Concern burning ember diagrams as assessed in IPCC AR6 Working Group 2 Chapter 16 (adapted from Figure 16.15, Figure FAQ 16.5.1).

Agriculture

While CO2 is essential for plant growth, that gas is just one thing they need in order to stay healthy. All agriculture also depends on steady water supplies and climate change is likely to disrupt those in places, both through soil-eroding floods and droughts.

It has been suggested that higher latitudes – Siberia, for example – may become productive due to global warming, but in reality it takes a considerable amount of time (centuries plus) for healthy soils to develop naturally. The soil in Arctic Siberia and nearby territories is generally very poor – peat underlain by permafrost in many places, on top of which sunlight is limited at such high latitudes. Or, as a veg-growing market gardening friend told us, “This whole idea of "we'll be growing grains on the tundra" is just spouted by idiots who haven't grown as much as a carrot in their life and therefore simply don't have a clue that we need intact ecosystems to produce our food.” So there are other reasons why widespread cultivation up there is going to be a tall order.

Agriculture can also be disrupted by wildfires and changes in the timing of the seasons, both of which are already taking place. Changes to grasslands and water supplies can impact grazing and welfare of domestic livestock. Increased warming may also have a greater effect on countries whose climate is already near or at a temperature limit over which yields reduce or crops fail – in parts of the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa, for example.

Health

Warmer winters would mean fewer deaths, particularly among vulnerable groups like the elderly. However, the very same groups are also highly vulnerable to heatwaves. On a warmer planet, excess deaths caused by heatwaves are expected to be approximately five times higher than winter deaths prevented.

In addition, it is widely understood that as warmer conditions spread polewards, that will also encourage the migration of disease-bearing insects like mosquitoes, ticks and so on. So long as they have habitat and agreeable temperatures to suit their requirements, they'll make themselves at home. Just as one example out of many, malaria is already appearing in places it hasn’t been seen before.

Polar Melting

While the opening of a year-round ice-free Arctic passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans would have some commercial benefits, these are considerably outweighed by the negatives. Detrimental effects include increased iceberg hazards to shipping and loss of ice albedo (the reflection of sunshine) due to melting sea-ice allowing the ocean to absorb more incoming solar radiation. The latter is a good example of a positive climate feedback. Ice melts away, waters absorb more energy and warming waters increase glacier melt around the coastlines of adjacent lands.

Warmer ocean water also raises the temperature of submerged Arctic permafrost, which then releases methane, a very potent greenhouse gas. The latter process has been observed occurring in the waters of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf and is poorly understood. At the other end of the planet, melting and break-up of the Antarctic ice shelves will speed up the land-glaciers they hold back, thereby adding significantly to sea-level rise.

Ocean Acidification

Acidity is measured by the pH scale (0 = highly acidic, 7 = neutral, 14 = highly alkaline). The lowering of ocean pH is a cause for considerable concern without any counter-benefits at all. This process is caused by additional CO2 being absorbed in the water. Why that's a problem is because critters that build their shells out of calcium carbonate, such as bivalves, snails and many others, may find that carbonate dissolving faster than they can make it. The impact that would have on the marine food-chain should be self-evident.

Melting Glaciers

The effects of glaciers melting are largely detrimental and some have already been mentioned. But a major impact would be that many millions of people (one-sixth of the world’s population) depend on fresh water supplied each year by the seasonal melt and regrowth cycles of glaciers. Melt them and those water supplies, vital not just for drinking but for agriculture, will fail.

Sea Level Rise

Many parts of the world are low-lying and will be severely affected even by modest sea level rises. Rice paddies are already becoming inundated with salt water, destroying the crops. Seawater is contaminating rivers as it mixes with fresh water further upstream, and aquifers are becoming saline. The viability of some coastal communities is already under discussion, since raised sea levels in combination with seasonal storms will lead to worse flooding as waves overtop more sea defences.

Environmental

Positive effects of climate change may include greener rainforests and enhanced plant growth in the Amazon, increased vegetation in northern latitudes and possible increases in plankton biomass in some parts of the ocean.

Negative responses may include some or all of the following: further expansion of oxygen-poor ocean “dead zones”, contamination or exhaustion of fresh water supplies, increased incidence of natural fires and extensive vegetation die-off due to droughts. Increased risk of coral extinction, changes in migration patterns of birds and animals, changes in seasonal timing and disruption to food chains: all of these processes point towards widespread species loss.

Economic

Economic impacts of climate change are highly likely to be catastrophic, while there have been very few benefits projected at all. As long ago as 2006, the Stern Report made clear the overall pattern of economic distress and that prevention was far cheaper than adaptation.

