What is the net feedback from clouds?

What the science says...

| Select a level... |

Basic

Basic

|

Intermediate

Intermediate

| |||

|

Evidence is building that net cloud feedback is likely positive and unlikely to be strongly negative. |

|||||

Climate Myth...

Clouds provide negative feedback

"Climate models used by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assume that clouds provide a large positive feedback, greatly amplifying the small warming effect of increasing CO2 content in air. Clouds have made fools of climate modelers. A detailed analysis of cloud behavior from satellite data by Dr. Roy Spencer of the University of Alabama in Huntsville shows that clouds actually provide a strong negative feedback, the opposite of that assumed by the climate modelers. The modelers confused cause and effect, thereby getting the feedback in the wrong direction." (Ken Gregory)

At a glance

What part do clouds play in your life? You might not think about that consciously, but without clouds, Earth's land masses would all be lifeless deserts. Fortunately, the laws of physics prevent such things from being the case. Clouds play that vital role of transporting water from the oceans to land. And there's plenty of them: NASA estimates that around two-thirds of the planet has cloud cover.

Clouds form when water vapour condenses and coalesces around tiny particles called aerosols. Aerosols come in many forms: common examples include dust, smoke and sulphuric acid. At low altitudes, clouds consist of minute water droplets, but high clouds form from ice crystals. Low and high clouds have different roles in regulating Earth's climate. How?

If you've ever been in the position to look down upon low cloud-tops, perhaps from a plane or a mountain-top, you'll have noticed they are a brilliant white. That whiteness is sunlight being reflected off them. In being reflected, that sunlight cannot reach Earth's surface - which is why the temperature falls when clouds roll in to replace blue skies. Under a continuous low cloud-deck, only around 30-60% of the sunlight is getting through. Low clouds literally provide a sunshade.

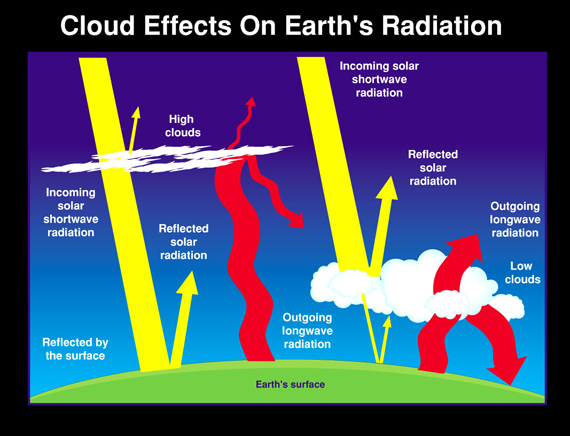

Not all clouds are such good sunshades. Wispy high clouds are poor reflectors of sunlight but they are very effective traps for heat coming up from below, so their net effect is to aid and abet global warming.

Cloud formation processes often take place on a localised scale. That means their detailed study involves much higher-resolution modelling than the larger-scale global climate models. Fourteen years on, since Ken Gregory of the dubiously-named Big Oil part-funded Canadian group, 'Friends of Science', opined on the matter (see myth box), big advances have been made in such modelling. Today, we far better understand the net effects of clouds in Earth's changing climate system. Confidence is now growing that changes to clouds are likely to amplify, rather than offset, human-caused global warming in the future.

Two important processes have been detected through observation and simulation of cloud behaviour in a warming world. Firstly, just like wildlife, low clouds are migrating polewards as the planet heats up. Why is that bad news? Because the subtropical and tropical regions receive the lion's share of sunshine on Earth. So less cloud in these areas means a lot more energy getting through to the surface. Secondly, we are detecting an increase in the height of the highest cloud-tops at all latitudes. That maintains their efficiency at trapping the heat coming up from below.

There's another effect we need to consider too. Our aerosol emissions have gone up massively since pre-Industrial times. This has caused cloud droplets to become both smaller and more numerous, making them even better reflectors of sunlight. Aerosols released by human activities have therefore had a cooling effect, acting as a counter-balance to a significant portion of the warming caused by greenhouse gas emissions.

But industrial aerosols are also pollutants that adversely affect human health. Having realised this, we are reducing such emissions. That in turn is lowering the reflectivity of low cloud-tops, reducing their cooling effect and therefore amplifying global warming due to rising levels of greenhouse gases.

