Scientists examine threats to food security if we meet the Paris climate targets

Posted on 3 April 2018 by John Abraham

We have delayed action for so long on handling climate change, we now can no longer can “will it happen?” Rather we have to ask “how bad will it be?” and “what can be done about it?” As our society thinks about what we should do to reduce our carbon pollution and the consequences of electing science-denying politicians, scientists are actively studying the pros and cons of various emission reductions.

Readers of this column have certainly heard about temperature targets such as 1.5°C or 2°C. These targets refer to allowable temperature increases over pre-industrial temperatures. If humans take action to hit a 1.5°C target, it means we are committed to keeping the human-caused global temperature rise to 1.5°C. Similarly for a 2°C target.

The lower the target, the smaller the climate change. The smaller the climate change, the better. But is it worth the effort to set lower targets? I mean, if 2°C is good enough, why take the trouble to keep temperatures within 1.5°C?

Fortunately, a new paper just out in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A asks this question. Specifically, they ask “How much larger are the impacts at 2°C compared to 1.5°C?” A follow-on question asked by the authors relates to what conditions occur at a particular level of warming, such as 2°C. This is a really important question because policymakers need to know what it will take to adapt to a 1.5°C world or a 2°C world.

The authors focus on the impact of climate change on food security, and in particular, how changes to extreme weather will impact food production. The weather issues that are central to this study are drought and precipitation. We know that in a warming world, the weather will get wetter. This is because warm air is more able to hold water (air can be more humid). As a consequence, when rains fall, they come in heavier bursts. We are already seeing this in the US, for example, where the most extreme rainfalls are increasing across the country.

So, there are competing issues and an obvious question is, which will win out? Will the world become drier or wetter? The answer to this question depends on where you live. It is likely that areas that are currently wet will become wetter. Areas that are currently dry will become drier. This is just a general rule of thumb, there are variations to this rule. But it is a pretty good generalization.

This behavior is vexing for farmers because it makes planning for the future complicated. But this study at least shines some light on the subject and helps us prepare. To complete the study, the authors considered an Earth that has 1.5°C warming and another Earth with 2°C warming. The authors then identified specific measures for extreme weather. Among the measures are the annual maximum temperature, the percentage of days with extreme daily temperatures, the number of consecutive dry days, and the maximum rainfall in a 5-day period.

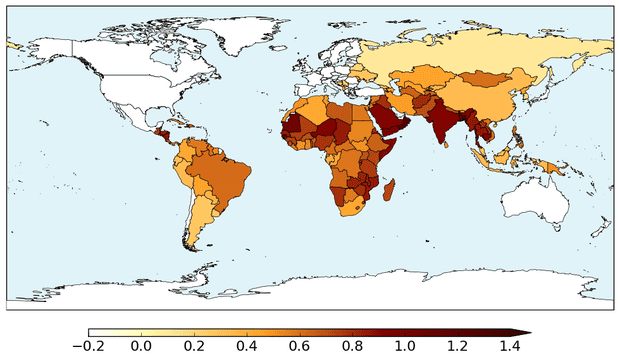

Measures of heavy rainfall and drought were combined with societal factors to form a Hunger and Climate Vulnerability Index. The index incorporates how exposed a country is to climate hazards, how sensitive a country’s agriculture is to climate hazards, and how able a country is to adapt. With these metrics and indices calculated for 122 countries in the developing and under-developed parts of the globe, the authors show that some areas will be more impacted than others.

Increased wetness will affect Asia more than other regions. Among their predictions is that the water flowrate in the Ganges river may increase by 100%. However, increases to drought could hit Africa and South America hardest. An example outcome is that the Amazon river flow may decrease by 25%. They also found that for most of the planet, a 2°C world is worse than a 1.5°C world. This is to be expected, but now there is a way to quantify the impact of incremental increases in temperature on societal impact.

When the authors continued their look at various regions, that found that temperature changes are amplified in some locations. For instance, with a 2°C warmer world, the land areas mostly warm by more than 2°C. In some regions, like North America, China, northern Asia, northern South America, and Europe, the daily high temperature increases could be double that of the globe on average.

