Is Antarctica losing or gaining ice?

What the science says...

| Select a level... |

Basic

Basic

|

Intermediate

Intermediate

| |||

|

Antarctic sea ice extent has expanded at times but is currently (2023) low. In contrast, Antarctica is losing land ice at an accelerating rate and that has serious implications for sea level rise. |

|||||

Climate Myth...

Antarctica is gaining ice

"[Ice] is expanding in much of Antarctica, contrary to the widespread public belief that global warming is melting the continental ice cap." (Greg Roberts, The Australian)

At a glance

Who discovered the great, South Pole-straddling continent of Antarctica? According to the National Geographic, Captain Cook came within an estimated 80 miles of it in the late 1700s, but the three first 'official' discoveries all took place in 1820 by Russian, British and American teams of seafarers respectively.

Since that initial discovery, Antarctica has attracted and inspired researchers and explorers alike. It's a challenging place, fringed by sea-ice that, unlike the Arctic, has not steadily declined but whose extent fluctuates on a seasonal basis: it's currently (February 2023) at a very low coverage, but it can and does recover from such dips. Antarctic sea-ice is no great problem, with the exception of albedo-loss in low extent years: if it all melted, it would have no effect on global sea-levels. It's the stuff on land we need to focus upon.

The land of Antarctica is a continent in two parts, divided by the 2,000 m high Transantarctic Mountains. The two parts differ in so many respects that they need to be considered separately. East Antarctica, that includes the South Pole, has the far greater landmass out of the two, some 4,000 by 2,500 kilometres in size. Although its massive ice-sheet, mostly grounded above sea level, would cause 52 metres of sea level rise if it completely melted, so far it has remained relatively stable. Snow accumulation seems to be keeping in step with any peripheral melting.

In contrast, in the absence of ice, West Antarctica would consist of islands of various sizes plus the West Antarctic Peninsula, a long mountainous arm pointing northwards towards the tip of South America. The ice sheet overlying this mixed topography is therefore grounded below sea level in many places and that's what makes it far more prone to melting as the oceans warm up. Currently, the ice-sheet is buttressed by the huge ice-shelves that surround it, extending out to sea. These slow down the glaciers that drain the ice-sheet seawards.

The risk in West Antarctica is that these shelves will break up and then there will be nothing to hold back those glaciers. This has already happened along the West Antarctic Peninsula: in 1998-2002 much of the Larsen B ice-shelf collapsed. On Western Antarctica's west coast, the ice-sheet buttressing the Thwaites Glacier – a huge body of ice with a similar surface area to the UK - is a major cause for concern. The glacier, grounded 1,000 metres below sea level, is retreating quickly. If it all melted, that would raise global sea levels by 65 centimetres.

Such processes are happening right now and may not be stoppable - they certainly will not be if our CO2 emissions continue apace. But there’s another number to consider: 615 ppm. That is the CO2 level beneath which East Antarctica’s main ice sheet behaves in a mostly stable fashion. Go above that figure and the opposite occurs - major instability. And through our emissions, we’ve gone more than a third of the way there (320 to 420 ppm) since 1965. If we don’t curb those emissions, we’ll cross that line in well under a century.

Please use this form to provide feedback about this new "At a glance" section. Read a more technical version below or dig deeper via the tabs above!

Further details

Arguments that we needn't worry about loss of ice in the Antarctic because sea ice is growing or even that sea ice in the Antarctic disproves that global warming is a real concern hinge on confusion about differences between sea and land ice, and what our best information about Antarctic ice tells us.

As well, the trend in Antarctic sea ice is not a permanent feature, as we'll see. But let's look at the main issues first.

- Sea ice doesn't play a role in sea level rise or fall.

- Melting land ice contributes to sea level rise.

- The net, total behavior of all ice in the Antarctic is causing a significant and accelerating rise in sea level.

Antarctic sea ice is ice which forms in salt water mostly during winter months. When sea ice melts, sea level does not change.

Antarctic land ice is the ice which has accumulated over thousands of years in Antarctica by snowfall. This land ice is stored ocean water that once fell as precipitation. When this ice melts, the resulting water returns to the ocean, raising sea level.

What's up with Antarctic sea ice?