Scenarios projected in IPCC reports have repeatedly warned of massive future migrations due to unprecedented disruptions to global agriculture, trade, transport, energy supplies, labour markets, banking and finance, investment and insurance. Such disturbances would wreak havoc on the stability of both developed and developing nations and they substantially increase the risk of future conflicts. Furthermore, it is widely accepted that the detrimental effects of climate change will be visited mostly on those countries least equipped to cope with it, socially or economically.

These and other areas of concern are covered in far more detail in the 36-page Summary for Policymakers from the IPCC AR6 Synthesis Report, released in March 2023. The report spells out in no uncertain terms the increasingly serious issues Mankind faces; the longer that meaningful action on climate is neglected, the greater the severity of impacts. The report is available for download here.

Last updated on 21 April 2023 by John Mason. View Archives

Arguments

Arguments

[DB] Please familiarize yourself with this site's Comments Policy; additionally, please read the Big Picture post.

Finally, commenting at Skeptical Science works best if you first limit the scope of your comment to that of the thread on which you post your comment and then follow up on those threads to see what respondents have said in response to you. There are quite literally thousands of threads here at SkS; if you do not engage with the intent to enter into a dialogue to discuss the OPs of the threads on which you place comments, you invite moderation of your comments.

Note that your first statement is an unsupported assertion. When making assertions counter to that which is the understood state of the science, it is customary here to then also furnish a link to a reputable source which supports your assertion.

Having occasionally lurked for some time on SkS, I have a longstanding question for anyone who like to take a crack at it. I'd like to be able to offer to some of my skeptical friends and family an example of how AGW might be falsified. Let's say I'm conversing with a skeptic who (perhaps grudgingly) admits the reality of modest AGW but who considers it nothing to fret over, and certainly nothing to justify government intervention. Is there some precise, quantifiable outcome I can predict will obtain within 20 years from now if C02 remains above 400 ppm (or 450 or 500 or whatever), such that if it doesn't happen, I would have to concede I was mistaken as a "warmist"? Something along the lines of Haldane's famous rabbit in the Cambrian? Something I could place money on and collect in 2033?

For example, could I say, if C02 remains above 400 ppm, then if by 2033 the global sea level average hasn't risen by at least 6 inches (or whatever) or the surface area of the Maldives has not been reduced by 10% (or whatever) or the Antarctic has not lost more than 5% (or whatever) of its ice volume or some other precise costly catastrophe does not occur before then, then we warmists were all mistaken?

@KenD 50 years of cooling whilst atmospheric CO2 continues to rise, without evidence of substantial changes in the other forcings would constitute a pretty sound falsification I would have thought. The good thing is that many climate models are available in the public domain, so at least the models are easily falsifiable by plugging in the observed forcings and seeing if the models can explain the observed climate.

Sure, KenD.

1. Arctic sea ice will be effectively (<250k km2 area) gone in ten years at summer minimum. According to Funder et al. (2011), Arctic sea ice extent hasn't been lower than current in about 8000 years. The trend is currently greater-than-linear, and the linear trend has it effectively disappearing at summer minimum within eight years, about 70 years ahead of IPCC AR4 projections. Even if we remain stable at 400ppm, sea ice is going to continue to decline thanks to the oceans continuing to move toward their equilibrium climate response to the stabilized forcing.

2. Antarctic and Greenland land ice loss will continue over the next decade at least at the current rate found in Shepherd et al. (2013).

3. Within fifty years, the process of ecological deconstruction or dis-integration will be obvious. Species that can move rapidly will leave their niches and attempt to establish equilibria within environments.more suitable to their current configurations. That may leave some slower and more interdependent species in the lurch. Species may also respond genetically. Then there are species that are up against the wall. A wide range of studies, if academia is alive and well, should be reporting this type of significant change in the biosphere (already occurring, actually).

In other words, KenD, you don't have to wait for 2033. You can win that bet right now.

KenD,

20 years is too short of a time frame, and making any one (or three) specific projections is dicey. We're running a one-time experiment that has never happened in the past 100 million years... if ever. There is no solid way to predict exactly what will happen when. We know that bad things are going to start to happen now, but even then, no one will be able to connect the dots and unequivocally say "this is due to climate change."

But things will get progressively worse. The day will come in ten, twenty, or thirty years (maybe more, but I don't think so) when so many different things are happening and changing that the costs will be horrendous.

