Sabin 33 #26 - Is wind energy good or bad for jobs?

Posted on 29 April 2025 by Ken Rice

On November 1, 2024 we announced the publication of 33 rebuttals based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in 2024. Below is the blog post version of rebuttal #26 based on Sabin's report.

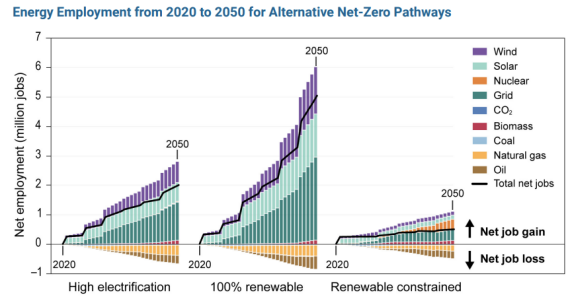

Wind power is a fast-growing industry, creating many U.S. jobs. In 2021, wind energy production employed roughly 120,000 U.S. workers, creating roughly 5,400 new jobs (up 4.7%) since 2019.1 The Department of Energy suggests that this sector could employ as many as 600,000 U.S. workers by 2050.2 As noted previously, the United States’ Fifth National Climate Assessment predicts that there will be nearly 3,000,000 new solar, wind, and transmission-related jobs by 2050 in a high electrification scenario and 6,000,000 new jobs in a 100% renewable scenario, with less than 1,000,000 fossil fuel-related jobs lost.3

Figure 1: Energy employment from 2020 to 2050 under various U.S. net-zero GHG emissions scenarios. Source: U.S. Global Change Research Program.

Most of the current domestic jobs are in manufacturing.4 Over 500 U.S. manufacturing facilities now specialize in producing components for wind power generation.5 For turbines installed in the United States, approximately 70% of tower manufacturing and 80% of nacelle assembly also occurs domestically.6 Furthermore, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics identified wind turbine service technicians as the fastest growing occupation between 2022 and 2023, growing roughly 45% in size during that time.7

Footnotes:

[1] United States Energy & Employment Report 2022, Office of Policy, Office of Energy Jobs, U.S. Department of Energy, 24 (June 2022).

[2] Wind Vision: A New Era for Wind Power in the United States, U.S. Department of Energy, 105 (2015)

[3] U.S. Global Change Research Program, Fifth National Climate Assessment at 32-31 (2023).

[4] James Hamilton et al., Careers in Wind Energy, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (Sept. 2010)

[5] Wind Energy Technologies Office, Wind Manufacturing and Supply Chain, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, U.S. Department of Energy (last visited March 25, 2024).

[6] The nacelle is the housing that holds the gearbox, generator, drivetrain, and brake assembly.

[7] Fastest Growing Occupations, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (Sept. 2023).

Skeptical Science sincerely appreciates Sabin Center's generosity in collaborating with us to make this information available as widely as possible.![]()

Arguments

Arguments

The angle here is that wind power is good because it "creates jobs".

I have to speak up on this. I have done before and I was flamed. I will try again and I expect to be flamed again.

But let me try to explain this. It will be a bit lengthy. Please bear with me.

I really like wind power. Wind power is good for a lot of reasons. But that it 'creates jobs' is not one of them.

Jobs, work, is not an asset. It's a cost.

If we could get all the goods and services we wanted without any work then the goods and services would have been free. But we can't. We pay with work to get it.

Imagine that the problem for the jobless was only that they had no work to do. Then we could solve that easily by marching all the jobbless out to a field, giving each a shovel, lining everyone up on two lines, let the first line dig a hole in the ground and take a step forward, then letting the second line fill in those holes and so on until everyone has reached the edge of the field. Then everyone turns around and starts over. This is of course totally useless. But we have 'created jobs'.

So work is a cost. If the work can produce something valuable then that value can compensate for the cost. If the product is worthless then the work is just a total loss. If the product is more valuable than the work then we have made a profit. So we should not maximize the amount of work done. We should maximize the value of goods and services produced.

A number of unemployed people is not a cost. That is an asset. Unemployed people means available work force if some need should pop up that needs work to be done.

