The Future for Australian Coal

Posted on 16 April 2019 by Riduna

Problems

Australia is the worlds’ largest exporter of coal, selling thermal coal for electricity generation and coking coal for smelting world-wide. In 2017 its export of this commodity was valued at over $40 billion, most of it produced in Queensland and New South Wales. In addition, coal is mined for domestic use with about 42.3 million tonnes,valued at over $4 billion being consumed in 2017, primarily for generating electricity.

Federal and State governments make important financial gains from this through collection of royalties and income tax on coal production and sale. These gains enable governments to provide quality essential services which assist in maintaining a high standard of living for all Australians and sustain rural towns with steady employment provided directly by mining operations and related industries dependent on them.

However, a problem with coal is that its mining involves emission of methane and Australia has 21 coal mines currently in operation. The volume of methane emitted by them is not accurately known nor is it known if those emissions are included in official estimates of national emissions. A more serious problem is that when burnt, coal produces carbon dioxide (CO2) and is estimated to be responsible for 30% of all CO2 emissions in Australia – and world wide.

As such, coal production and combustion are major contributors to global warming and its effects on climate which in recent years have been marked by increases in the frequency and severity of weather events world-wide. These increases have prompted growing public protests, particularly by younger people and calls for governments to be more active in planning and acting to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

Fig 1. Dead fish floating on the Darling River at Menindee, 2019. Rivers stopped flowing. Over 1,000,000 fish died from hypoxia. Picture: Robert Gregory/AFP.

Fig 2. Livestock losses due to drowning in the 2019 North Queensland floods and subsequent starvation estimated at 500,000 head. Source: The Guardian.

In Australia, damage caused by severe weather events in 2019 has included prolonged drought and fires, floods and heatwaves producing record high temperatures and extending summer temperatures by 5-6 weeks. Their effect has seen massive loss of habitat and wildlife, huge losses of property and livestock which will take 3-5 years to replace – provided there is no repeat of the destructive events causing them. Recovery from the damage caused by 2018 events is estimated to cost $18 billion.

Major users of coal to generate energy, particularly China and India have found that, apart from greenhouse gas emissions, coal combustion results in high levels of particulates which cause visible air pollution (smog) endangering public health and contributing to premature deaths. Another by-product of burning coal in power stations is the generation of massive volumes of ash, often stored in areas where it can leach into waterways making them unpotable and contaminating fish, making their consumption dangerous to health.