It sometimes feels as if we are between a rock and a hard place. We'd have been better off not treating our atmosphere as a dustbin to begin with. But there's still a way to fix this and that is by reducing all emissions.

Please use this form to provide feedback about this new "At a glance" section. Read a more technical version below or dig deeper via the tabs above!

Further details

The IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report eloquently sums up where we are in our understanding of how clouds will affect us in a changing climate:

"One of the biggest challenges in climate science has been to predict how clouds will change in a warming world and whether those changes will amplify or partially offset the warming caused by increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases and other human activities. Scientists have made significant progress over the past decade and are now more confident that changes in clouds will amplify, rather than offset, global warming in the future."

The mistake made by our myth-provider, writing in 2009, was to leap to a conclusion without the information needed in order to do so. He is suggesting that clouds are inadequately represented in climate models, so they must have a negative effect on temperatures. Instead of making such leaps of faith, however, the specialists in cloud behaviour have recognised the challenges and met them square-on. We now know a lot more about clouds as a result.

In the at-a-glance section, we explain the important difference between high clouds and low clouds, agents of warming and cooling respectively. Careful examination of older satellite records has detected large-scale patterns of cloud change between the 1980s and 2000s (Norris et al. 2016). Observed and simulated cloud change patterns are consistent with the poleward retreat of midlatitude storm tracks, the expansion of subtropical dry zones and increasing height of the highest cloud tops at all latitudes. The main drivers of these cloud changes appear to be twofold: increasing greenhouse gas concentrations and recovery from volcanic radiative cooling. As a result, the cloud changes most consistently predicted by global climate models have indeed been occurring in nature.

With respect to the cooling low clouds, one particularly important area of study has involved marine stratocumulus cloud-decks. These are extensive, low-lying clouds with tops mostly below 2 km (7,000 ft) altitude and they are the most common cloud type on Earth. Over the oceans, stratocumulus often forms nearly unbroken decks, extending over thousands of square kilometres. Such clouds cover about 20% of the tropical oceans between 30°S and 30°N and they are especially common off the western coasts of North and South America and Africa (fig.1). That's because the surface waters of the oceans are pushed away from the western margins of continents due to the eastwards direction of Earth's spin on its axis. Taking the place of these displaced surface waters are upwelling, relatively cool waters from the ocean depths. The cool waters serve to chill the moist air above, making its water vapour content condense out into cloud-forming droplets.

Fig. 1: visible satellite image of part of an extensive marine stratocumulus deck off the western seaboard of North America, with Baja California easily recognisable on the right. Image: NASA.

With their highly reflective tops that block a lot of the incoming sunlight, the marine stratocumulus clouds have a very important role as climate regulators. It has long been known that increasing the area of the oceans covered by such clouds, even by just a few percent, can lead to substantial global cooling. Conversely, decreasing the area they cover can lead to substantial global warming.

Although many cloud-types are produced by convection, driven by the heated land or ocean surface, marine stratocumulus clouds are different. They are formed and maintained by turbulent overturning circulations, driven by radiative cooling at the cloud tops. It works as follows: cold air sinks, so that radiatively-cooled air makes its way down to the sea surface, picks up moisture and then brings that moisture back up, nourishing and sustaining the clouds.

Stratocumulus decks can and do break up, though. This happens when that radiative cooling at the cloud tops becomes too weak to send colder air sinking down to the surface. It can also occur when the turbulence that can entrain dry and warm air, from above the clouds into the cloud layer, becomes too strong.

The importance of such processes has been further investigated recently, using an ultra-high resolution model with a 50-metre grid size. (Schneider et al. 2019). Global climate models typically have grid sizes of tens of kilometres. At that resolution, they cannot detail such fine-scale processes. This model, by contrast, is able to resolve the individual stratocumulus updraughts and downdraughts.

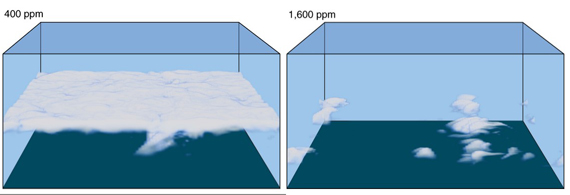

Fig. 2: results of modelling of marine stratocumulus behaviour in a high-CO2 world. This one compares conditions at 400 ppm (present) and 1600 ppm (hopefully never, but relevant to the Palaeocene and Eocene when a super-Hothouse climate prevailed). Redrawn from Schneider et al. 2019.

The modelling shows how oceanic stratocumulus decks become unstable and break up into scattered cumulus clouds. That occurs at greenhouse gas levels of around 1,200 ppm (fig. 2). When that happens, the ocean surface below the clouds warms abruptly because the cloud shading is so diminished. In the model, the extra solar energy absorbed as stratocumulus decks break up, over an area estimated to cover about 6.5% of the globe, is enough to cause a further ~8oC of global warming. After the stratocumulus decks have broken up, they only re-form once CO2 levels have dropped substantially below the level at which the instability first occurred.

These results point to the possibility that there is a previously undiscovered, potentially strong and nonlinear feedback, lurking within the climate system. These findings may well help to solve certain palaeoclimatic problems, such as the super-Hothouse climate of the Palaeocene-Eocene, some 50 million years ago. It's been hard to fully explain that event, given that estimates of CO2 levels at the time do not exceed 2,000 ppm. Present climate models do not reach that level of warmth with that amount of CO2. But the fossil record presents hard evidence for near-tropical conditions in which crocodilians thrived - in the Arctic. Something brought about that climate shift!

The quantitative aspects of stratocumulus cloud-deck instability remain under investigation. However the phenomenon appears to be robust for the physical reasons described by Schneider and co-authors. Closer to the present, the recent acceleration of global warming may be partly due to a decrease in aerosols. Aerosols produce smaller and more numerous cloud droplets. These have the effect of increasing the reflectivity and hence albedo of low cloud-tops (fig. 3). It follows that if aerosol levels decrease, the reverse will be the case. Of considerable relevance here are the limits on the sulphur content of ship fuels, imposed by the International Maritime Organization in early 2015. These regulations were further tightened in 2020. An ongoing fall in aerosol pollution, right under the marine stratocumulus decks, would be expected to occur. As a consequence, the size and amount of cloud droplets would change, cloud top albedo would decrease and there would be increased absorption of solar energy by Earth. That would be on top of the existing greenhouse gas-caused global warming. James Hansen discussed this in a recent communication (PDF) here.

Fig. 3: NASA graphic depicting the relationship between clouds, incoming Solar radiation and long-wave Infrared (IR) radiation. High clouds composed of ice crystals reflect little sunlight but absorb and emit a significant amount of IR. Conversely low clouds, composed of water droplets, reflect a great deal of sunlight and also absorb and emit IR. Any mechanism that reduces low cloud-top albedo will therefore increase the sunlight reaching the surface, causing additional warming.

In their Sixth Assessment Report, the IPCC also points out that the concentration of aerosols in the atmosphere has markedly increased since the pre-industrial era. As a consequence, clouds now reflect more incoming Solar energy than before industrial times. In other words, aerosols released by human activities have had a cooling effect. That cooling effect has countered a lot of the warming caused by increases in greenhouse gas emissions over the last century. Nevertheless, they also state that this counter-effect is expected to diminish in the future. As air pollution controls are adopted worldwide, there will be a reduction in the amount of aerosols released into the atmosphere. Therefore, cloud-top albedo is expected to diminish. Hansen merely suggests this albedo-reduction may already be underway.

Last updated on 15 October 2023 by John Mason. View Archives

Arguments

Arguments

Licorj - I would suggest following the links in the opening post; there is considerable evidence for a small positive cloud feedback based on observations, on constraints from other forcings and feedbacks, from paleo evidence, etc.

Not a "game", not a guess - a small positive feedback comes from the best estimates of the various evidence available.

Licorj @250, by "estimate", it is meant estimate based on empirical observations and predictions from models. Both, separately, suggest that a small positive cloud feedback is more likely than not. The uncertainty is large so that negative feedbacks are not excluded, but neither are large positive feedbacks excluded.

You say that to get the true cloud feedback, we need lots of measurements around the world. Those measurements have been done. Three examples of such measurements are linked to in the OP. Unfortunately the measurements do not tightly constrain the result because the feedback is complicated and the observational data is noisy.

Of course, it is always possible to avoid the whole issue by looking at empirical estimates of the net feedback from historical and paleo data. These overwhelmingly suggest a large net positive feedback. As these are estimates based on what has actually occured on the Earth, they of necessity include all feedbacks. Therefore, if the cloud feedback does in fact turn out to be negative, that merely means that some other combination of feedbacks is more strongly positive than currenly estimated.

On Safari, the final link to the Steven Sherwood video is broken. There appears to be a leading '/' that shouldn't be there.

Speaking of clouds and manmade climate change, here’s a handy reference document recently published by the WMO…

Humanity has a primordial fascination with clouds. The meteorological and hydrological communities have come to understand through decades of observation and research that cloud processes – from the microphysics of initial nucleation to superstorms viewed from satellites – provide vital information for weather prediction, and for precipitation in particular. Looking at clouds from a climate perspective introduces new and difficult questions that challenge our overall assumptions about how our moist, cloudy atmosphere actually works.

Clouds are one of the main modulators of heating in the atmosphere, controlling many other aspects of the climate system. Thus, “Clouds, Circulation and Climate Sensitivity” is one of the World Climate Research Programmes (WCRP) seven Grand Challenges. These Grand Challenges represent areas of emphasis in scientific research, modelling, analysis and observations for WCRP and its affiliate projects in the coming decade.

Understanding Clouds to Anticipate Future Climate by Sandrine Bony, Bjorn Stevens & David Carlson, Bulletin nº Vol 66 (1) – 2017

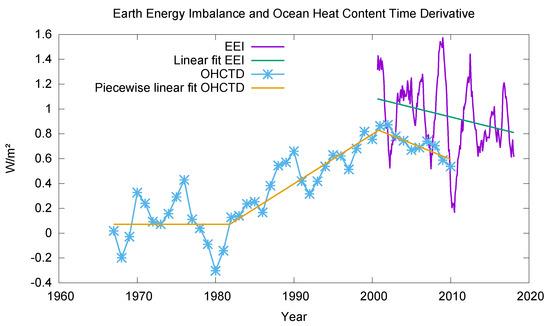

Interesting paper finds "surprising" results from CERES with a negative trend of Earth Energy Imbalance as well as a negative trend of Ocean Heat Content Time Derivative :

"Decadal Changes of the Reflected Solar Radiation and the Earth Energy Imbalance" by Dewitte , Clerbaux and Cornelis.

Abstract: Decadal changes of the Reflected Solar Radiation (RSR) as measured by CERES from 2000 to 2018 are analysed. For both polar regions, changes of the clear-sky RSR correlate well with changes of the Sea Ice Extent. In the Arctic, sea ice is clearly melting, and as a result the earth is becoming darker under clear-sky conditions. However, the correlation between the global all-sky RSR and the polar clear-sky RSR changes is low. Moreover, the RSR and the Outgoing Longwave Radiation (OLR) changes are negatively correlated, so they partly cancel each other. The increase of the OLR is higher then the decrease of the RSR. Also the incoming solar radiation is decreasing. As a result, over the 2000–2018 period the Earth Energy Imbalance (EEI) appears to have a downward trend of −0.16 ± 0.11 W/m2dec. The EEI trend agrees with a trend of the Ocean Heat Content Time Derivative of −0.26 ± 0.06 (1 σ) W/m2dec.

...

"The Earth Energy Imbalance (EEI) shows a trend of −0.16 ± 0.11 W/m2dec. The decreasing trend in EEI is in agreement with a decreasing trend of −0.26 ± 0.06 W/m2dec in the Ocean Heat Content Time Derivative (OHCTD) after 2000.

The OHCTD over the period 1960–2015 shows three different regimes, with low OHCTD prior to 1982, rising OHCTD from 1982 to 2000, and decreasing OHCTD since 2000. These OHCTD periods correspond to periods of slow/rapid/slow surface temperature rise [16,17], to periods of strong La Ninas/El Ninos/La Ninas [14,18], and to periods of increasing/decreasing/increasing aerosol loading [19,20]. "

https://www.mdpi.com/2072-4292/11/6/663/htm#

Hefaistos @255 ,

please comment on the Dewitte et al., 2019 paper you cite.