With that said, whenever that day comes... there will still be more warming in the pipeline. Climate change takes time, even though we have accelerated the process by a factor of 100. So when the day comes that (if you could pick the right variables) you win your bet, it will already be way, way too late to do anything about it. The genie will be out of the bottle. And things will continue to get worse from there.

My favorite analogy for his is the man who jumped off of the roof of a skyscraper, and whenever he passed an open window, he was heard to say "So far, so good."

But, to return to your question: no, I don't think so. There is no one particular parcel of evidence that you can reliably pick now, especially in a time frame as short as 20 years.

Thanks for your helpful responses, DSL, Sphaerica, and Dikran. I'll see if one of my friends is willing to make a wager on the following, assuming we stay at or above current C02 levels (just shy of 400 ppm):

If total ice sheet loss over the next 10 years is less than 3.44 trillion tons (344 billion tons times 10 years), then he wins and I lose.

If Arctic sea ice is > 250k km2 area in 2023 at summer minimum, then he wins and I lose.

The friend I'm thinking of is a fan of WattsUpWithThat, so I'm hopeful he'd be willing to bet on the above. I'm assuming these are pretty safe bets on my part?

KenD:

Instead of looking at the next 20 years, why don't you dig up some predictions made in the past - e.g., Arrhenius in 1896 - that have come true?

KenD.

Bet on volume rather than area, and you will almost certainly have money in the bank.

And sadly, Sphaerica is correct about time spans and realisations. The only slight point at which I would diverge is that I suspect that the genie's already been out of the bottle for a few years.

Thanks, Bob and Bernard. Bob, I looked through some of the Arrhenius article, but I confess I'm not technical enough to home in on the best example of a prediction he made that has since come true. Bernard, if you were to place a bet on the minimum volume of Artic sea ice by 2023 (assuming C02 levels remain at or above current levels), what value you would bet on, assuming you want to keep your money safe?

What about Figure 1 of this paper?

Oops. I forgot to include the link:

The Economic Effects of Climate Change

Mark @344 - first off, almost all of the estimates in the Tol paper you reference are from the most conservative economists doing climate research (Nordhaus, Tol, Mendelsohn, etc.), so the paper almost certainly underestimates the economic damage from climate change (probably by a very large amount, in my opinion). It's really interesting that it references Chris Hope, who now says that the social cost of carbon is in the ballpark of $150 per tonne of CO2, which is 1-2 orders of magnitude higher than Tol believes.

Despite these underestimates, the paper still concludes that the net impact on GDP at 2.5°C will be negative, and we're already committed to about 1.5°C warming and still rising fast. So I'm not really sure what your point is.

Richard Tol is a conservative? That might be news to him! But OK...what do the "non-conservative" ("liberal?") economists say?

Mark Bahner @ 346:

New NASA study accepted by Geophysical Research Letters (Lau et al.) quantifies that wet places will get wetter and dry places will get drier--more floods and drought. Heavy rain will increase, light rain will increase slightly, but moderate rain will decrease and no rain will be more frequent. There is a summary with video of global map of changes.

I'm not sure where to post this inquiry, and this thread seems the best, so it'll go here.

I posted a link, a couple of weeks ago now, to a paper shared by Skeptical Science's Facebook page, onto my own feed.

This resulted in an intense discussion with a pseudo-skeptic. Naturally, it had nothing particularly to do with the paper. Among the various arguments was one I have not encountered before, which was made in reply to a point I made about the problems related to the rate of current change:

I didn't pick up on the obvious misrepresentation ("Your whole augment then is based not on the actual level of CO2 or temperature but that you can determine what the gradient of CO2 has been over the last 200 million years") at the time.

Anyway, my university calculus is, charitably put, rusty, so while I strongly suspect this claim is a load of bollocks (the notion that vast swathes of experimentally-verified atmospheric physics can be upended by basic multivariable calculus strikes me as ridiculous in the extreme) I'm not in a position to make a strong rebuttal (I did note that, indeed, trying to appeal to a principle of maths as a way of evading the evidence is bunk).

Are there any other suggestions for rebutting this claim?

Our current CO2 emissions rate is ten times faster than the rate which preceded the end-Permian extinction, 250 million years ago. Also, I've pointed out that fossilized leaves from the PETM confirm that a rapid CO2 increase (still not as fast as today's) stresses ecosystems.

Scientists use more evidence than just first year calculus to determine climate sensitivity to CO2. Here's a figure from Royer et al. 2007 (PDF) which concludes that “a climate sensitivity greater than 1.5°C has probably been a robust feature of the Earth’s climate system over the past 420 million years”.