How reliable are climate models?

What the science says...

| Select a level... |

Basic

Basic

|

Intermediate

Intermediate

| |||

|

Models successfully reproduce temperatures since 1900 globally, by land, in the air and the ocean. |

|||||

Climate Myth...

Models are unreliable

"[Models] are full of fudge factors that are fitted to the existing climate, so the models more or less agree with the observed data. But there is no reason to believe that the same fudge factors would give the right behaviour in a world with different chemistry, for example in a world with increased CO2 in the atmosphere." (Freeman Dyson)

At a glance

So, what are computer models? Computer modelling is the simulation and study of complex physical systems using mathematics and computer science. Models can be used to explore the effects of changes to any or all of the system components. Such techniques have a wide range of applications. For example, engineering makes a lot of use of computer models, from aircraft design to dam construction and everything in between. Many aspects of our modern lives depend, one way and another, on computer modelling. If you don't trust computer models but like flying, you might want to think about that.

Computer models can be as simple or as complicated as required. It depends on what part of a system you're looking at and its complexity. A simple model might consist of a few equations on a spreadsheet. Complex models, on the other hand, can run to millions of lines of code. Designing them involves intensive collaboration between multiple specialist scientists, mathematicians and top-end coders working as a team.

Modelling of the planet's climate system dates back to the late 1960s. Climate modelling involves incorporating all the equations that describe the interactions between all the components of our climate system. Climate modelling is especially maths-heavy, requiring phenomenal computer power to run vast numbers of equations at the same time.

Climate models are designed to estimate trends rather than events. For example, a fairly simple climate model can readily tell you it will be colder in winter. However, it can’t tell you what the temperature will be on a specific day – that’s weather forecasting. Weather forecast-models rarely extend to even a fortnight ahead. Big difference. Climate trends deal with things such as temperature or sea-level changes, over multiple decades. Trends are important because they eliminate or 'smooth out' single events that may be extreme but uncommon. In other words, trends tell you which way the system's heading.

All climate models must be tested to find out if they work before they are deployed. That can be done by using the past. We know what happened back then either because we made observations or since evidence is preserved in the geological record. If a model can correctly simulate trends from a starting point somewhere in the past through to the present day, it has passed that test. We can therefore expect it to simulate what might happen in the future. And that's exactly what has happened. From early on, climate models predicted future global warming. Multiple lines of hard physical evidence now confirm the prediction was correct.

Finally, all models, weather or climate, have uncertainties associated with them. This doesn't mean scientists don't know anything - far from it. If you work in science, uncertainty is an everyday word and is to be expected. Sources of uncertainty can be identified, isolated and worked upon. As a consequence, a model's performance improves. In this way, science is a self-correcting process over time. This is quite different from climate science denial, whose practitioners speak confidently and with certainty about something they do not work on day in and day out. They don't need to fully understand the topic, since spreading confusion and doubt is their task.

Climate models are not perfect. Nothing is. But they are phenomenally useful.

Please use this form to provide feedback about this new "At a glance" section. Read a more technical version below or dig deeper via the tabs above!

Further details

Climate models are mathematical representations of the interactions between the atmosphere, oceans, land surface, ice – and the sun. This is clearly a very complex task, so models are built to estimate trends rather than events. For example, a climate model can tell you it will be cold in winter, but it can’t tell you what the temperature will be on a specific day – that’s weather forecasting. Climate trends are weather, averaged out over time - usually 30 years. Trends are important because they eliminate - or "smooth out" - single events that may be extreme, but quite rare.

Climate models have to be tested to find out if they work. We can’t wait for 30 years to see if a model is any good or not; models are tested against the past, against what we know happened. If a model can correctly predict trends from a starting point somewhere in the past, we could expect it to predict with reasonable certainty what might happen in the future.

So all models are first tested in a process called Hindcasting. The models used to predict future global warming can accurately map past climate changes. If they get the past right, there is no reason to think their predictions would be wrong. Testing models against the existing instrumental record suggested CO2 must cause global warming, because the models could not simulate what had already happened unless the extra CO2 was added to the model. All other known forcings are adequate in explaining temperature variations prior to the rise in temperature over the last thirty years, while none of them are capable of explaining the rise in the past thirty years. CO2 does explain that rise, and explains it completely without any need for additional, as yet unknown forcings.

Where models have been running for sufficient time, they have also been shown to make accurate predictions. For example, the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo allowed modellers to test the accuracy of models by feeding in the data about the eruption. The models successfully predicted the climatic response after the eruption. Models also correctly predicted other effects subsequently confirmed by observation, including greater warming in the Arctic and over land, greater warming at night, and stratospheric cooling.

The climate models, far from being melodramatic, may be conservative in the predictions they produce. Sea level rise is a good example (fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Observed sea level rise since 1970 from tide gauge data (red) and satellite measurements (blue) compared to model projections for 1990-2010 from the IPCC Third Assessment Report (grey band). (Source: The Copenhagen Diagnosis, 2009)

Here, the models have understated the problem. In reality, observed sea level is tracking at the upper range of the model projections. There are other examples of models being too conservative, rather than alarmist as some portray them. All models have limits - uncertainties - for they are modelling complex systems. However, all models improve over time, and with increasing sources of real-world information such as satellites, the output of climate models can be constantly refined to increase their power and usefulness.

Climate models have already predicted many of the phenomena for which we now have empirical evidence. A 2019 study led by Zeke Hausfather (Hausfather et al. 2019) evaluated 17 global surface temperature projections from climate models in studies published between 1970 and 2007. The authors found "14 out of the 17 model projections indistinguishable from what actually occurred."

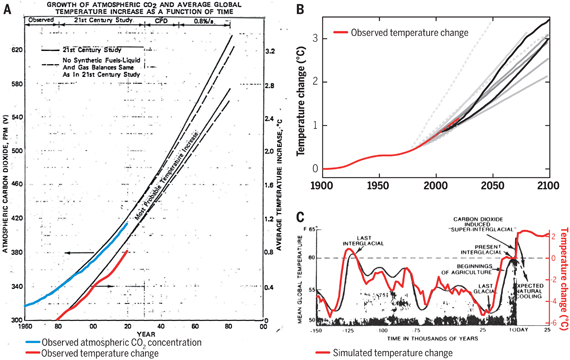

Talking of empirical evidence, you may be surprised to know that huge fossil fuels corporation Exxon's own scientists knew all about climate change, all along. A recent study of their own modelling (Supran et al. 2023 - open access) found it to be just as skillful as that developed within academia (fig. 2). We had a blog-post about this important study around the time of its publication. However, the way the corporate world's PR machine subsequently handled this information left a great deal to be desired, to put it mildly. The paper's damning final paragraph is worthy of part-quotation:

"Here, it has enabled us to conclude with precision that, decades ago, ExxonMobil understood as much about climate change as did academic and government scientists. Our analysis shows that, in private and academic circles since the late 1970s and early 1980s, ExxonMobil scientists:

(i) accurately projected and skillfully modelled global warming due to fossil fuel burning;

(ii) correctly dismissed the possibility of a coming ice age;

(iii) accurately predicted when human-caused global warming would first be detected;

(iv) reasonably estimated how much CO2 would lead to dangerous warming.

Yet, whereas academic and government scientists worked to communicate what they knew to the public, ExxonMobil worked to deny it."

Fig. 2: Historically observed temperature change (red) and atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration (blue) over time, compared against global warming projections reported by ExxonMobil scientists. (A) “Proprietary” 1982 Exxon-modeled projections. (B) Summary of projections in seven internal company memos and five peer-reviewed publications between 1977 and 2003 (gray lines). (C) A 1977 internally reported graph of the global warming “effect of CO2 on an interglacial scale.” (A) and (B) display averaged historical temperature observations, whereas the historical temperature record in (C) is a smoothed Earth system model simulation of the last 150,000 years. From Supran et al. 2023.

Updated 30th May 2024 to include Supran et al extract.

Various global temperature projections by mainstream climate scientists and models, and by climate contrarians, compared to observations by NASA GISS. Created by Dana Nuccitelli.

Last updated on 30 May 2024 by John Mason. View Archives

Arguments

Arguments

I have a question on model reliability in predicting arctic sea ice. I just read (parts of) "Constraining projections of summer Arctic sea ice" by Massonnet et al. Looking at their figure 1, it is clear that most CMIP5 models do not accurately model

past september sea ice extent (SSIE). This is even more visible in their figure 2, which shows that 90% of the models either simulate an average SSIE in

1979-2010 outside of 2 sigma of the actual average, or a trend in SSIE outside of 2 sigma of the actual trend. If the physics of the models were perfect, only 10% of model runs would be expected to fall outside this window.

To my mind, this shows that the models still miss essential physics, and it would be unwise to attribute too much predictive power to them. A linear trend may be a better predictor. Yet, I never hear a scientist say 'The models aren't good enough at the moment, so it may be wiser to look at the linear trend.'

Why is that?

Is there a fundamental discussion somewhere on the relative merits of a linear trend versus a model as a predictor of the future?

@bouke The fact that the models are obviously missing some physics that is important for regional (i.e. Arctic) climate does not imply that they are not useful for global climate projection, for the simple reason that the missing physics is only relevant to a particular region, and hence this doesn't substantially affect the global climate.

Scientists are perfectly happy to discuss the flaws in the models, however the reason they don't often explicitly say that "the models aren't good enough" is because it isn't an all-or-nothing issue. There are some things the models predict well, and others that they don't.

The main reason they use models rather than linear trends on the other hand has nothing to do with predictive power. A physical model allows you to test the consequences of a set of assumptions of how the physics of climate works. A linear trend is just a statistical model based on correlations and does not allow you to draw any causal conclusions.

I doubt there is a fundamental discussion on the relative merits of the two approaches for the simple reason that they are two tools with different jobs. Secondly a linear model is only appropriate for a situation where the (rate of change) of the forcings are approximately constant, which is unlikely to be true of centennial scale projections for which physical models are more appropriate.

The 'intermediate' article for this topic notes that Arctic Sea ice decline and global sea level rise models have proven to be very conservative in comparison to actual results.

The reasons for this are also generally known... scientists have only recently begun to get a handle on the rate of ice loss from Greenland and Antarctica and thus these were excluded from sea level rise models. Now that we know that there is significant ice loss going on that will be factored in to the models and they will move closer to the observed values. Similarly, recent findings have shown that mechanical effects (i.e. ice breaking up under wind), bottom melt due to unexpected circulation patterns, ice export, and other significant factors were not included in the Arctic ice loss models.

This does not mean that all climate models are similarly lacking important factors. The atmospheric temperature models have been largely on target. The PIOMAS Arctic ice volume model has been confirmed by recent sattelite measurements. Et cetera.

No model includes the wing flaps of every butterfly on the planet, but we have a pretty good idea of which models include major uncertainties and which do not. Also, contrary to what you say, it is very common for linear (and other) trends to be used when looking at various climate factors. Indeed, a linear trend is a model... just a very simple one. Search on Maslowski or Neven for examples of this pertaining specifically to Arctic sea ice. Their trend projections show sea ice extent dropping to near zero in the next few years.

bouke,

First, for reference, readers can look at the two figures that you reference. In each figure, the black line/square represents the NSIDC observed value, while the colored lines/squares represent the values resulting from various model ensembles. The first graph is of 5-year running mean September sea ice extent, while the second cross references the1979-2010 mean and trend (the observed value is in the center of the 2-sigma black box, and the average of all of the models is shown as an orange cross).