The problem for the unemployed is not that they have no work to do. The problem they see is that they are punished for being unemployed - by getting no money. I was in that situation long ago, when I was a lot younger. I was long-time unemployed and I was punished for it and I resented that. But finally I got a job and then I was continuosly employed for 38 years. But when I did have a job, more than half of the time I was supposed to produce worthless junk. (And I did.) Some work I had to do was even not only useless but harmful. It would have been better to pay me for doing nothing. I resented that too. Now I am unemployed because I have retired and have a pension. I am very much OK with that.

So, wind power is good and it takes a certain amount of work to get it. But if we could get the same amount of wind power with less work it would be better because the wind power would be cheaper. If only half the number of new jobs was needed then the labor cost would be half. That would be good. If only a tenth the number of new jobs was needed then the labor cost would be a tenth and that would be a lot better. And if I am wrong then we might just as well get some shovels and find a field.

Now, I know that I'm just an ignorant guy, a bum with absolutely no credentials. Specifically I am not an economist. But maybe there is some economist out there who can comment.

IG @ 1:

You got "flamed"? And you expect to get "flamed" again?

No, you didn't get "flamed". You had people disagree with you. And you did not respond to any of their criticisms. Here is the comment you made four years ago (on another wind and solar energy thread).

Jobs are not a "cost" to the people that do the work. It is a source of income, which allows them to purchase goods and services. Like food, housing, clothing, etc.

Unemployed people are not an "asset" to those that are unemployed. They represent part of society that has no source of income, and cannot purchase any of the necessities of life. Unless they have savings they can dig into because they were, at some point in the past, employed. If they do not have savings, then they become a liability to society - where society either has to pay them for not working (unemployment insurance, some other form of social security payments, etc.), or has to deal with the poverty-stricken individuals that resort to crime to feed themselves or their families.

In any economic transactions, there are two sides. Money moves from one set of hands to another set of hands. Hint: banks like "debits" and dislike "credits". "Debits" are money moving from someone else's account into the bank's account. "Credits" are money moving from the bank's account into someone else's account. The bank's customer has the opposite view: credits are to the customer's favour, and debits make the customer poorer.

Reductions in labour costs usually require investments in tools, facilities, automation, etc. In Economics, these are called "capital costs". They don't come free. Businesses need to balance long-term capital costs with labour costs. Labour costs are easy to shed when business slows down. Capital costs are often called "fixed costs", because once you've paid to build a factory or buy equipment, you don't save that money by shutting the factory down. Loans still need to be paid; investors money can't go back to the investors (unless the capital items are sold). In fact, sometimes a company will continue operate a facility that is losing money because operating it loses less money than not operating it. At least the operating facility generates some revenue - even if it is not enough to cover labour+capital costs. A closed facility generates no revenue, because it produces no product to sell.

Your strawman arguments about people having jobs digging and filling holes is a red herring. There is nothing in the OP that suggests that the jobs in renewable energy will be non-productive. The fossil fuel industry is a high-capital-cost system, with relatively low ongoing labour input. That is only "efficient" if you ignore the capital costs. Renewable energy, by comparison, is low capital costs and higher labour input. That does not automagically make it economically less efficient.

IG's main point is correct: the fewer jobs per amount of energy, the better. Bob's response that reductions in labor require raising other expenses has very limited applicability currently. Perhaps it will have more applicability when robotics is applied to wind power construction and maintenance. That will be especially true when robotics is self-recycling and repairing and all electric. But by then I expect wind to be 90% obsolete, only used where there's no solar with cheap (embedded or intrinsic or standalone) energy storage.

The offshore wind industry in the US (via captured government enablers) brags about jobs: www.boem.gov/boem-announces-environmental-review-proposed-VA-wind-energy-facility-offshore At a generous 45% capacity factor that's 118 million MWh / year. At $100,000 / year for each job that's $67 per MWh. With just labor (no capital expense) the energy produced costs twice as much as solar or wind on land.

Offshore wind jobs are dangerous and grueling jobs. That's why I set a conservative $100k loaded cost per year. Women need not apply apart from a handful of strong women. The fatality rate will be similar, if not higher, than fishing: pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5958543/ This study found fatality rates in fishing fleets during 2010–2014 ranging from 21 to 147 deaths per 100,000 FTEs, many times higher than the rate for all US workers.

The labor productivity will be low due to many factors: remoteness of work, storm delays, coordination delays where workers will have nothing to do. The numbers given in my first link may have originated here: www2.nrel.gov/wind/offshore-workforce in which case a portion of the jobs are on land, less dangerous, more productive or co-productive.