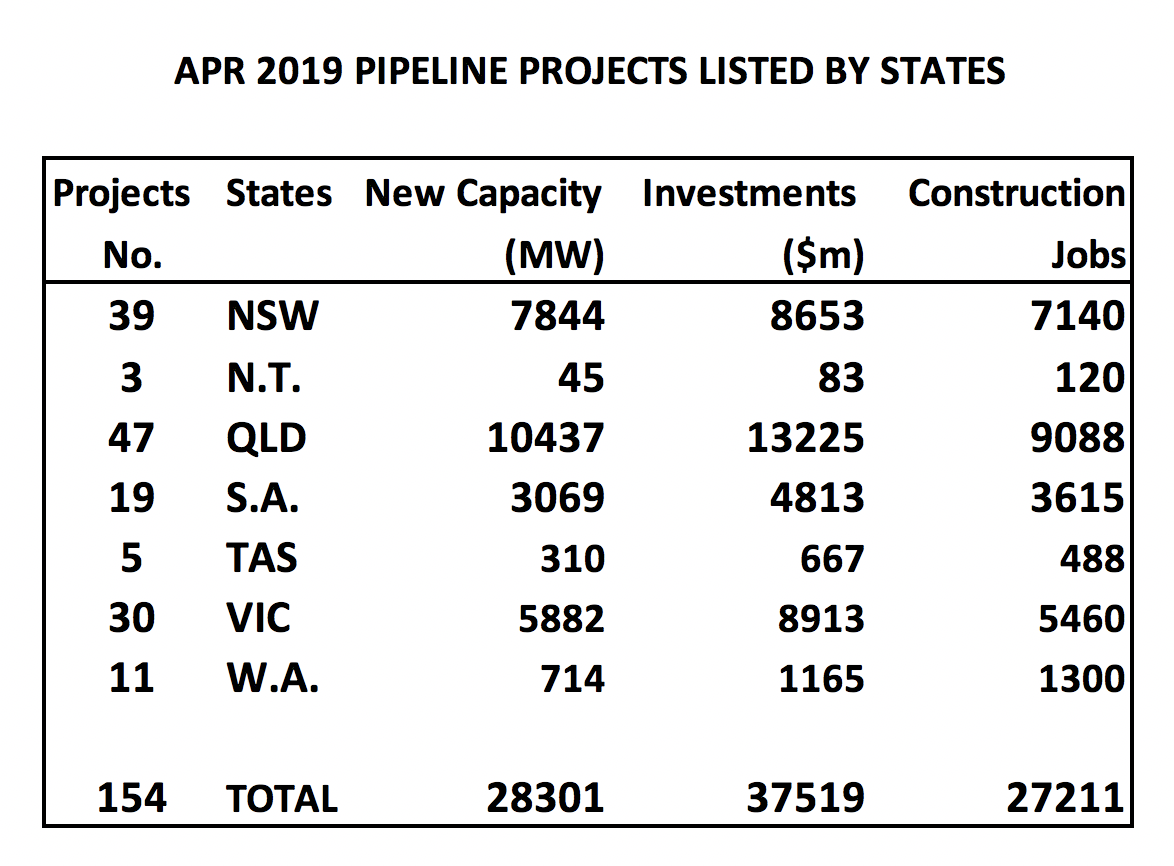

Fig 3. Renewable energy projects approved to be built and commissioned in Australia over the next 3 years. Over 50 projects are likely to complete in 2019. Note: This Table excludes major proposals such as Snowy 2.0 (energy storage) and the Pilbara Power Hub (9 GW for export) which are not yet ‘shovel ready’. Source: Authors research and Clean Energy Council data.

Demand for Australian coal for domestic use is declining as the nation transits to renewable energy. As shown above, $37.5 billion is expected to be invested in electricity storage, solar farms and wind turbines over the next 3-5 years. Australia is not the only country moving away from coal to renewable energy sources. Many countries are replacing coal with gas because it is cheaper. It also has lower greenhouse gas emissions when burnt.

If undertakings by countries subscribing to the Paris Accord are to be met it is inevitable that global coal-fired electricity generation must decline. This will be accompanied by transition to renewable energy sources, primarily wind and solar. China, the worlds’ largest user and second largest importer of coal, has announced that its import and use of seaborne coal will fall - a trend likely to continue in coming years. Countries, such as The Netherlands, Italy, Germany and others could stop using imported coal by 2030 or sooner, resulting in continuous decline in global demand from 2020 until its use ceases completely by 2050.

Given this scenario, it came as no surprise that in 2017/18 Rio Tinto sold all of its coal mining assets in Australia or that more recently, Australia’s largest coal mine operator, Glencore, should decide to cap its global coal productionat present levels. That decision was taken partly in response to concerns over the effects of burning coal on the environment and achieving Paris Accord targets. What did come as a surprise was the New South Wales Land and Environment Court decision to refuse an application to develop a new coal mine on the grounds that it would contribute to climate change.

These developments have thoroughly alarmed right-wing, climate science denying members of Australia’s Coalition Government, particularly those from the National Party. They have been vocal in calling for a new coal-fired power station to be built in Queensland to ensure supply of cheaper electricity 24/7, to increase domestic use of coal and protect coal mining jobs. The implication being that massive job losses and blackouts will occur damaging the economy unless such action is taken.

The Prime Minister and Liberal Party Leader who faces a General Election in May 2019, has ruled out the proposal, correctly noting that the Queensland Labor Government would never give approval for a new coal-fired power station. To placate pro-coal, right wing members of his own Party, government invited expressions of interest in receiving public subsidies for the cost of continuously supplied electricity.

The need to offer public subsidies arises from the fact that banks and other lending institutions in Australia will not lend for such ventures or for new coal mining proposals. The commercial risk is deemed too high since energy from renewable sources is now generated and stored more cheaply than it can be from fossil fuels.

Subsidising the price at which future generation is sold could overcome this problem for proponents but it raises a moral – and political - question: Should Government use public money to subsidise increased emission of greenhouse gasses, particularly at a time when severity of weather events is increasing, making it an important issue for the electorate just prior to a General Election being held? The Coalition Government proposes doing so.

Demand

What then is the future for Australian coal? At best, bleak. As weather events increase in frequency, severity and destructiveness – and they will – calls for action to reverse this trend will increase in the form of pressure for governments of major coal burning countries to reduce the use of fossil fuels. If such action is not taken promptly, particularly by major coal producing and using countries, catastrophic weather events will become annual events, likely to force mass movement of people searching for the essentials of life.

This will place increasing pressure on major coal-using countries to speed-up their transition, away from coal use to cheaper forms of energy generation which do not emit greenhouse gasses. It will also place pressure on governments of major exporting countries as well as mine owners and operators to plan for retraining of displaced workers and find alternate sources of public revenue.

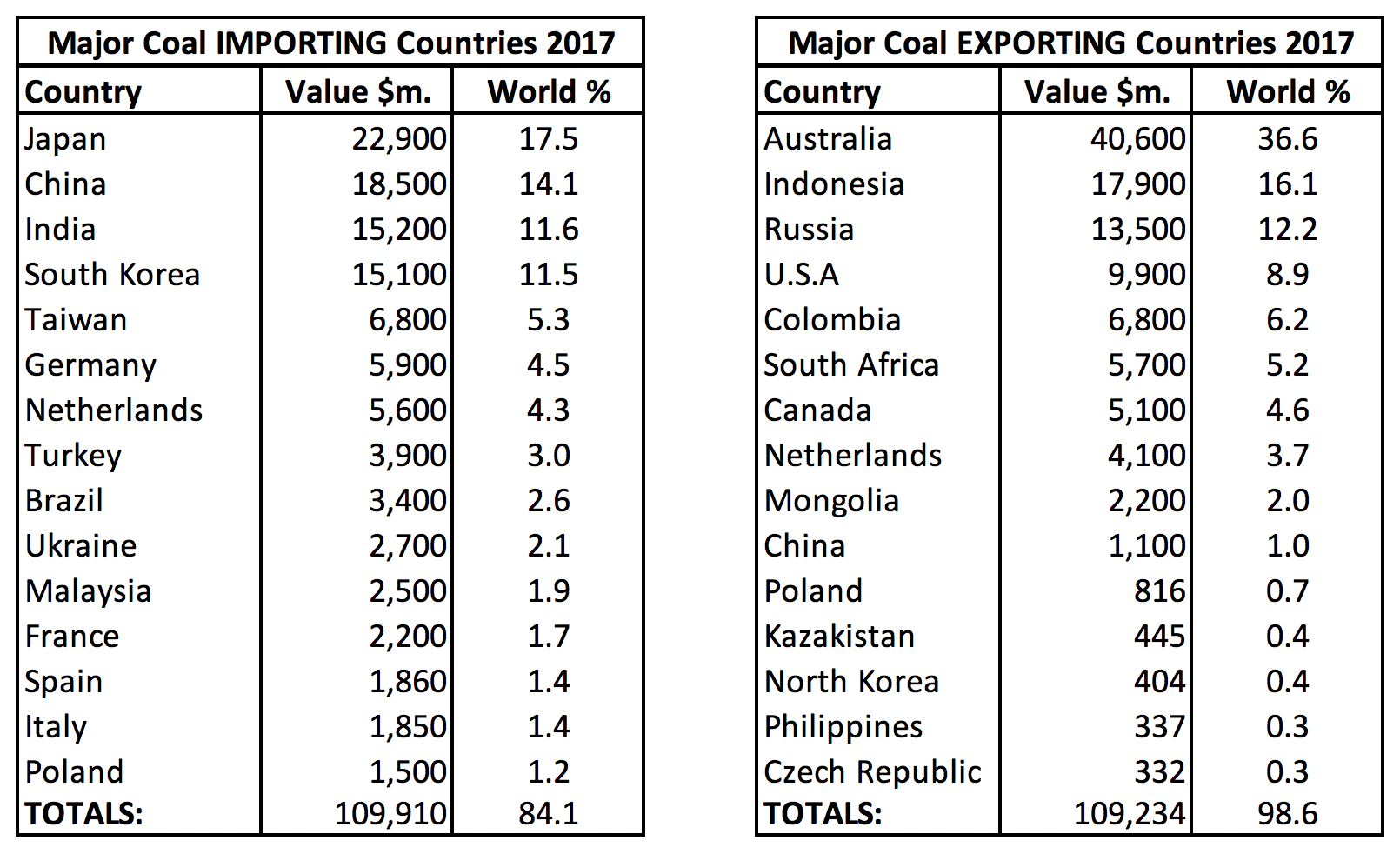

Fig 4. Tables listing the 15 leading countries importing and exporting coal in 2017. Note that some countries (eg. Netherlands) export much of their coal imports. Values in US$. Source for Import data. Source for Export data.

