Lobbying against key US climate regulation ‘cost society $60bn’, study finds

Posted on 10 June 2019 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Carbon Brief by Josh Gabbatiss

Political lobbying in the US that helped block the progress of proposed climate regulation a decade ago led to a social cost of $60bn, according to a new study.

Environmental economists Dr Kyle Meng and Dr Ashwin Rode have produced what they believe is the first attempt to quantify the toll such anti-climate lobbying efforts take on society.

The pair say their work reveals the power firms can have in curtailing government action on climate change, in the face of “overwhelming evidence” that its social benefits outweigh the costs, which range from reduced farming yields to lower GDP.

Crucially, they found that the various fossil-fuel and transport companies expecting to emerge as “losers” after the bill were more effective lobbyists than those expecting gains.

The authors say their results, published in Nature Climate Change, support the conclusion that lobbying is partly responsible for the scarcity of climate regulations being enacted around the world.

However, they tell Carbon Brief that there is still hope for those seeking to develop effective new climate policies:

“Our bottom line is: climate policy emerges from a political process. We’ve shown that this political process can undermine the chances of passing climate policy. But we’ve also shown that careful design of climate policy can help make it more politically robust to opposition.”

Waxman-Markey

The Waxman-Markey bill, described by the study’s authors as “the most prominent and promising US climate regulation so far”, did not make it past the Senate in 2010, meaning it never passed into law.

However, having passed the House of Representatives in summer 2009, it remains the closest the nation has ever come to implementing wide-ranging climate legislation.

Formally known as the American Clean Energy and Security Act 2009, the bill proposed a 17% cut in US emissions by 2020 – and then 80% by 2050 – based on 2005 levels. It was named after the two Democrat representatives who wrote it, Henry Waxman and Edward Markey.

A key element of Waxman-Markey was its cap-and-trade scheme, which would have limited the amount of greenhouse gases produced nationally while creating a fixed number of tradable emission permits for industry nationwide. Other measures included a renewable energy standard and legislation for energy efficiency and grid modernisation.

The bill was the culmination of several attempts stretching back to 2003 to pass cap-and-trade legislation limiting the US economy’s emissions. As none of these efforts were successful, president Barack Obama instead relied on the executive powers of the US Environmental Protection Agency to tackle greenhouse gas emissions, specifically its power to regulate “any pollutant” that “endangers public health or welfare”.

Today, with climate change low on the list of federal priorities, there are some state-level ventures in place, such as California’s cap-and-trade system, but still no country-wide scheme.

Climate lobbying

Media reports around the time Waxman-Markey was making its way through the US government made it clear that lobbyists were thought to be hindering its progress.

However, the authors of the new paper note that despite such reporting it is difficult to appreciate the extent of political lobbying and its impact on the final outcome. According to them, lobbying often goes unrecorded and, even when it is, it can prove difficult to quantify which groups stand to gain and lose – and to what extent.

For Waxman–Markey, they made use of the “comprehensive US congressional lobbying record” to piece together a full picture of the situation at the time.

According to their paper, the bill accounted for around 14% of all recorded lobbying expenditures at the time – more spending on lobbying than for any other policy between 2000 and 2016.

A separate study conducted by Dr Robert Brulle of Drexel University in 2018 found that over this period, climate issues took up roughly 4% of all lobbying spend, amounting to over £2bn. He concluded that fossil-fuel, transport and utility companies dominated this activity, with expenditures that “dwarfed” those of environmental groups and renewable energy corporations.

However, some of the highest spenders listed by Meng and Rode in their new paper were those who stood to gain from the bill, such as General Electric and the Pacific Gas and Electric Company.

Winners and losers

To understand different lobbyists’ motivations, the researchers first had to work out how Waxman-Markey would have affected companies had it passed into law.

They took data on prices from a prediction market tied to the bill while it was being considered by government and combined it with stock prices for firms involved in lobbying. In a joint email, Meng and Rode explain how this works to Carbon Brief:

“A prediction market is essentially a betting market where participants bet on the likelihood of some event happening. Think of it like a sports betting market (in other words, will Liverpool win the Champions League final?), but you can do that for any event…The power of a prediction market is that, under some standard economic assumptions, the price of a bet of that market at any point in time reflects the market-held belief that the event will happen.”

Their “innovation”, the pair explain, was to combine this information with the stock market prices of publicly listed firms that lobbied on the bill. They were then able to estimate how the values of publicly listed firms were expected to change if the policy had passed.

One benefit of this approach was that it allowed them to establish, in what they describe as a “hands-off”, objective manner, who the “winners” and “losers” were in the face of climate regulations. This allowed the researchers to bypass both their own preconceptions, as well as any statements made by the firms themselves which, as the pair point out, may not be reliable.