But my point stands: offshore wind as a jobs program is ludicrous. I am fighting against offshore wind here in Virginia as much as I possibly can, since as a co-owner of Old Dominion (because of where I reside) I will pay for it.

Ignorant Guy,

I am not an economist. But I have training and experience that helps me understand economic matters. I am a Professional Engineer with an MBA who has decades of experience with major construction projects.

Bob Loblaw has provided a good response to your comment @1.

I would add the following:

Regarding Ignorant guys and Erics comments. The fact that it would be great if nobody had to work and everything was done by robots doesn't change the fact that creating jobs is a good thing right now. Right now we have millions of guys going through the education system all on the expectation of getting a job. If they dont they will be dependent on social welfare or charity. So anything that creates jobs is a good thing, at least in the medium term until robots are prolific. And assuming the jobs add genuine value like renewable energy.

Personally I think the idea we will eliminate all work and have literally everything done by robots is a pie in the sky fantasy, because its unlikely the world has enough resources, especially the rare earth metals for example. They are not rare but they are certainly not prolific either in a way that can actually be mined. But time will tell and it looks like the economy will do its best to automate everything. Its an unstoppable ship in that regard.

Sure I agree offshore windfarms are not ideal in various respects, but they are a response to concerns about visual impacts of onshore windfarms and land use issues so there is that bigger picture to consider. I think the concerns about onshore windfarms are over stated but its a case of trying to keep everyone happy.

Eric @ 3:

You think that IG's main point is "the fewer jobs, the better"?

Let's take his example of a crew of workers with shovels divided into two groups - one group digging holes, the other group filling them back in. Maybe the previous week there were three groups of workers. Some efficiency expert (let's call him "Elon") decided that was too many workers, so they fired one of the three groups. That group turned out to be the group that was responsible for planting the trees in the holes before they got filled back in. No, they haven't made the process "more efficient" - they have destroyed it.

Granted, IG did word things later in his comment "...if we could get the same amount of wind power with less work...", but that completely ignores the capital costs, as I pointed out in comment 2.

Let's take another example. I recently had some electrical work done, by an independent contractor who worked alone. Yes, he could have pulled the cable by himself, by repeatedly walking back and forth between the basement and the garage, but I was able to help him. That made the job go much, much faster, even though it now meant that there were two people working on the job. More people actually reduced the labour input in total, because it eliminated the "useless" work of walking back and forth between the basement and the garage,

The point is that trivial, simplistic views of "job counts" and "labour costs" are pretty much going to steer you wrong if you are not careful. Especially when they ignore other costs (e.g. capital). Maintenance has been mentioned. Some companies (and governments) consider that to be an optional activity. Easy to cut when money is tight. We'll make things "more efficient"! Until lack of maintenance leads to equipment failures - or roads falling apart, or bridges collapsing - which ends up costing much more in the long run. Short term gain for long term pain.

You (Eric) say that "...raising other expenses has very limited applicability currently". Wind turbines and solar panels don't make themselves, and they cost money. You mention robotics. They don't make themselves. Even if they eventually do, there are still materials needed, and those will cost money - even if they, too, are mined and refined using robotics.

As OPOF points out, this blog post is a rebuttal to the "wind and solar destroy far more jobs than they create" myth. The myth makers introduced the metric. They need to live or die on that hill.

You can then start to argue about the quality of the jobs. You can then start to argue about the general economic and society impacts of different approaches. Which is better: everyone has a job with a moderate income, or 10% of the people have an extremely high-paying job and 90% have nothing? Does your answer to that depend on whether or not you are part of the 10%?

If automation is the solution, are you familiar with how automation has affected the people and communities that have lost jobs in the coal industry? You might want to read the SkS repost of "How to sell solar in coal country" from a year-and-a-half ago.

Bob, I was trying to simplify IG's point to reinforce my point which is something I have previously commented on. In a nutshell: productivity matters in energy production.

Your second example (pulling cable) is an example of productivity maximization that you figured out. Installing and connecting offshore wind is a complex endeavour that has to be timed (choreographed) to avoid men waiting for other men to do something or traveling around to different locations. Storms can completely interrupt work. Dangerous procedures cannot be rushed in any way. These are all drags on productivity.