As shown above, the top 15 coal importers account for 84% of global coal imports while the top 15 exporters account for 98.6% of all such trade. It is the exporters who will be the hardest hit by any contraction in demand for coal – and Australia is at the top of that list.

Governments are faced with the task of preparing coal mining communities for contraction of coal mining in Australia with the least cost-efficient mines likely to be the first to close in the 2020's. The task of New South Wales and Queensland Governments, is to ascertain from mine operators the likely operating life of their assets and to approve their plans for environmental rehabilitation. Based on this knowledge, plans to sustain mining communities with other forms of development can be prioritised and developed.

Some politicians, particularly from the National Party, would have us believe that growth of coal use in Australia and overseas is a pressing necessity in order to protect mining communities from sudden mass unemployment, ensure continuity of electricity 24/7 and avoid closure of major industries in central Queensland. This as a ploy to differentiate the National Party from its coalition partner, the Liberal Party as a General Election date gets closer.

The rate at which Australian coal sales diminish will depend on the rate at which the largest importers are able to transition from using fossil-fuels to generate energy to cheaper renewable sources. It is very much in interest of major coal importing countries that they make this transition as rapidly as possible if the goods they produce are to remain competitive with goods made in countries which are moving rapidly towards using the cheapest electricity, that generated by solar, wind, hydro and other renewable sources. This move also conserves foreign exchange reserves now used to pay for coal imports, enabling their use for other purposes.

Major coal importers of Australian coal are moving away from fossil fuels to generate electricity. China and India, two of the larger importers, have indicated their intention of reducing seaborne coal imports over the next decade, while The Netherlands and Germany are likely to phase out use of imported coal by 2030.

On the other hand, ambivalent policy and lack of clear data trends from Japan and South Korea suggest continued imports at around present levels. Between them, they purchase 50% of Australian coal exports. However, pressure from the international community and the need to reduce the cost of electricity in order to remain competitive, could result in them shifting from coal to cleaner, cheaper electricity generation.

Australia is among a growing number of countries moving away from coal to cheaper renewable electricity. As shown by Fig 3, it expects to increase renewable generating capacity by at least 20 Gigawatts (GW) by 2022 and, at the same time, build energy storage sufficient to ensure continuity of electricity supply 24/7. It is likely that a further 20 GW of new capacity will be commissioned by 2026 to cope with economic growth and uptake of electric vehicles.

This could result in closure of all but 5 of the countries remaining 21 coal fired power stations, possibly by 2030, certainly before 2040 with loss of 70% of the domestic market and around $3 billion to Australian coal producers. By 2050, probably sooner, the domestic market for coal will cease to exist.

Conclusion

Claims by right-wing members of the Coalition Government that Australia is faced with an immediate threat to its coal industry are an exaggeration but there is no doubt that over the next decade, mine closures will occur as a result of declining demand for coal. This could result in the decline of coal mining communities over the next 30 years.

This is likely to be compensated for by creation of new industries such as mining of minerals demanded for storage and transmission of electricity, on shore processing of primary products rather than raw exports and innovations in production, storage, processing and transport of food and other goods.

Without such measures, the Australian economy could be severely damaged, not by on-going contraction and eventual loss of the coal industry but because of an increase in the severity and incidence of extreme weather events brought about by on-going global warming. The latter will affect all countries and cause greater economic losses which will eventually prove enduring because they are too costly to recover from.

Australia alone can not avert global outcomes – only effective action by all countries can achieve that – but the country should put itself in a position where it can join low-emitting countries in calling for and enforcing action on major emitters (see Imports Table/Fig. 4) to rapidly curb their emissions. If this is not achieved, we will all lose – permanently.

Arguments

Arguments

This is a clear, well composed, and well ordered article full of detail. Almost a textbook example.

On the contary to the first comment I think this is a very unclear article. After mentioning the difference between coking/metallurgical coal and thermal coal early in the article all mention of coking coal and its role in exports is dropped. Australia exports are a majority of coking coal (more than 60% of value I think) used to make steel and other metals. While using this coal adds to considerable greenhouse gas emissions, at the moment there is no other economically way to make steel (excluding recycling). So unless we are prepared to give up or severely reduce our use of steel we will need to mine and use large amounts of coking coal. On the other hand thermal coal is completely replaceable in the generation of electricity by gas, nuclear, solar, wind, tidal, wave etc. The article needs to explain this difference and hence the quite different future for Australian exports of coking coal (probably good) versus thermal coal (not so good as described). Of course Adani (and all the other proposed Galilee Basin mines) is a proposed thermal coal mine and that is why it is quite unlikely to ever go ahead.

jonb – thank you for your comment.