At both poles, sea ice grows and shrinks on an annual basis. While the maximum amount of cover varies from year to year, there is no effect on sea level due to this cyclic process.

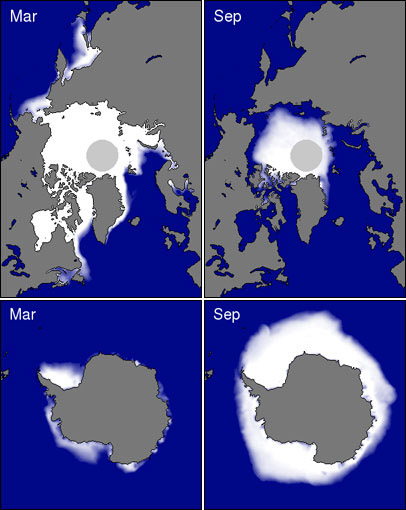

Figure 1: Coverage of sea ice in both the Arctic (Top) and Antarctica (Bottom) for both summer minimums and winter maximums. Source: National Snow and Ice Data Center

Trends in Antarctic sea ice are easily deceptive. For many years, Antarctic sea was increasing overall, but that shows signs of changing as ice extent has sharply declined more recently. Meanwhile, what's the relationship of sea ice to our activities? Ironically, plausible reasons for change may be of our own making:

- Ozone levels over Antarctica have dropped causing stratospheric cooling and increasing winds which lead to more areas of open water that can be frozen (Gillett & Thompson 2003, Thompson & Solomon 2002, Turner et al. 2009).

- The Southern Ocean is freshening because of increased rain and snowfall as well as an increase in meltwater coming from the edges of Antarctica's land ice (Zhang 2007, Bintanja et al. 2013). Together, these change the composition of the different layers in the ocean there causing less mixing between warm and cold layers and thus less melted sea and coastal land ice.

Against those factors, we continue to search for final answers to why certain areas of Antarctic sea ice grew over the past few decades (Turner et al. 2015).

More lately, sea ice in southern latitudes has shown a precipitous year-on-year decline (Parkinson 2019). While there's a remaining net increase in annual high point sea ice, the total increase has been sharply reduced and continues to decline.

How is Antarctic land ice doing?

We've seen that Antarctic sea ice is irrelevant to the main problem we're facing with overall loss of ice in the Antarctic: rising sea level. That leaves land ice to consider.

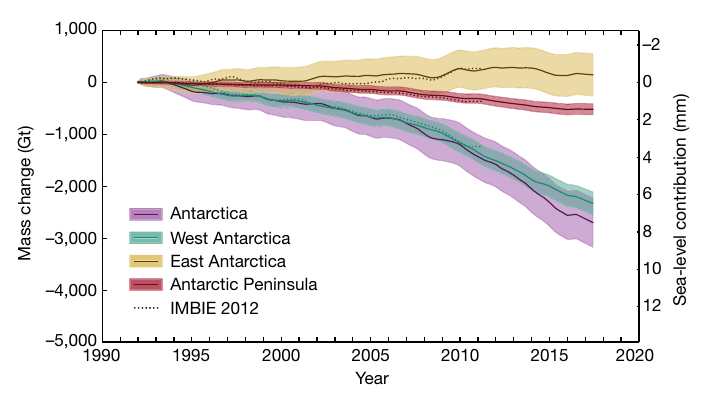

Figure 2: Total Antarctic land ice changes and approximate sea level contributions using a combination of different measurement techniques (IMBIE, 2017). Shaded areas represent measurement uncertainty.

Estimates of recent changes in Antarctic land ice (Figure 2) show an increasing contribution to sea level. Between 1992 and 2017, the Antarctic Ice Sheets overall lost 2,720 giga-tonnes (Gt) or 2,720,000,000,000 tonnes into the oceans, at an average rate of 108 Gt per year (Gt/yr). Because a reduction in mass of 360 Gt/year represents an annual global-average sea level rise of 1 mm, these estimates equate to an increase in global-average sea levels by 0.3 mm/yr.

There is variation between regions within Antarctica as can be seen in Figure 2. The West Antarctic Ice Sheet and the Antarctic Peninsula Ice Sheet are losing a lot of ice mass, at an overall increasing rate. The East Antarctic Ice Sheet has grown slightly over the period shown. The net result is a massive loss of ice. However, under a high-emissions scenario, ice-loss from the East Antarctic ice-sheet is expected to be a much greater in the decades after 2100, as reported recently by Stokes et al. (2022). That’s a scenario we must avoid at all costs.

Takeaway

Independent data from multiple measurement techniques (explained here) show the same thing: Antarctica is losing land ice as a whole and these losses are accelerating. Meanwhile, Antarctic sea ice is irrelevant to what's important about Antarctic ice in general.

Last updated on 14 February 2023 by John Mason. View Archives

Arguments

Arguments

The above was tail end of the conclusion of Zwally's presentation (I believe it was his presentation and not his paper), but anyway, my question is this; Is he correct in his statement that models predicted this increase in ice? I believe "Barry" even suggested that AR4 had similar predictions.

I'm not asking if his paper or his observations are correct, just the above statement. If it is correct, does this debunking need to be re-done?

"Is he correct in his statement that models predicted this increase in ice?" What he says is that models predict an increase in snowfall, and yes they do (going back to TAR I think). Warming in the southern ocean inevitably means more humid air moving into the interior of the Antarctica where it will fall as snow. The prediction was that this would increase the ice thickness in the interior (GRACE shows this happening). However, ice loss from the margins is so far outpacing that gain. These predictions were not about sea ice.

scaddenp,

So you are saying that antartica has a net loss of land ice. But you just said that back as far as TAR 1 that models were predicting a net gain in snow fall, but did they predict a loss of coastal ice? So which is it? That is the point of my last post. There seems to be some ambiguity here.

This whole thread is about how models and reality predict a loss in land ice, and that skeptics are confusing the gain in sea ice as proof of the failure of AGW.

So, again, do the models predict a gain or loss of land ice?

[JH] Please lose the tone. BTW, there is nothing precluding you from doing your own research on the issues you have raised.

Kevin,

Why does an increase in snowfall need to lead to an increase in land ice? And why would any increase in land ice need to remain as a constant, unchanging effect? A the same time, why do the models have to perfectly predict every reaction in a complex event never before seen by man? If the models got a single thing wrong, at some point in time, then that means all of climate change theory is wrong and we can just ignore it all?

I think you need to be more specific about what your questions (or criticisms) are. As it stands, your comment seems to demonstrate nothing but confusion about some pretty simple issues.

Kevin:

As far as I can see there is no ambiguity. The behaviour of Antarctic land ice along the coast is not the same as the behaviour of sea ice.

Composer99,

Here is the ambiguity.

That is a quote from the first assessment. It clearly predicts that there should be an increase in Land ice in Antartica. The SkS thread here says that there should be a decrease in Land ice. One of these predictions is obviously in error.

Kevin... Can you provide an actual link to that passage. The strange formatting and spelling make me question the source.

On first pass, other than the weirdness, it sounds like the passage is discussing snow accumulation rather than ice. But without a reference it's hard to know. Increased snow accumulation at higher altitudes has long been predicted and known.

The link is;

IPCC FAR link

It is the First assessment. Chapter 9, page 273.

This is not about high altitudes, this is about the antartic (which has a lot of land at high altitudes but..). The assessment is saying that there will be ice build up (snow build up - same thing as snow that gets piled on becomes ice) in the interior, with a net result of, a positive build up of ice through out antartica, not a loss.

The SkS thread clearly states that there will be a net loss, so again, clearly something is amiss.

[RH] Fixed link that was breaking page formatting.

Rob,

Here's the link to the chapter from the First Assessment Report, published in 1990. The reason for the typos is that the PDF online is a scan (image), not text, so it had to be transcribed. See section 9.4.5, and as usually, read the entire thing, not just the cherry-picked section chosen by a denier for a quote... particularly things like the opening line ("The question of the balance of the Antarctic ice sheet proves to be a very difficult one from a physical point of view...") and later ("It must be stressed that the inference of ice mass discharge from a limited number of surface velocity measurements involves many uncertainties."). The quote in question is on page 273.