The capital costs that you refer to are independent of automation that I now regret bringing up. My point was that offshore wind is extremely labor intensive, but that will be inevitably alleviated by automation. I agree capital costs are rather high too but we can't lower labor costs by spending more on capital.

You can argue that extra employment has large societal benefits in the case of solar because the upfront employment pays off over many years with very reduced labor. I don't believe that's true for offshore wind from what I read.

I'm sorry I started the argument about automation which led to the issue of even income distribution as an argument for offshore wind.

Skeptical Science asks that you review the comments policy. Thank you.

I am an accountant working in a manufacturing environment. Electric generation is one of many manufacturing processes. I also have a minor in economics.

Several points that others have touched on, yet those who have have commented have shown a superficial understanding which should be clarified, (my apologies for any appearance of negativity to other commentators.)

A) Under every economic theory, labor is a cost , just the same as capital is a cost. Attempts to claim that Jobs / labor is not a cost is simply inane. Further attempts to justify increased labor as a reduction in costs is not relevant. B) With rare exceptions and then only for short term periods, higher labor costs and/or higher number of jobs per units of production are classic signs of less economic efficiency, not greater efficiency.

While the op is whether more jobs are gained than lost, the more important question is whether total costs are increased or decreased.

David-acct @8 :

You are in a narrow sense perfectly correct, in stating that :-

"... higher labor costs and/or higher number of jobs per units of production are classic signs of less economic efficiency, not greater efficiency.

While the op is whether more jobs are gained than lost, the more important question is whether total costs are increased or decreased." [unquote]

Nevertheless, you make a circular argument.

The weasel word is cost. Cost in dollars is one thing, and yet overall cost is another. More importantly, overall cost (long term cost) is best measured by the health & stability of society ~ the Common Good (as per Adam Smith).

While I would not advocate for a return to the un-mechanized Age of Adam Smith, where (by necessity) more than half the village went out to bring in the annual harvest ~ still, the harvest work was in one sense a "good" for the village community, in fostering mutual respect & comradeship / healthy feeling of togetherness. # Despite any "economic" or dollar-cost inefficiency.

One danger nowadays, is the rapid movement towards even greater dollar-cost efficiency, through the use of Artificial Intelligence. Less cost, but more unemployment. But how to find a healthy societal balance?

( For myself, I would prefer to pay the extra dollars, to have real flesh-and-blood actors in a movie or advertisement; and real human actors reading the voice-overs in other productions of podcasts & documentaries, etc. Wouldn't you? ~Or would you prefer an AI-generated Prince Hamlet image ? )

Anecdote : the AI "readers" can be anodyne and/or irritating . . . and yet sometimes sourly amusing in their bloopers. # My recent favorite was an AI repeatedly reading the text of the religious "St. Catherine" as "Street Catherine". (It seems there is no soul or ghost in the machine ! )

David-acct

"A) Under every economic theory, labor is a cost , just the same as capital is a cost. "

Correct. Good to be reminded of basic accounting, not my area of expertise that's for sure.

"Attempts to claim that Jobs / labor is not a cost is simply inane."

Nobody here has claimed that jobs are not a cost. BL said "Jobs are not a "cost" to the people that do the work. It is a source of income, which allows them to purchase goods and services. Like food, housing, clothing, etc." Emphasis mine.

"While the op is whether more jobs are gained than lost, the more important question is whether total costs are increased or decreased. "

Total costs of wind and solar power seem to be decreased compared to coal fired power. Wind power and solar power appear to now be cheaper than coal power using the Lazard Energy Analysis. Total costs using such analysis are a function of capital +labour + running costs. Although renewables have higher labour costs than coal and possibly higher capital costs they have a big advantage in low running costs that gives them an edge.

But such an analysis is narrow. There are the other costs to consider such as health and stability of society that Eclectic mentions Eclectic is right that renewables job creation while reducing efficiency in certain cases by requiring more labour than the alternatives, can add other benefits. The health costs of renewables are considerably lower than with burning coal with its nasty particulate emissions. Studies attest to this. Then there are the environmental costs of renewables are considerably lower overall than coal because it reduces the global warming problem. Add all this into the equation and total costs of renewables are considerably less than costs of burning coal. I know there are other minor factors and renewables do have some downsides but renewables look very cost effective in the wider sense of the term.

