Deep emissions cuts this decade could prevent ‘abrupt ecological collapse’

Posted on 10 April 2020 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Carbon Brief by Daisy Dunne

Swift global action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions could prevent the “abrupt” collapse of ecosystems, which may otherwise begin within the next few decades, a study finds.

The research, published in Nature, finds that uncontrolled climate change would see tropical ocean ecosystems exposed to potentially catastrophic temperature rise by 2030. By 2050, tropical forests could also face such conditions.

By comparison, limiting global warming to below 2C – the goal of the Paris Agreement – could delay the date of exposure by up to six decades, according to the research.

The results “show very clearly that it is not too late to act and the benefits of acting now will be massive”, a study author tells Carbon Brief.

Burning up

Rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns are expected to make existing habitats inhospitable for many animal species. Due to this, some scientists expect that climate change will overtake land-use change to become the largest threat facing wildlife by the end of the century.

However, it is not yet certain at what point this century the effects of climate change will begin to overwhelm ecosystems. The new study addresses this question by looking at when various land and ocean ecosystems are likely to be exposed to possibly intolerable increases in temperature.

The results suggest the fate of ecosystems could hinge on the world taking immediate action to tackle climate change, says study author Dr Alex Pigot, a research scientist at the Centre for Biodiversity and Environment Research at University College London. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Our results show that with continued high emissions of greenhouse gasses, losses of biodiversity and disruption of ecosystems from climate change are likely to happen abruptly and could occur much sooner than we had expected.

“According to our models, biodiversity losses are likely to be already underway in the tropical oceans and over the next few decades these risks are expected to escalate rapidly, spreading to tropical forests and then higher latitudes by 2050.”

Corals to forests

For their research, the authors estimated the first date at which species in different world regions are likely to face temperatures beyond what they are known to tolerate in the wild.

Exposure to such temperatures could cause species to die out in that region – or to go “locally extinct”. However, it is possible that some species could adapt to intolerable temperatures, Pigot says:

“It is important to note exposure does not necessarily mean extinction. Some species may be able to persist at temperatures warmer than those under which they have previously been found, but this is not something we should blindly assume. Indeed, for some species we already have very good evidence that their current [temperature range] is likely to correspond closely to their physiological limits.”

They did this for more than 30,000 species spanning the world’s habitats, from tropical coral reefs to highland pine forests.

Western lowland gorillas and forest elephants in a clearing in tropical rainforest, Obandas Bai, Repubic of Congo. Credit: Nature Picture Library / Alamy Stock Photo

Western lowland gorillas and forest elephants in a clearing in tropical rainforest, Obandas Bai, Repubic of Congo. Credit: Nature Picture Library / Alamy Stock Photo

It should also be noted, however, that the authors only studied changes to temperature and rainfall exposure. They did not model other climate-change impacts known to affect wildlife, such as heatwaves or the disappearance of Arctic sea ice.

The authors looked at the timing of exposure under several scenarios for future climate change, known as the “Representative Concentration Pathways” (RCPs). These scenarios include one where future greenhouse gas emissions are very high (RCP8.5) and one where temperatures are limited to below 2C (RCP2.6). (It is important to note that RCP8.5 is not a “business as usual” scenario, but rather a scenario where no policies are put in place to tackle climate change.)