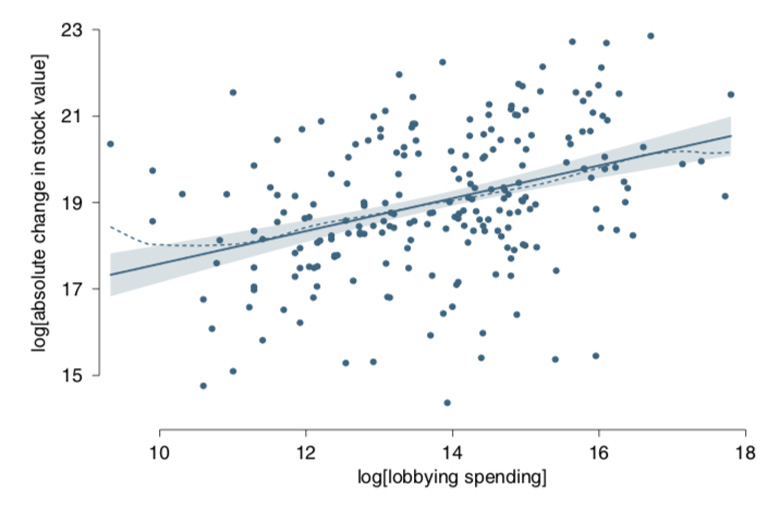

The team found a statistically significant relationship [see graph below] between how much a firm spent on Waxman-Markey lobbying and how much the bill was expected to change its stock value.

The researchers found a significant relationship between the amount a firm spent lobbying on Waxman-Markey (x-axis) and how much the policy was expected to alter its stock value (y-axis). Source: Meng and Rode (2019).

To then understand how these activities affected the final outcome, they built a model that incorporated a game-theory approach to lobbying – where firms try to influence policy for their own benefit – and a standard model of how firms behave under a cap-and-trade policy.

This model revealed that oppositional lobbying – that is to say activities by companies that stood to lose out – was the most effective. This implies the input of “loser” firms, which include Boeing, Marathon Oil, Walmart and Ford, had more influence that “winners”, despite spending comparable sums on lobbying. From this conclusion, the researchers estimated that the sum of all lobbying decreased the probability of the bill being enacted by 13%.

While their work does not resolve the issue of why this disparity between winners and losers exists, the pair tell Carbon Brief they have some ideas:

“The asymmetric effectiveness could be due to differential abilities of firms to collectively organise, gather information on policy consequences and to lobby on other, related issues. While all these explanations are consistent with our findings, data limitations prevent us from examining which one is most relevant for the Waxman-Markey bill.”

Social cost

To pin down the financial impact of lobbying, the researchers built on previous research that placed a $467bn (in 2018 US dollars) price tag on the global social cost of the failed Waxman-Markey bill. This was based on forecasts of greenhouse gas emissions that would have been avoided had it come into force.

The cost of these emissions for the world as a whole are well established, as they explain to Carbon Brief:

“A large body of research has demonstrated the costs of unmitigated climate change in myriad contexts, including decreased agricultural yields, increased conflict, increased mortality and morbidity, decreased labor supply, and lower gross domestic product. Failure to enact Waxman-Markey is expected to have had adverse consequence in all these areas by allowing for higher greenhouse gas emissions and thus higher climate damages.”

Since they found that lobbying increased the likelihood of the bill not passing by 13%, they assigned this share of the total cost to lobbying efforts. This gave them their final figure of $60bn.

Given the current state of climate policy in the US, Meng and Rode conclude by suggesting how this knowledge could be used to build a new strategy that is more likely to be successful.

They took their model and used it to gauge the impact of providing more free credits under the cap-and-trade system to companies – and particularly those that lobbied against the new bill. As this would lead to greater gains or reduced losses, they found it could effectively reduce the amount of anti-bill lobbying and make it more likely to succeed.

While they note such actions could prove unpopular and have unintended political consequences, they suggest this information could nevertheless be incorporated into future policy-making. They tell Carbon Brief:

“Our new point is that if the very likelihood of having climate policy enacted in the first place may be jeopardised by political influences (via lobbying), why not try to use this revenue to neutralise some of the political opposition in a targeted way.”

Meng, K.C. and Rode, A. (2019) The social cost of lobbying over climate policy, Nature Climate Change, www.nature.com/articles/s41558-019-0489-6

Arguments

Arguments

Lobbying isn't going to go away and is a legitimate activity in a free society, but it's just not always a level playing field. How can public interest groups, sometimes fronting poor communities over local environmental issues hope to compete with multi national corporations?

