Publishing a long overdue explainer about a scientific consensus

Posted on 30 November 2022 by BaerbelW

Recently, we happened upon a neat and detailed article, explaining what a scientific consensus is. This made us realize, that - even though we have a lot of material about the consensus - we were lacking an explainer about what a scientific consensus actually is. We have now remedied this and created a page with an explainer and an accompanying glossary entry which will point our readers towards that page with a small pop-up-box whenever they hover the cursor over the word “consensus” in an article or rebuttal on Skeptical Science. The full text is available below with the sections about the knowledge-based consensus based on the script of Peter Jacob's related lecture in week 1 of Denial101x.

Introduction

You’ll most likely have seen instances where the term “scientific consensus” has been misused or misunderstood. People for example often confuse it with appeals to popular opinion or think it is the result of discussions or determined by a vote or just finding a compromise. Because of this, opinion polls - even if predominated by unqualified individuals - are used to argue that no scientific consensus exists for a particular topic even if it clearly does.

It’s important to note that a scientific consensus is not proof for a scientific theory but that it’s the result of converging lines of evidence all pointing to the same conclusion. It is therefore not a part of the scientific method but is actually a consequence of it. When people argue against a scientific consensus, they are usually misunderstanding the term or are deliberately abusing the ambiguity of the term consensus. A scientific consensus is not infallible but nonetheless represents the best knowledge available on a given scientific topic at a given time. In addition, it provides the foundation for new knowledge by generating follow-up questions for scientists to explore.

A scientific consensus is not a show-of-hands as it looks like in the cartoon below at first sight! It's more like "Yes, because of the evidence we all agree that humans are causing climate change". The consensus is not evidence of global warming – it evolved over more than 100 years from the evidence.

Defining Scientific Consensus

A “consensus” in everyday usage typically refers to a popular opinion which doesn’t need to be based on actual knowledge or evidence. By contrast, a “scientific consensus” needs to be based on evidence and converging lines of existing evidence are a prerequisite, distinguishing a knowledge-based scientific consensus from a simple agreement. To quote John Reisman, “Science is not a democracy. It is a dictatorship. It is evidence that does the dictating.” Because of that, a few disagreeing contrarians on the fringe don’t really matter unless and until they can show evidence of comparable weight which explains the existing data and observations better. The weight of evidence is what matters.

You need to have a convergence of many independent lines of high quality evidence leading the vast majority of active - i.e. publishing - scientists in a given field to come to the same or complimentary conclusions before you can refer to a consensus in science. Given the combative nature of science, it’s highly unlikely, that any scientist sets out to become part of a consensus. However, many will discover that their research results led them to become one piece of the puzzle making up the overall consensus. Reaching a scientific consensus is not straightforward, will vary by field and might well resemble a “long, long winding road” with quite a few dead ends and detours thrown in along the way.

An absolute 100% unamity among scientists in a specific field is neither likely nor a prerequisite for a scientific consensus as long as there’s a consilience of evidence in support of a particular conclusion. Outlier viewpoints within the scientific community are therefore quite normal and there’s usually nothing nefarious going on.

Knowledge-based Consensus

The following image illustrates the defining criteria for a knowledge-based consensus. We’ll take a closer look at each of them in the sections below.

Consilience of Evidence

Consilience means having many lines of evidence that are independent from, but in agreement with one another, which all point to the same conclusion. A scientific consensus should therefore be based on varied lines of evidence which independently converge on the same conclusion or set of conclusions (Miller 2013). There’s no need for the scientists and their results to agree on every small detail and it’s okay for the data converging within a set of error bars. It is enough when all lines point to the same general conclusion. Ideally, contributions from different scientific areas provide pieces for a broader understanding or set of conclusions.

Taking the scientific consensus in climate science as an example, it’s apparent that evidence and knowledge comes from many different areas, like meteorology, geology, geophysics, geochemistry, atmospheric physics, atmospheric chemistry and planetary science to name just a few obvious ones. Different specialities are involved, leading scientists to study different aspects of the issue but still arriving at results consistent with the conclusion that the recent warming trend has been largely due to human activities (Oreskes 2004, Doran & Zimmerman 2009, Cook et al. 2016).

Piecing together a puzzle

Imagine a friend who is cleaning out his old games and gives you a large bunch of puzzle pieces. He was cleaning in a hurry, and just threw pieces in an old shoebox. You don’t know what the puzzle will look like, or even if the pieces are really all from the same puzzle. Maybe the pieces all look like they’re showing something similar, but don’t actually fit together. Or maybe the puzzle pieces sort of fit together, but look like they would have to come from very different pictures. When pieces of the puzzle fit together and show a picture that makes sense, you can be confident that you’re on the right track.

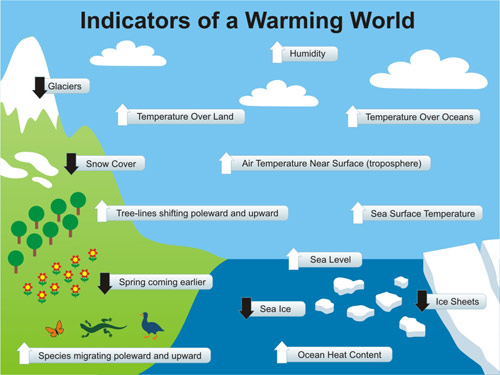

Science depends on evidence coming together and telling the same story. When we look at the average temperature of the earth, we can see a bunch of different lines of evidence pointing to the same conclusion. Thermometers on the ground, on ships in the ocean, and on balloons in the air all show an increase in temperature. Glaciers around the world are melting. Sea level is rising. Moisture in the air is increasing. All of these things tell us the world is getting hotter. The puzzle pieces fit together and the picture is clear.

Social Calibration

Evidence is a big part of what makes science successful. And that means we have to make sure we’re all using the same standards of evidence and speaking the same language, figuratively at least. We call this Social Calibration. It may sound obvious, but people need to be in agreement about the concepts they’re discussing before they can come to a meaningful conclusion.

There is a commitment among experts to employ the same high standards of evidence for which there are good justifications (Miller 2013). Carefully collected and reproducible evidence is key in science but it has to be interpreted by scientists. The Social Calibration criterion has to do with what the scientific community as a whole accepts as evidence, how they decide what is relevant and significant, and how individual scientists persuade their peers that they are correct.

To be able to address the question of whether the planet is warming, you have to agree on some basic concepts. It might sound silly, but there are climate contrarians who deny that there even is such a thing as a global temperature. But of course we can take temperature measurements from across the planet to get an average global temperature.

People need to agree on what counts as a valid way of answering a question as well. Someone might feel that the answer was revealed to him in a dream. Someone else might claim to have found an answer in an ancient prophecy. But when dealing with scientific questions, it’s important that we’re relying on the rigorous standards of scientific inquiry. For more about how science works, check out this article by Melanie Trecek-King.

Social Diversity

But Consilience of Evidence and Social Calibration might still not be enough. To be really confident that consensus is correct, it also helps to see agreement coming from many different groups from many different backgrounds. In other words, we also want to see Social Diversity. This criterion ensures that a scientific consensus is not a product of group think, politics, financial incentives, ideological motives, or shared cultural values.

To understand why, it helps to look at cases in which a lack of Social Diversity can lead to the wrong conclusions.

One is plain old bad luck. It is always possible to reach a conclusion of “yes” when the correct answer is “no” or vice versa. It could be a statistical fluke. Or contaminated materials. Or even something dependant on the location of the group performing the experiment. Having many different groups from many different backgrounds can do a lot to rule out such problems.

Another way in which a lack of diversity can lead to agreement that turns out to be wrong is groupthink. There is a tendency for groups of small numbers or highly similar groups to attempt to minimize disagreement and promote conformity. A desire for harmony within the group can cause people to ignore reservations they may have, and reach agreement for the sake of agreeing, rather than weighing the evidence. A large, diverse group will have less of an inclination towards groupthink, as differences among the group exist from the outset.

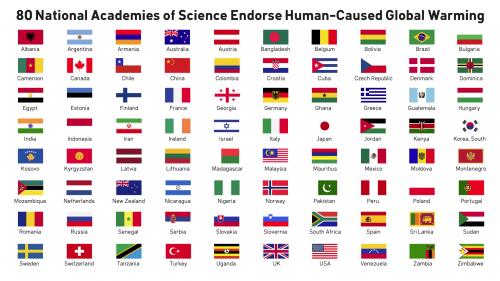

Cultural bias is another way in which a lack of diversity can lead to incorrect conclusions. Scientists are products of their cultures, and different cultures have different preferences for how the world should be. Including scientific viewpoints from as many different cultures as possible helps ensure that agreement isn’t the product of values rather than evidence. Over 80 national science academies around the world agree that humans are causing global warming. None disagree.

From Denial101x - National Academies of Science

Having a socially diverse consensus also guards against self-deception and outright fraud. Those with no stake in an outcome, or who stand to lose rather than gain from an outcome, reaching the same conclusion as those who might benefit increases our confidence that the conclusion is correct.

The consensus on climate shows clear Social Diversity.

Summary

When the pieces of the puzzle fit together and show the same picture, you have a Consilience of Evidence. When everyone is using the same standards of evidence and speaking the same language, you have Social Calibration. When agreement is widespread across many different groups of people with different backgrounds, you have Social Diversity.

When you have all three, you have a Knowledge-Based Consensus. And you can be confident that it’s correct. And this is what we have when it comes to the scientific consensus on human-caused global warming.

Resources and References

Consensus-related videos from Denial101x

Consensus of evidence - https://youtu.be/5LvaGAEwxYs

Consensus of scientists - https://youtu.be/WAqR9mLJrcE

Consensus of papers - https://youtu.be/LdLgSirToJM

Knowledge based consensus - https://youtu.be/HUOMbK1x7MI

Publications

Note: To read a more detailed article about a scientific consensus, please check out Scientific Consensus isn’t a “Part” of the Scientific Method: it’s a Consequence of it published on the Credible Hulk blog on August 9, 2017

Arguments

Arguments

Notions of "converging lines of evidence [sic]" could include "triangulation" as a concept.

This is indeed a helpful presentation.

A related thought would be that science is about education/learning, which is the pursuit of increased awareness and improved understanding. The consensus understanding is always being improved. However, the following quote from the “explainer” exposes how some scientific pursuits may impede the development and improvement of a consensus:

“Given the combative nature of science it’s highly unlikely that any scientist sets out to become part of a consensus.”

The “competition” between scientists can be helpful or harmful. Open collaboration is clearly the better way to pursue learning. Combative competition for wealth or status can produce negative results in many ways including:

A related understanding is that a very important sub-set of learning is "learning about what is harmful and the ways to limit harm done". Learning (science) aligned with the pursuit of limiting harm done is more sustainable. That is essentially the basis for the developed consensus understanding, open to continued improvement, of the Sustainable Development Goals.

That understanding leads to awareness that not everybody cares to govern their learning by the sub-set objective of limiting harm done. Other objectives can lead people to argue against a 'developing consensus understanding' in their pursuit ways to prolong or increase their ability to benefit from understandably harmful beliefs and actions.

I have only one recommendation for this important subject, use a heavier font style for webpage publication. Even with the typeface enlarged with the browser tool, it's still less than easily read by the visually impaired and older folks like myself.

myself. Link to the Credible Hulk article

[BW] Embedded link

This a really helpful reader for a non-specialist like myself. I suggest a tone-down, common language version and placing it on Wikipedia. At least on Wikipedia, its subject becomes documented for posterity. Besides, it's ready to go as is.

Search on Wikipedia

[BW] embedded link

To add another option to share this explainer, I created an audio version and put it up on Youtube: https://youtu.be/CQIowIu0yoc

This might come in handy whenever trying to explain a scientific consensus in YouTube comments where links to other videos work, but - at least for me - comments with links to other websites make them disappear immediately.

P.S.: Thanks to EddieEvans for giving me the idea to do this recording!