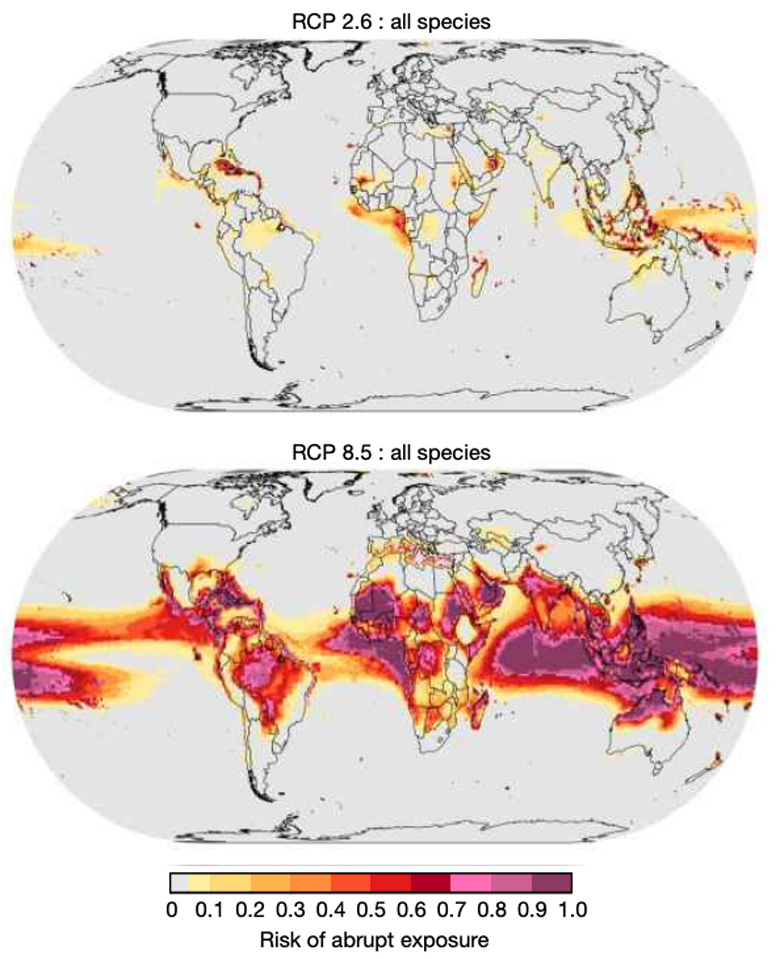

The two maps below illustrate how the risk to wildlife differs in these two scenarios. The maps show the risk of an ecosystem seeing an “abrupt exposure event” under RCP2.6 (top) and RCP8.5 (bottom). An “abrupt exposure event” is defined as when more than 20% of all species in an ecosystem are exposed to temperatures beyond their natural range in a single decade.

Risk of abrupt exposure of ecosystems to intolerable temperatures under RCP2.6 (top) and RCP8.5 (bottom). Risk is defined as the proportion of the 22 climate models used in the study that expect a given region to experience an abrupt exposure event by the end of the century. For example, a risk of 1.0 (dark purple) indicates that all the models expect that region to see an abrupt exposure event by the end of the century, while 0.0 (grey) indicates that none of the models expect there to be an exposure event. Source: Trisos et al. (2020)

The maps show how, under high emissions, many biodiversity hotspots, including the Amazon, parts of southern Africa and southeast Asia, could face a very high risk of exposure to intolerable temperatures by the end of the century.

The research finds that, under 2C of global warming, only 2% of ecosystems worldwide are likely to face an abrupt exposure event by the end of the century. Under 4C, this proportion rises to 15%.

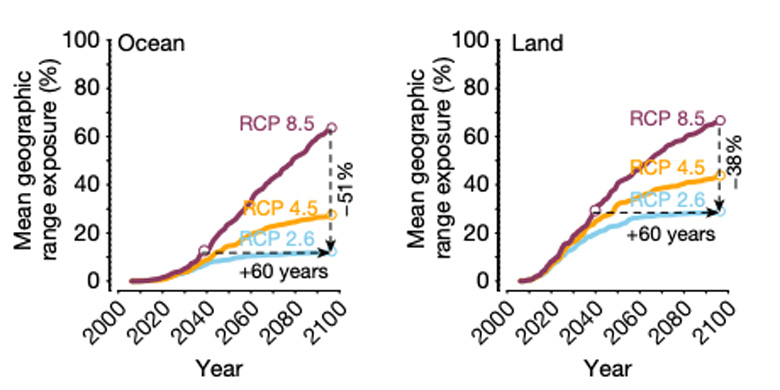

The authors also find that limiting global warming to below 2C could delay the time when ecosystems first experience abrupt exposure events by up to six decades, when compared to the RCP8.5 scenario of very high emissions

This is indicated on the charts below, which show the projected percentage of the world’s ocean (left) and land (ecosystems) exposed to intolerable temperatures under RCP2.6 (light blue) and RCP8.5 (purple) from 2020-2100. (The chart also shows results for RCP4.5 (orange), a scenario where future emissions are moderately high.)

The projected percentage of ocean (left) and land (ecosystems) exposed to intolerable temperatures under RCP2.6 (light blue), RCP4.5 (orange) and RCP8.5 (purple) from 2020-2100. Source: Trisos et al. (2020)

‘Not too late’

The research finds that, under a very high emissions scenario, ecosystems could be exposed to intolerably high temperatures as early as this decade. However, this does not mean it is too late to act, Pigot tells Carbon Brief:

“Our results show very clearly that it is not too late to act and the benefits of acting now will be massive and will accumulate over time. By holding warming below 2C, we can effectively ‘flatten the curve’ of how climate risks to biodiversity accumulates over time, delaying the exposure of the most at-risk species by many decades and averting exposure entirely for many thousands of species.”

The findings are “very strong and convincing” says Peter Soroye, a PhD candidate in biology from the University of Ottawa, Canada, who recently published a study on projected bumblebee declines worldwide. He tells Carbon Brief:

“One of the critical things that this and other large-scale studies on climate change-related biodiversity impacts show is the positive effect of reducing carbon emissions on future biodiversity. Work like this demonstrates that while future climate change will modify ecosystems around the globe – overwhelmingly for the worse – we can mitigate many of these impacts by rapidly reducing our carbon emissions.”

Trisos, C. H. et al. (2020) The projected timing of abrupt ecological disruption from climate change, Nature, doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2189-9

Arguments

Arguments

The results of this study suggest that fast action will help a lot compared to BAU. That is good news.

Last August I was able to log a few SCUBA dives on the North side of Cuba and at Cozumel. These are reputed to be among the best dive locations in the world. In both locations over 90% of the coral was dead. In Cozumel they closed the main wall to diving in hopes it would recover. The surrounding areas were very dead. There was also little fish life considering that Cozumel banned all fishing decades ago.

It was recently reported in the Smithsonian Magazine that the Great Barrier Reef is facing its most widespread bleaching event ever, the third in 5 years.

Perhaps coral reefs are the first to go and other locations will not be as bad. I noticed that North Cuba and Cozumel are in the few areas hit hard in the RCP 2.6 graph in the OP.