In the figure below, the Hunger and Climate Variability Index is shown for a 2°C warmer world. The image is scaled according to how vulnerable they are to food insecurity. Countries with a larger value are more vulnerable than countries with a smaller number. Any country with a vulnerability greater than 1 is more vulnerable than any country today.

Hunger and Climate Vulnerability Index for 2°C global warming. Illustration: Betts et al. (2018), Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A

As lead author Richard Betts explained,

Arguments

Arguments

Please fix the first sentence: "now can no longer can"?

Interesting map – but no surprises. Countries of Europe, North America and Australasia have no reason to feel complacent. It is likely that most will be affected by sea level rise reducing fertile coastal land now producing food crops and destroying infrastructure essential for its distribution.

The article asks: ‘is there a tipping point for ice sheet loss from Greenland or Antarctica? A certain temperature threshold that once passed cannot be reversed?’ I would have thought the answer was indicated by Arctic amplification, sea ice depletion and increasing mass loss from polar ice sheets.

Is it likely that these indicators are going to reverse?

It mystifies me why Australia is not particularly at risk. This country has a considerable history of droughts already.

Policy makers should already understand what needs to be corrected and why, or at least they can't claim that the required information was not available yet.

The Sustainable Development Goals were published in 2015. The fundamental understanding of what is wrong and needs to be corrected was pretty clear in the 1972 Stockholm Conference. It has been reinforced by every subsequent increased understanding, especially in the 1987 UN report “Our Common Future” and the 2012 UN report “Back to Our Common Future”.

The reasons for the resistance to the understood corrections is also well understood. Naomi Klein's “No is not Enough” is one of many presentations of understanding regarding the developed Private Interests that are harmful to achieving the sustainably better future for humanity.

The obvious losers of climate change impacts are the entire future generations that have to 'adapt to the rapidly changed climate' (even the biggest winners among them will suffer to a degree), thta is created by the lack of responsible correction/restriction of behaviour of the richest and most influential in the previous generations.

The trouble-makers identified by the likes of Klein try to claim it is reasonable to do unsustainable things and create costs and challenges for others, especially future generations. They like to compare the perceived benefit or opportunity that they have to give up if creating those impacts on Others was rapidly curtailed (careful not to point out that it is mainly the sub-set of trouble-makers who would have to give things up), to the current generation's perceptions (the trouble-makers claimed perception) of the created future costs or challenges.

In engineering design the future risk of negative consequences is to be minimized to make the built item a sustainable benefit rather than a future problem or burden. Creating problems others have to deal with in the future is understood to be unacceptable. When uncertainty is involved, the potential for negative future consequences is conservatively mitigated by over-estimating the impact and under-estimating the ability of what is built to adequately deal with those impacts.

However, in some business thinking, the future risks of negative results are often considered to be mitigated by having someone else suffer the negative consequences, or gambling that the ones benefiting in the near term will not be penalized by any negative result that occurs in the longer term.

Clearly policy makers need to follow the engineering approach (the application of science approach), not the business approach (the gambling to get rich quick approach). Don't get me wrong. A policy maker with business experience could be a very effective applier of science through the engineering approach. The key is to be willing to identify and effectively address the other types if they should get away with temporarily Winning anywhere.

Focusing on properly identifying who deserves recognition and reward and who deserves to be disappointed and discouraged is what all policy makers understand they need to develop, but some of them are motivated by other Private Interests.

Those other Private Interests are not interested in minimizing the negative impacts on future generations. Regarding food production, they would not like to see the development of responsible limits to long distance transportation of food. They would not like local agricultural Coops developed to maximize the local benefit of what can be locally grown for local consumption (rather than multinational investor operations). They would also not like to see trade limited to emergency food aid and the importing of produce that cannot responsibly be grown locally in an area (but still obtained with limited transportation).

Working towards those types of corrections do not need improved understanding of the regional level of climate change impact. Those corrections are required, along with the requirement to most rapidly reduce the impacts causing increased climate change challenges.

nigelj@3,

Food exporting places like Australia would not be considered to be at risk because they can 'reduce how much they export'.