My first impression of the EEI graph is (ignoring error bars) that it's very noisy.

To this layman, a new report (Saint‐Lu et al 2020) seems to support Lindzen's "Iris effect" (that high cloud cover in the tropics diminish with increased temperature), but at the same time finds that high clouds have a neutral effect on global warming:

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2020GL089059

Quick question on cloud feedbacks in particular and other feedbacks in particular. If every feedback we have is positive, and we know that way back in time CO2 was 30* current levels, wouldn't the earth have had runaway warming? Doesn't the fact that it didn't mean that some of the feedbacks must be negative, and indeed dominate in higher temperature regimes? What are the explanations for why 600-400 mya, there wasn't runaway warming? Was it the tilt of the earth, the sun, or some other astronomical feature that was very different, or was it a not yet understood feedback? Thanks

Some feedbacks are negative, some are positive. So long as the total sum of all feedbacks is less than 1 in either direction, there can be no runaway warming or freezing. There is plenty of info on that from a variety of sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Climate_change_feedback

sunnyx @258,

The level of CO2 in the atmosphere during the early Earth is usually assumed to be very high because the sun was a lot weaker (it has been brightening by something like 5% every billion years) and we know from rocks that there was liquid water so the Earth could not have been very cold. For the period back to 500My the CO2 level can be assessed from proxy data and also modelled. This shows CO2 was a lot higher than today for most of the last 500My. The impact on the climate is a matter of how many doublings of CO2. So three or four doublings would suggest a climate something like 10ºC-13ºC warmer. But the loss of 2½% of solar heating with the weaker sun back 500My would equal perhaps two of those CO2 doublings. So much of the climate forcing of the additional CO2 was negated by there being a cooler sun.

Changes in climate result from the feedbacks as well as the CO2/solar forcing and will not have chaned greatly. But the net feedback would have to be large to have caused a runaway warming. Imagine ECS=3ºC. That is the net feedback (the sum of positive and negative) result in trebling the temperature increase initially caused by the CO2. But that is all you get - a trebling. It would take a stonger net feedback to become runaway (actually 50% stronger).

(The ECS=3ºC is a compound result in that the warming of the feedback itself induces feedbacks. The trebling of ECS=3ºC is equivalent to a simple feedback of 0.67. As Philippe Chantreau @259 says, the magic number to achieve runaway is 1.0, an increase on 0.67 of 50%.)

I hope that makes sense for you.

CRE / cloud radiative effect (-19Wm-2)

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00382-018-4413-y

...please do not confuse with

CRF / cloud radiative feedback (+0,42Wm-2 °C-1)

https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Chapter_07.pdf page 74

[BL] Links activated.

The web software here does not automatically create links. You can do this when posting a comment by selecting the "insert" tab, selecting the text you want to use for the link, and clicking on the icon that looks like a chain link. Add the URL in the dialog box.

Pleas also note that the Comments Policy here discourages pasting just links or images:

If you have a point to make, please state it, and make sure that it is on topic for the discussion.

Being a layman, it seems to me that the normal water cycle cools the surface through conduction and evaporation. That energy is eventually released to the upper atmosphere through convection and condensation of cloud formation. Low warm clouds in turn will block more radiation from the sun keeping the ground cooler, negative feedback: Johannes Mulmenstadt et al 6/3/2021 paper.

"As the atmosphere warms, part of the cloud population shifts from ice and mixed-phase (‘cold’) to liquid (‘warm’) clouds. Because warm clouds are more reflective and longer-lived, this phase change reduces the solar flux absorbed by the Earth and constitutes a negative radiative feedback."

See an article about this paper "Cooling effect of clouds ‘underestimated’ by climate models, says new study"

This process seems that it would cause self regulation of the temperature of the atmosphere preventing the possibility of the atmosphere from ever overheating and becoming uninhabitable, i.e. runaway warming. Maybe in a repeating cycle such as more co2=>more warming=>More h2o=>more warm cloud cover=>more cooling=>less co2=>less heating=>less h2o=>less warm cloud cover=>more heating=>more co2 and so on. This seems that it could cause long periods of heating and cooling, maybe decades. Let me know where I'm wrong.

I always thought it was cooler on cloudy days than sunny days.

Likeitwarm @26 :

Yes, it seems cooler on cloudy days than sunny days ~ during daytime.

But warmer nights, when it is cloudy.

Overall effect, rather close to neutral.

The paleo evidence shows no "runaway" , but it does show that the global climate can become very hot indeed.

Likeitwarm:

The paper by Mulmenstadt et al that you mention was covered in this blog post at Skeptical Science, around the time it first appeared. (SkS reposted the Carbon Brief article.)

In that post, a key summary is:

However, the lead author of the study tells Carbon Brief that fixing the “problem” in rainfall simulations “reduces the amount of warming predicted by the model, by about the same amount as the warming increase between CMIP5 and CMIP6”.

So, the results are not as earth-shattering as you seem to want to imply. Uncertainties in cloud feedback are a well-known part of climate modelling and understanding, and this paper represents one more small step in helping understand the consequences.

As for your description of the water cycle:

As for your discussion of "runaway warming" - nobody is predicting such a result due to CO2, so you are arguing a strawman.

And as to "self regulation of the temperature of the atmosphere" - the simple fact that climate has changed in many ways, for many reasons, over centuries and millenia is strong evidence that this is not true. Perhaps try reading the "Climate's changed before" post that reponds to our number 1 myth listed in our "Most Used Climate Myths" in the top left sidebar of all our pages.

I have worked through some darn cold sunny days in winter - much colder than overcast days in summer - to illustrate how incomplete your cloudy/sunny day closing statement is.

Bob Loblaw:

Thanks for taking the time to point out my mis-understandings.

I didn't realize the article had been posted to SkS. It was news to me. I should have figured climate hawks like yourself would have read it. My mistake.

I will keep reading and post any questions I might have.

Best to you.

Bob Loblaw:

If there is no prediction of runaway heating, what is all the hub-bub about CO2?

Likeitwarm: what exactly do you mean by "runaway heating"? Unless you are willing to define your term, you are playing word games.

If CO2 content stabilizes at any point (450, 500, 600ppm, take your pick) then temperature will stablize at some new value (2, 3, 4 or more degrees warmer than it was at 300ppm CO2), and it will not continue to increase indefinitely. It will not "run away". But that new, stable temperature will have plenty of bad consequences.

Even if we were to manage to burn every gram of fossil fuel we can find, and raise CO2 to 1200ppm or more, we still won't see a perpetually-increasing temperature. No "runaway". A new equilibrium will be found. There is no reason to expect anything like Venus.

After all, body temperature is only 37C (98.6F), and if you get a fever and your temperature goes up to 41C and stabilizes at that point, you still run a pretty large risk of death. Your body temperature does not need to keep rising more ("runaway") to be a serious problem.

Unless you have some other (odd) definition of "runaway".

Should you wish to discuss "runaway greenhouse effect" myths, there are two possible threads here:

https://skepticalscience.com/Venus-runaway-greenhouse-effect.htm

https://skepticalscience.com/positive-feedback-runaway-warming.htm

It would be worth your time to read those posts (and possibly the comments) in full.

Likeitwarm,

The last time that CO2 was 400 ppm (It is currently 419 ppm) the sea level was over 23 meters higher than it is now. That amount of rise would flood most of the major cities worldwide and inundate a very large fraction of the best farmland in the world. I could go on with bad effects but those are enough to give any thinking person fits. I note that sea level rise accelerated rapidly the last ten years and is now over 10 mm per year. Pray that it goes back down.

Bob Loblaw:

I just meant warming to a point that causes unacceptable harm to human habitation. Maybe "runaway" is the wrong term. Maybe "harmfully warm" would be better.

I'm just posting what I think to see where I'm right or wrong. I appreciate your input. I'm going to withhold posting until I do more reading.

Likeitwarm:

"Runaway" is very definitely the wrong term for what you are asking.

You should start by reading the post that shows up as #3 on the list of Most Used Climate Myths (top left side bar of every screen here).

https://skepticalscience.com/global-warming-positives-negatives.htm

Maybe go down the list, where you will probably continue to find material for many of the questions you seem to want to ask.

Please note: the basic version of this rebuttal has been updated on October 15, 2023 and now includes an "at a glance“ section at the top. To learn more about these updates and how you can help with evaluating their effectiveness, please check out the accompanying blog post @ https://sks.to/at-a-glance