In 2018/19 the expected value of coking coal exports is a reported estimate of ~$38 billion and for thermal coal ~$28 billion, though both are predicted to decline in value in 2019/20. A downward trend in the value of Australian coal exports, seems likely to continue thereafter as coking coal is replaced by gas/electricity and thermal coal is replaced by solar/wind generators.

Thanks for the clarification. I'll just add that the replacement of coking coal to make steel and other metals with the use of direct electrical smelting or the use of gas will be a quite slow process due to economics - hence Australian coking coal exports will be fine for at least the next decade or so. On the other hand the replacement of thermal coal for electricity generation, both in Australia and around the world, will be and is a quick process by replacement by renewables (and gas) and is already happening quickly as the article mentioned.

Whether new coking coal mines are needed in Australia is difficult to say. This was brought up in the Rocky Hill court case in NSW and the judge decided (on what basis was not really shown) that no more coking coal mines were needed to meet Australian export needs. This case may be appealed - we'll see.

I am a little intrigued by the comment: "coking coal is replaced by gas/electricity".

My understanding is that making steel needs CO to reduction of Fe oxides, some carbon for the Fe-C alloy that is steel, and importantly, the porosity to allow the CO circulate within the furnace. I can see gas can provide CO, but the porosity? I know of bio-coke trials (happening here), but is there a commercial process for steel from iron ore without coke yet?

Here’s one possible technology being looked at

https://cleantechnica.com/2018/05/14/hydrogen-from-renewables-could-make-emissions-free-steel-possible/

[PS] Fixed link. Please learn how to do this yourself with the link tool in the comments editor.

This Scientific American article discusses using electricity directly to manufacture steel. It appears that it is possible to use electricity to manufacture steel directly. One issue is the cost of rebuilding current factories. If CO2 cost was high it would be more economic. How much do people want to reduce CO2?

Just curious. Is it possible to use the reducing power of hydrogen to make steel instead of coke.

Here is a reference

https://cleantechnica.com/2018/05/14/hydrogen-from-renewables-could-make-emissions-free-steel-possible/

Those references seem quite a long way from a commercially viable process for steel-making with coke. Or perhaps a better question would be what is the amount of a carbon tax that would make that commercially viable? My gut feeling is that even when you have a cost-competitive for making steel without coke, it would 30 years to wind down coke thanks to sunk costs in plant. "Green coke" might be a better migration path.

If steel and cement were the only source of fossil carbon emissions, would we still have a climate problem? The much more easily substitutable thermal coal would be first priority in my opinion.

Scaddenp

Sanjeev Gupta owner of the Whyalla Steel Mill in South Australia has announced investment to build renewable energy/storage projects with capacity of 1 GW dispatchable, part used by the Mill, part sold to the Grid. It is not clear that the Mill would use this energy source directly in the steel production process – I had assumed it would.

This now seems unlikely since Gupta has subsequently purchased a leading coking coal mine – billionaires can do that sort of thing. So your point is well made, though gas and electricity may be able to reduce reliance on coking coal for steel production in the future?

I was trying the link to the estimated 18 Billion Dollars 2018 worth of damage, and the 40 billion Dollars that coal brings to Australia, but they both are subscriber only articles in the Australian. Since I have no intention of giving any of my hard earned Dollars to the already obscenely rich, climate denier Murdoch, I was wondering if there are alternative sources for these figures. If they are correct, it suggests that already, nearly 50 percent of our earnings from Coal are need to clean up climate disasters. Why is this not being pushed more publicly? It is only going to get worse..

Australia has great potential for hydrogen production through electrolysis of water using electricity generated from renewable energy. In fact hydrogen produced in this way has already been exported to Japan and indicates growth of a whole new export industry.

Apart from use in fuel cells to drive emissions free electric cars, hydrogen can be used to replace coking coal in the production of emissions-free steel. This has already been trailed in Sweden and although the steel produced is presently more expensive than steel produced by coking coal the difference in price will reduce as the price of carbon rises.

Apparently hydrogen is used as a reduction agent in steel production, so provided the hydrogen is sourced from electrolysis of water using renewable energy, it could offer an alternative to present dependence on coking coal as a reduction agent.