Pinning down climate change's role in extreme weather

Posted on 29 April 2024 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink by Andrew Dessler

In the wake of any unusual weather event, someone inevitably asks, “Did climate change cause this?” In the most literal sense, that answer is almost always no. Climate change is never the sole cause of hurricanes, heat waves, droughts, or any other disaster, because weather variability always plays a primary role in the genesis of the events.

However, climate change can make these events more intense and, given the non-linearities in the damages, this can vastly increase the damage and misery from extreme weather. So quantifying the role of climate change is therefore of great interest.

To do this, scientists turn to extreme event attribution studies. These rely on three separate lines of evidence. The first is the observational record: If you have good observations of the climate over a long enough period, the data set can be statistically analyzed to determine whether the event in question is becoming more frequent as the climate warms.

But correlation does not prove causality, so you need the second line of evidence: a physical understanding of why a particular extreme is getting worse as the climate warms. It should be obvious to readers of this substack why, in a warmer world, we expect to get more frequent heat waves. This physical understanding adds to our con?dence that climate change is a factor in the occurrence of heat waves.

Finally, we look to computer simulations of the climate. The most common approach is to produce two different simulations of the climate: One simulation is of the real world, so it includes increasing greenhouse gases and a warming climate. The other simulation is what’s known as a counterfactual world — an imaginary world in which humans are not adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, so the climate is not warming. We compare the simulations to see if the extreme we’re investigating occurs more frequently in the warmer world.

If we have all three lines of evidence, we can be confident that the event in question is connected to climate change. Essentially all heat waves fall into this category. On the other hand, we have zero lines of evidence for tornado outbreaks, so we don’t really have anything to say about how climate change is affecting those.

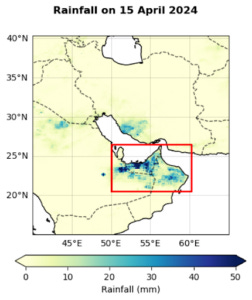

Given this, was the rainfall in Dubai in mid-April turbocharged by climate change? Luckily, the World Weather Attribution project has already weighed in. When we look for the three pillars, we find:

-

There is indeed a trend in intense precipitation in the region.

-

We have a physical understanding of why extreme precipitation gets more intense as the climate warms.

-

However, the climate models currently do not reproduce the observed trend in intense precipitation.

So we have two of three planks for confident attribution — and we all know that two out of three ain’t bad1. But it’s also not as strong as we’d like, so I conclude that we have weak-to-moderate confidence that global warming contributed to the Dubai flooding.

Attributions that come out a few days after the event are necessarily preliminary and I expect more analyses will show up in the peer-reviewed literature in the next year or two. Such analysis may increase our confidence in a climate connection, or it may not. One thing we can be confident about, though, is that it wasn’t cloud seeding.

Regardless of the outcome of this event’s attribution, rest assured that climate change is making all sorts of extreme weather events more severe.

Arguments

Arguments

Not to belabor it too much, but the relationship between climate change, the causes of climate change, and extreme weather is the same relationship as exists between a marathon runner's average running time, his use of steroids, and his best running time.

If a marathon runner's average time has been dropping over time since he began taking steroids, from 3 hours to 2 hours 50 minutes, and the next marathon he ran at 2 hours 35 minutes, or 15 minutes faster than his average. The real attribution of this change goes to his continuing steroid use, so it seems a bit wonky to attribute the fast run to his changing average.

This is what we are doing when we say that climate change CAUSED an extreme weather event. I think scientists need to be very clear when talking about causality, because linking the changing profiles of weather events to the changing average, or the changing climate, is confusing the causes with the measurements, which is not as clear as linking it to the increased amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and oceans caused by human activities, with fossil fuel use near the top. This also clarifies the difference between the nature of the current changes in the climate we are experiencing and past climate fluctuations caused by other changes in our climate system: Milankovich cycle, volcanism, etc.

Wild (may I call you Wild?):

...but if you look at that same runner's "best times of the year", and over a few years you see that "best time" is also dropping at a rate similar to the average time, then can you not link that "best time" decrease to steroid use?

Over a year, in multiple marathons, you will have other factors affecting the time. The course. Weather (temperatures, winds). Fatigue. Seasonal factors such as training schedules. When you take all that into account, and after 10 years of steroid use the runner suddenly has a "best time" that he could not have come close to before he started steroids (and his worst time of the year is better than his "best time" from 10 years ago), then isn't it safe to say he probably would not have set that "best time" without steroids?

I think the article is quite clear about this distinction. Climate scientists do usually get this right - although media articles often don't do so well.

Yes, you are precisely correct, Bob (and calling me Wild is just fine!). The point I am making in my analogy is that the "steroid" in the climate change dynamic is not climate change, it is fossil fuel use, or more generally all human activities which are contributing to increased carbon emissions that are overwhelming the system's sinks abilities to absorb it fast enough enough to keep the equilibrium in the system. It's the carbon emitting activities that causes heat retention, that result in increasingly extreme weather events, which causes climate change, and by saying that climate change CAUSED the extreme weather muddies the understanding of what triggered what and what to do about it.

Hope this helps! Attribution studies should be pointing the finger at increased carbon emissions, not climate change, at the steroids, not the changing averages, that's all.

Wild:

In the steroids analogy, one can always say "it's not the steroids, it's the training". But the use of steroids allows for faster recovery from the training, which allows more training, more strength, more endurance, etc. The path of causality is not direct. It's not simply "steroids", it's "steroids via this path..."

I think this is similar to what you are saying about climate - the root cause is not "climate change", it's fossil fuel use, which leads to X, Y, and Z.

Causality is a whole can of worms that has many nuances. Wikipedia's article seems to be quite reasonable. People arguing against climate science's position on fossil fuel-driven climate change often distort those nuances. That's an old strategy, used in the tobacco wars, the fight to reject evolution, etc.

Yes, you're correct in pointing out the multiple causal factors in a system that contribute to the performance of a system, whether it be in a marathon or the climate. This can and does contribute to distortion and manipulation by those who want to detract.

My point is that attribution should be a conversation about a variable, i.e. carbon emissions, not the measuring tool, i.e. climate change.