So Kevin's complaint appears to be that in 1990 (23 years ago) scientists did not perfectly understand and predict exactly what would happen a quarter of a century later as a result of climate change. And we should "update" the current rebuttal to properly reflect what scientists didn't perfectly understand 23 years ago.

[You just can't make this stuff up.]

Rob Honeycutt - That passage apears to be from the 1990 IPCC FAR report, chapter 9, page 27.

Kevin - Two notes. First, list your references.

Second, do you honestly think that the science wouldn't be updated in the last 23 years? Sea level contributions and cryosphere mass balance are still under investigation, and cryosphere contributions to sea level are still at a somewhat lower certainly in the 2007 AR4 report. Not to mention that the last 23 years of warming will have changed the situation somewhat.

Current measures (including GRACE mass measures) indicate a net loss of Antarctic land ice. Mass balance includes both accumulation (increased snowfall due to higher absolute humidities) and loss (increased melting at the coasts due to warmer sea water). Snowfall can increase and Antarctica still lose mass, because there are two terms to that balance.

Yup. Just reading through it. It's all relative to sea level changes. What's particularly interesting to me (and encouraging) is that the report isn't overstating their confidence levels. They're using very careful wording to accurately convey what they knew at that time. If you read on, they're also talking about the instability of the WAIS. Clearly, you can be adding ice (snow) in the interior but also be losing ice through ablation. And that is what I've always read in the literature. I'm not seeing the FAR chap 9 disagreeing with this at all.

I could not find an actual prediction regarding antartic ice sheet levels in the fourth assessment (they do discuss the peninsula). They do, however, in the openning comments address the projections of the TAR as indicated below.

It is interesting that this is not sea ice they are talking about, but land ice.

So Sphaerica, has the science advanced enough for the fourth (actually third) assessment? If not, then I guess they have no business commenting on anything. The Third assessment was saying that snow gains more than covers coastal losses.

I would also add that the passage cited by Kevin is not a prediction (contrary to his assertion), but a description of observed contemporary ice sheet behaviour, of Antarctica as a whole, up until the publication of FAR, while the discussion in the OP has to do with observed (not predicted) behaviour in the last decade (as per the publication dates of papers cited), so there is little surprise that the OP mentions more ice mass loss than FAR.

Finally, scaddenp mentioned the Third Assessment Report, in 2001, whose descriptions of observed behaviour in Antarctica would differ from the observed behaviour described in the 1990 FAR and also from the behaviour discussed in the present day.

Kevin, was it your intent to suggest that:

(Clarification to my post #172: it does not include any comments posted by Kevin in #171.)

From the Scenarios of future change, 16.1.4 of the Third assessment report...

And yes, there is extensive uncertainty in this prediction, as some processes are not understood entirely.

Bottom line though, the latest prediction by the IPCC has Antartica Land Ice gaining as temps increase.

Kevin,

The bottom line is that you don't understand what it is that you are reading, and you are projecting that ignorance onto everyone else.

The Antarctic Ice Sheet is a complex environment, consisting of an interaction between rising temperatures, increasing precipitation, ice at extreme altitude (hence always below freezing), ice just above sea level (affected by air temperature), ice below sea level (affected by the warming water beneath), and gravity (which threatens to flow ice gains in the interior quickly down into the ocean, where it will melt). This now is recognized to be further complicated by the freshening of the surrounding ocean water due to the melt, changes in currents, etc.

And out of all of this, your takeaway is that the IPCC reports have some comments that you can cherry-pick to raise false doubt.

This is why the term "denier" is used at all.

Bottom line: You don't understand what you are reading, and you are going out of your way to create an illusion of doubt and incompetence, because you can't come to terms with the idea that your actions (and lack of action) are going to affect future generations, and you maybe will need to demonstrate more responsibility (and yes, maybe a little sacrifice) when you don't want to.

I am always appalled at the way my generation lauds The Greatest Generation for the great sacrifices they were repeatedly able to make... and yet they won't surrender their multi-ton SUVs until you pry them from their baked, dead hands.

[JH] Please tone down the judgemental rhetoric. We simply do not know whether Kevin posts to cause mischief, or is honestly trying to understand a very complex subject matter. Kevin has also been advised to tone down his posts.