Nordhaus Sets the Record Straight - Climate Mitigation Saves Money

Posted on 2 March 2012 by dana1981

Yale's William Nordhaus is one of the foremost experts on climate economics. His research has frequently been misrepresented by climate "skeptics" to argue that CO2 limits will harm the economy. For example, Christopher Monckton cited a climate economics review by Richard Tol (which in turn heavily cited work by Nordhaus) in claiming:

"...the overwhelming majority of economic studies on the subject (which are summarized in my paper) find the cost of climate action greatly exceeds the cost of inaction..."

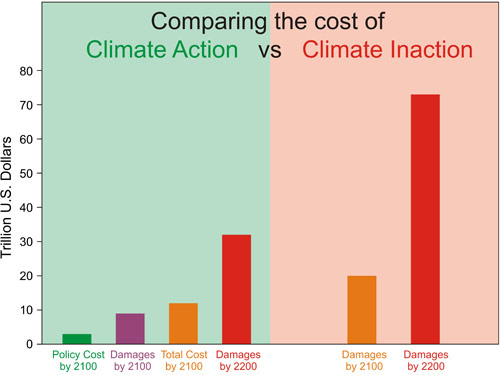

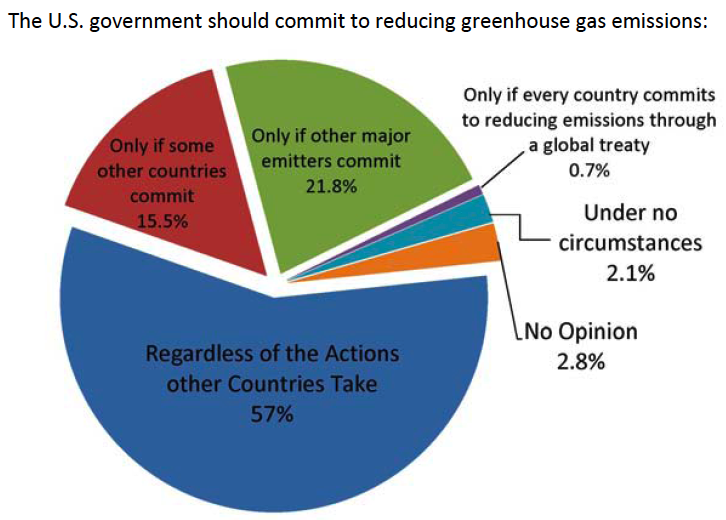

As we demonstrated in our response, Monckton completely misrepresented the work of Tol (and Nordhaus, by extension), and thus his claim is 100% wrong. The reality is that the overwhelming majority of economic studies on climate find the cost of climate inaction greatly exceeds the cost of action (Figure 1). That's why there is a consensus amongst economists with climate expertise that we should reduce greenhouse gas emissions (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Approximate costs of climate action (green) and inaction (red) in 2100 and 2200. Sources: German Institute for Economic Research and Watkiss et al. 2005

Figure 2: New York University survey results of economists with climate expertise when asked under what circumstances the USA should reduce its emissions

Similarly, a recent letter published by the Wall Street Journal, signed by 16 climate "skeptics" (few of which have any climate or economics expertise, and many of which have received fossil fuel funding) misrepresented Nordhaus' research as supporting climate inaction from an economic standpoint. When Nordhaus objected to this misrepresentation of his work, Patrick Michaels doubled-down on the misrepresentation, claiming Nordhaus didn't understand his own research.

However, as discussed by Alex C on Skeptical Science, the "skeptics" had indeed misrepresented Nordhaus' work. They focused on the cost-to-benefit ratio of various climate mitigation options, whereas it is the difference (benefit minus cost, as opposed to benefit divided by cost) which tells us how much money is saved, and thus is the most important factor in determining which option is most economically beneficial.

In a recent article, Nordhaus sought to set the record straight that the climate economics literature clearly indicates that CO2 limits will save money. Nordhaus confirmed that the SkS approach is the correct one:

"The authors cite the “benefit-to-cost ratio” to support their argument. Elementary cost-benefit and business economics teach that this is an incorrect criterion for selecting investments or policies. The appropriate criterion for decisions in this context is net benefits (that is, the difference between, and not the ratio of, benefits and costs).

This point can be seen in a simple example, which would apply in the case of investments to slow climate change. Suppose we were thinking about two policies. Policy A has a small investment in abatement of CO2 emissions. It costs relatively little (say $1 billion) but has substantial benefits (say $10 billion), for a net benefit of $9 billion. Now compare this with a very effective and larger investment, Policy B. This second investment costs more (say $10 billion) but has substantial benefits (say $50 billion), for a net benefit of $40 billion. B is preferable because it has higher net benefits ($40 billion for B as compared with $9 for A), but A has a higher benefit-cost ratio (a ratio of 10 for A as compared with 5 for B). This example shows why we should, in designing the most effective policies, look at benefits minus costs, not benefits divided by costs."

Nordhaus went on to further dispel the myth that CO2 limits will hurt the economy. In fact, the opposite is true:

"My research shows that there are indeed substantial net benefits from acting now rather than waiting fifty years. A look at Table 5-1 in my study A Question of Balance (2008) shows that the cost of waiting fifty years to begin reducing CO2 emissions is $2.3 trillion in 2005 prices. If we bring that number to today’s economy and prices, the loss from waiting is $4.1 trillion. Wars have been started over smaller sums.

My study is just one of many economic studies showing that economic efficiency would point to the need to reduce CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions right now, and not to wait for a half-century. Waiting is not only economically costly, but will also make the transition much more costly when it eventually takes place. Current economic studies also suggest that the most efficient policy is to raise the cost of CO2 emissions substantially, either through cap-and-trade or carbon taxes, to provide appropriate incentives for businesses and households to move to low-carbon activities."

[...]

"The claim that cap-and-trade legislation or carbon taxes would be ruinous or disastrous to our societies does not stand up to serious economic analysis. We need to approach the issues with a cool head and a warm heart. And with respect for sound logic and good science."

Despite the economic reality that CO2 limits will save money, the myth that they will harm the economy is a pervasive one. However, this myth is based on nothing more than a misunderstanding of climate science and economics, and misrepresentation of the climate science and economics body of research.

Note: this information has been incorporated into the rebuttal to the myth "CO2 limits will harm the economy"

Arguments

Arguments

0

0  0

0

Comments