Regarding Waxman-Markey, maybe the firms thinking they would loose just happened to have the best lawyers.

This is relevant, and the first example is the oil industry and the Koch brothers: The best influence money can buy - the 10 Worst Corporate Lobbyists

Why do you say lobbying is legal?

https://priceonomics.com/when-lobbying-was-illegal/

Detailed analysis like this is an important improvement of awareness and understanding of what is really going on. But, as proven by the climate science case, there are limits to the 'uptake' of improvements of awareness and understanding of what is really going on, especially when that improvement would require corrections of developed perceptions of status or developed perceptions of personal opportunity to enjoy life.

The problem is not things like 'lobbying' or 'money in politics'. Those are just examples of actions that can be helpful or harmful to the development of a sustainable and improving future for humanity.

The problem is the success of harmful actions.

Social systems that rely on popularity or profitability to determine Winners and Losers can be seen to encourage the development of harmful selfishness. A lack of governing based on the importance of improving awareness and understanding to help develop a sustainable better future for all of humanity can be expected to produce the observed harmful, and ultimately unsustainable, results.

Leadership that understands and honours the importance of developing a sustainable better future for all of humanity would not be influenced by the type of lobbying or money influence that is succeeding in the USA, unless they believe they risk losing their leadership roles if they try to honour that important understanding.

Leaders compromising what is understandably required in the hope that doing so will improve their chances of 'remaining a leader' is a downward spiral. It resulted in the likes of Donald Trump and Mitch McConnell and the House Freedom Caucus becoming harmfully influential in the USA (and similarly harmful people becoming influential in regions of the USA and in other nations). They become more harmfully powerful the more that the group they lead is compromised by selfish interests such as greed and intolerance.

Competition for status based on popularity and profitability encourages selfishness and discourages helpfulness. It encourages the pursuit of individual perceptions of success any way that can be gotten away with. Ungoverned by the requirement to not harm Others (especially the future generations), and without the aspiration to help others (including the future generations), competitions can be seen to encourage people to be more myopically focused on immediate personal benefit. And that push for short term gain any way that can be gotten away with will result in people forming collectives that are focused on their collective (tribe/corporation) benefits in the short term.

A focus on short term benefits for a sub-set of humanity inevitably dismisses consideration of the need to provide benefits into the future. The sustainability of benefits for the sub-set isn't even a serious consideration. The focus is on how to increase or prolong any developed perceptions of status relative to Others without concern for sustainability.

That lack of consideration for Others and the Future easily extends to a lack of concern for climate impacts, biodiversity loss or other harm being done. The focus on maintaining and increasing perceptions of status relative to Others becomes harmfully all consuming. That harmfully consumptive condition can be seen to have taken over the Political Right in many regions of the planet.

Lobbying is not the Problem. The success of harmful selfishness is the problem. And the ability to legally get away with misleading political marketing prolongs or increases that incorrect and harmful success.

Misleading political marketing causes many leaders to incorrectly harmfully dive into the downward spiral of compromising what is understandably required to be done by responsible helpful leaders.

Populations lose good helpful leadership when misleading political marketing is 'legal'. And the future of humanity loses the most because they do not get to lobby, develop and deliver political messages, vote, protest, or launch lawsuits.

Related to my comment @3, and another exercise in improving my understanding by practising the presentation of it, is the following alternative presentation of the same fundamental abductive reasoned 'explanation of what can be seen to be going on'.

Competition for status judged by popularity and profitability is likely to develop harmful results because it encourages a narrower more selfish worldview. And narrower more selfish worldviews tend to excuse actions perceived to be personally beneficial but are understandably harmful to Others. Self interest can easily develop harmfulness. And those developed harmful results will resist correction. The more popular and profitable an activity becomes the more powerfully it can and will resist losing developed perceptions of status (resisting correction).

Divisiveness in societies develops when misleading marketing creates a large enough group of supporters for a harmfully incorrect understanding that increases or prolongs the popularity or profitability of an unsustainable harmful activity. Good helpful people are not on 'both sides of those harmful divides'.

Regarding the climate science divide, the Good Helpful people include those who try to raise awareness of the extreme but possible levels of harm that could be done to the future of humanity by a lack of rapid correction of the harmful popular and profitable activity that has developed. Evaluations pointing out the harm done to the current day generation by the lack of correction in the past, such as this report, are also helpful. This study points out the future harm done by the lack of correction by people in the past.

The Other side includes people who try to maintain harmfully developed ultimately unsustainable perceptions of status (even people trying to come up with more gradual reductions of the rate of harm done in attempts to maintain developed perceptions of status and prosperity). It also includes people who try to argue that doing harm to the future generations of humanity can be justified by of any of the following harmful misleading marketing claims: