OA not OK part 4: The f-word: pH

Posted on 10 July 2011 by Doug Mackie

This is 4th post in our series about ocean acidification. Other posts: Introduction , 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, Summary 1 of 2, Summary 2 of 2.

Welcome to the 4th post in our series about ocean acidification. Confusion about pH is widespread, so we will use this post to remind readers about pH. Many people remember from school that pH is a measure of 'acidity', but not much more than that.

The original definition was that pH is the negative base 10 logarithm of the concentration of H+ ions (or, in a more accurate modern sense, H3O+ ions) in a solution.

But what does that mean?

Coverage of the 2011 earthquakes in New Zealand and Japan has reminded us that many people have a weak understanding of logarithms. Both the Richter scale (and its variants) and the pH scale are logarithmic. A base 10 logarithm (log) is the number, x, so that 10x gives the number you want. For example, the log of 100 is 2. This means that log(100) = log(10 x 10) = log(102) = 2. Similarly, the log of a million is 6, meaning that log(1,000,000) = log(10 x 10 x 10 x 10 x 10 x 10) = log(106) = 6 . The log of a number less than 1 is negative. For example, log(0.01) = log(1/100) = log(1/102) = log(10-2) = -2, compared to 2 for the log of 100.

Before ready access to calculators and computers, logarithms offered a convenient way to multiply large numbers. Now they are mostly used to compare numbers that differ by a very large relative amount.

For example, if we take the population of New Zealand (4 million), China (1340 million), and India (1270 million) then it can be hard to make comparisons, since the difference between China and India (70 million) is almost 20 x the population of New Zealand. But if we take the logs of the populations, New Zealand = 6.6, China = 9.13, and India = 9.10. It is now obvious that, relatively speaking, the populations of India and China are the same while that of New Zealand is very much less.

Earthquakes can range from feeling like a truck driving past to having the ground shaken like a dog with a toy. So to group earthquakes we use the Richter scale. A force 5 earthquake is 1000 times weaker than a force 8 because a log difference of 3 means 103 = 10 x 10 x 10 = 1000 difference. (There are lots of complications with earthquakes like energy vs. ground movement but let's ignore that for now).

H+ is never found by itself in a water based solution – it will always react with a H2O to form H3O+. So these days when chemists talk about pH they refer to H3O+ instead of H+ (which was in the original definition of pH and persists in some school text books). The definition of an acid (in aqueous chemistry) is thus a substance that gives (or donates) an H+ (proton) to water to form H3O+, while a base takes (or accepts) the proton. An acid is thus a source of H3O+.

The negative in the "–log" part of the pH expression is an artefact of convention: concentrations in pH calculations are much less than 1; so log values are negative. But, to avoid confusion by expressing a concentration as a negative number, the pH scale instead is multiplied by -1 to make all the numbers positive.

We are going to carry on pretending that it is this simple but, just for the record, the situation is, yet again, somewhat more complicated. (Chemists may wince, but we will avoid using 'activity' in these posts). However, we do need to introduce a chemical term: moles. A mole is the SI ('metric') unit for amount of substance. One mole of a substance is simply the molar mass in grams. For example, oxygen mass = 16 grams per mole, hydrogen mass = 1 gram per mole so the molar mass of water, H2O = 16 + 1+ 1 = 18 grams per mole. Therefore, 1 mole water = 18 g. Chemists use moles because the number of atoms or molecules in a mole is constant (1 mole = 6.022 x1023 atoms or molecules). Similarly, 1 mole of CO2 = 44 g and thus contains the same number of molecules (6.022 x 1023) as 18 g water. This is useful for chemists because they can use moles to look at reactions as if they were recipes - to bake a cake you need to know how many eggs you have, not the weight of the eggs.

You may recall from school that a pH of 7 is neutral. If we do the calculation we find that neutral water has an H3O+ concentration of 1 x 10–7 moles per litre (mol L-1). It isn't much, but it is definitely greater than zero. Where does the H3O+ come from? We mentioned the idea of equilibrium in post 1. The H3O+ comes from the reaction (called a dissociation) between two molecules of water:

Water does this naturally to a small extent, which means a water-based solution always contains a little H3O+. So, we define a neutral pH has the same concentration of H3O+ as pure water.

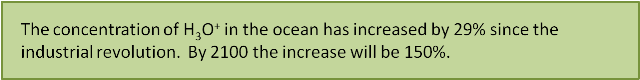

A difference of 1 pH unit means a 10x difference in the concentration of H3O+. Measurements (which we will talk about in post 11) show average ocean pH has decreased by 0.11 pH units (from 8.25 to 8.14) since the industrial revolution and is on track to decrease by a further 0.3 units (0.4 units in total, to 7.8) by 2100. Is that so bad? Yes. A difference of 0.11 pH units corresponds to a 29% increase in the concentration of H3O+. A difference of 0.4 pH units corresponds to a 150% increase in H3O+.

Try these calculations yourself. On a spreadsheet enter =10^-8.25 to calculate the pre-industrial concentration of H3O+ (on a calculator use the 10x button). In the next two cells enter =10^-8.14 and =10^-7.8. You have now calculated the pre-industrial, current, and predicted end-of-century concentrations of H3O+. The 29% increase in H3O+ can be verified by entering =100*(10^-8.14 - 10^-8.25)/(10^-8.25). Replace 8.14 with 7.8 (=100*(10^-7.8 - 10^-8.25)/(10^-8.25)) to check that the 0.4 pH unit difference (8.25 to 7.8) will lead to a 150% change.

In the next post we explain the concept of species in a chemical sense and introduce weathering.

Written by Doug Mackie, Christina McGraw , and Keith Hunter . This post is number 4 in a series about ocean acidification. Other posts: Introduction , 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, Summary 1 of 2, Summary 2 of 2.

Arguments

Arguments

0

0  0

0 second summary post

second summary post

Comments