Eric @ 7:

Your clarification makes sense, although I would argue that automation and capital costs go hand in hand. Any system that provides tools and equipment that reduce labour input will have costs associated with that equipment. That applies at the simple level - replacing a hand drill or screwdriver with a powered one - or at a more complex level - replacing several factory workers with a robotic assembly line. "Automation" is a rather loose term (and IG used the term in his post from 2021, which he alluded to in his first post here.)

When it comes to "job creation", you correctly allude to (without explicitly stating it) the duality of jobs constructing or installing the system vs. jobs required to keep it running. Labour in building a nuclear plant or wind turbines, or installing solar panels on a roof, will be considered "capital costs". Keeping it running will fall under "operations and maintenance".

Large up-front capital costs are typically amortized over a period of time. Most easily illustrated if you had to take out a loan to get the money, and pay it off over a number of years. But even if you have all the money on hand at the start, accounting rules (either what your accountant suggests, or what the tax system allows) will dictate that the cost be spread out over time. This will often be related to how quickly that asset depreciates (e.g., the electric drill wears out, or the nuclear power plant ceases to work without a major rebuild).

If most of the "created jobs" are "temporary" jobs related to manufacturing or construction, then you need to keep making more in order to provide long-term employment. One prominent local politician once promised to create 800,000 jobs in his job-creation plans. It turns out that he was counting 100,000 "new" jobs that would last for 8 years as "800,000 jobs". Or maybe he was thinking those 100,000 jobs created in year one only lasted one year, and he'd create 100,000 more new jobs last would last one year in year two, etc. If so, taking credit for creating 800,000 jobs over 8 years while ignoring the 700,000 people that lost their jobs after one year seems a little rich. Details matter.

David-acct @ 8:

You say "Under every economic theory, labor is a cost...". I'd disagree with nigelj @ 10 and say that you are only half-right. As I pointed out in comment 2 (which nigelj mentions in #10), every financial or economic transaction has two sides. One will consider labour to be a cost, and the other will consider that transaction to be a financial gain. To the worker, their labour is a product that they are selling, not buying.

I challenge you to point to the post and wording that you have characterized as a "...claim that Jobs / labor is not a cost..." or ..."to justify increased labor as a reduction in costs...".

With your extensive accounting background, I am sure that you are familiar with Double-entry bookkeeping. To those that are not familiar with it, the Wikipedia entry I link to says this:

This double-entry principle can be applied on the level of a single corporate (or home budget) level, but it applies even more when you look at basic economics and the economy as a whole. For every employer, there will be one or more employees. For every purchaser of a good or service, where the transaction is a cost, there will be a seller, where the same transaction is income.

You (David-acct) also state "...labor is a cost , just the same as capital is a cost." And then you completely ignore capital costs when you state "...higher labor costs and/or higher number of jobs per units of production are classic signs of less economic efficiency, not greater efficiency." This is wrong. Higher labour costs would be associated with less labour efficiency". Just as higher capital costs would be associated with less capital efficiency. Economic efficiency requires looking at both labour and capital costs.

Please don't counter what you call "superficial understanding" with your own superficial explanation.

Eclectic @ 9:

You mention "overall cost". The phrase that comes to mind is "that person knows the cost of everything, but the value of nothing". The economic system that looks solely at the $ involved, misses out on the value of what is "good" for the community. The environment often gets the short straw on this.

This is particularly true when a small portion of the economy (e.g., energy production) finds a way to avoid the costs of something internally (i.e., "we don't have to pay for it"), but the costs still exist externally (increasing weaher disasters, polluted water, etc.). Externalities are a well-known part of economic theory. Privatized profit, and socialized costs.

A trivial example of the weakness of economic accounting involves two people that car-pool to work. Person A drives one week, and person B drives the other week.

Bob, thanks for your reply in #11. I agree automation can boil down to increasing capital expenditures to reduce labor costs. Automation might be coming down in cost but certainly not cheap yet.

I also agree with your point about installation versus O&M. Some renewables have very low O&M cost since the fuel is free and the equipment (e.g. photovoltaic) has no mechanical wear. But I believe any time we do things offshore, the O&M costs such as wear and tear will increase along with labor costs.

Eric @ 14:

Any offshore project involves different, and often more difficult, conditions and operation.

One major Canadian oil field is the offshore Hibernia field, east of Newfoundland. Considerable difficulties from the beginning, including exploration, drilling, and production. During drilling, a semi-submersible rig named the Ocean Ranger was lost during a storm in 1982, with 84 lives lost. The oil field came into production in 1997. The Hibernia production platforms are serviced by helicopters. Mechanical failure on one flight in 2007 resulted in the loss of 17 lives.

Even the "benign" offshore environment of the Gulf of Mexico has its issues. They have figured out how to deal with hurricanes, but the Deepwater Horizon oil spill demonstrated the difficulties of dealing with problems in an offshore environment.

You don't even have to go offshore to get more difficult working environments. I spent several years working in the area of permafrost and pipeline design in the north. The Trans-Alaska oil pipline was a much more difficult planning, construction, and operating task than pipelines in more hospitable environments. For natural gas, there have been a couple of proposals for pipelines to bring the Beaufort Sea gas reserves to the south: the Alaska Highway route, and the Mackenzie Valley route. Neither has been constructed, in large part because of the expense and technical difficulties. (I worked on both of these. I don't think that explains why they failed, though.)

To try to get back to the OP, which deals with job creation in a very general sense, it is clear that different projects, in different working environments, will have different work skills and requirements at all stages of exploration, planning, design, construction, and operation. Just counting "jobs" is a very simplified view of things. The devil is in the details. Once more, the myth that is being rebutted is the "wind and solar destroy far more jobs than they ever create" argument. The OP does that.

One can then argue about the quality of jobs, etc. But positions taken in that argument will probably depend on whose ox gets gored.

One follow-up to my comment #12, talking about costs. Economic theory includes the concept of opportunity cost. This is a hidden cost, that will not show up on the accounting statements. To quote the Wikipedia link I gave,

The "cost" need not be financial, but it is easiest to illustrate using a financial example. If I decide to invest $1000 in a GIC that returns 2% for a year, simple accounting says "great! I'm up $200 by the end of the year!" But if I also had an opportunity to put $1000 into a bond that returned 4%, that investment would have returned $400 at the end of the year. Making the choice to buy the GIC has cost me $200.

The choice between capital costs and labour costs, discussed in several comments here, is an obvious example where "opportunity cost" is relevant. Eclectic's comment 9 and nigelj's comment 10 touch on more intangible costs at a society level. From a society viewpoint, there are "opportunity costs" involved in choices to follow one path or another (e.g., renewables vs. fossil fuels).

There is another economic consideration regarding the pros and cons of the transition from unsustainable harmful fossil fuel energy systems to more renewable, more sustainable, systems. Note that to be sustainable the renewable systems need to be understandably less harmful than the system they are replacing.

The ‘costs’ should not govern the decision making. The costs of the diversity of ways to achieve the transition would matter when choosing the corrective actions. But the transition has to happen to limit the costs of the harm done. The transition does not have to be ‘more profitable or less expensive’. Doing things less harmfully and more sustainably are likely to be more expensive or harder work than developed less sustainable activities.

It is important to understand that, depending on the perspective of interest:

Another way of saying this is that a system that is already in motion may need correction to develop more sustainable, improved, conditions. Learning about harms being done and risks of harm is the only way to develop helpful corrections. But making corrections in ways that minimize disruptions to the developed system may be so slow that significant harmful results will be produced before the system is significantly corrected to be more sustainable.

An example of this understanding would be a large ship that requires a course correction to avoid an increasingly harmful situation. By the time the harmful situation the ship is headed towards is well understood the required course correction may cause some things on the ship to move around and potentially be damaged (costs of the correction). Delaying the course correction, because of a desire to avoid disruptive costs, will likely develop the need for more disruptive, more costly, course correction. And too much delay in the course correction, or a correction that is too gradual, can result in serious damage to the total system.

The desire to limit harm to elements in an operating system can delay correction to the point of creating a situation where even the most disruptive possible correction will not avoid damage to the overall system.

Trying to protect elements of the developed system can result in a failure to avoid future harmful circumstance that damage the overall system.

Elements within the system will have had their ‘disruptions’ limited ... to the detriment of all parts of the system.

Very harmful leadership action would be ‘protecting developed undeniably harmful interests’ by undoing corrective harm reduction and avoidance actions.