Note that these figures focus on the September mean. They show nothing concerning the September minimum or the overall flux of ice of the course of the year. They also show extent, not area or volume. As such, the main question one must ask is "how does this short lived model discrepency affect overall global mean temperature within the model." In particular, it should be noted that most models overestimate the ice extent, especially in relation to the recent plummet, and so most models are most likely underestimating the expected feedback (with respect to Arctic ice extent) in recent years.

Figure 1:

Figure 2:

Your question conflates any number of false assumptions.

First, let me point out that the existence of this flaw in the models is first and foremost excellent evidence against the silly denier's misunderstanding that models are "tweaked" and "parameterized" to produce a particular result. This is not the case. The models are based on physics, and the only valid way (in most cases) to adjust the model is to refine the physics to bring the final result more in line with observations.

With that said, one of the first issues with comparing models to observations is the quality of the observations. In the case of sea ice extent, there is a lot of wiggle room for how one computes the extent... how much of a "pixel" of sea area do you count as ice or open water? You can use this page to view some of the various methods all at once. There is a fair spread in the values of the various methods within observations. Why then would you not expect a spread in the model estimates?

Secondly, and this is the more important point, the number of factors in the models is huge. You've picked one and said it doesn't work, so throw out the models and substitute the most unphysical thing you can imagine, a linear trend -- which in turn is the ultimate in parameterization. Such a false dichotomy is absurd. This is rather like complaining that some people die in car crashes, so until no one dies in a car crash, cars are too unsafe to drive and everyone should walk everywhere.

Thirdly, you are missing the point of the climate models, and you present a strawman before your question ("it may be wiser to look at the linear trend"). Look at the linear trend for what? Sea ice prediction? Global mean temperature? For what reason? To evaluate the climate system, or to address policy issues?

The climate models exist first and foremost to study the climate. Scientists will know they have Arctic sea ice modeled very well when they start to fall within that 10% range you discuss, but honestly, I don't think that will ever happen, because at the current rate the ice will be completely gone before they've figured out what is innaccurate within the models. Then they can just cut sea ice out of the picture.

Climate models have another value in being one predictor of climate sensitivity. The linear trend that you suggest would need to be based on something. Observations? The flaw there is that we only have a very short time span to use as a basis. Paleo-studies? Very valuable, but also very constrained by the inference of "observations" through indirect means.

In the end, however, what we do see is that the estimates for climate sensitivity from a very wide variety of models, observations, paleostudies and other methods all converge in the same 2˚C to 4.5˚C range. This tells us that, despite individual flaws within the models, the overall answers are pretty darn good.

Lastly, I would point out that people have long been pointing to the plunge in Arctic ice, and the discrepency in the models, in that the Arctic ice is failing far faster than anyone ever imagined possible. I do wish that the modelers would redirect their attentions to that sphere, and figure out whe the models are so far off in that respect.

But, as I've already said, there may be little value in that. It might be that heat transport under the ice is far greater than expected. It may be that additional factors such as black soot and altered weather patterns have a greater influence than expected. It may be that summer water runoff from North America and Siberia has a far greater influence on sea surface temperatures and salinity. It may be that the polar amplification of warming is even worse than expected (something that is difficult to perfectly measure, since most global mean temperature analyses are sparse in the polar regions).

But whatever the reason... I'm pretty sure that the Arctic is going to be ice free for large parts of the summer and fall long before the modelers get around to understanding all of the physics behind the particular details of Arctic ocean currents and ice, and the Arctic will have become such an alien environment that that entire part of the models will more easily be replaced with a very, very simple linear trend... a flat line centered on zero.

@Sphearica, Dikran, CBDunkerson: You misunderstand me. I don't have a problem with climate models, I just thought this was the most appropriate place to ask my question. It is narrowly about SSIE, and I understand that it does not generalize to other output parameters of models. I guess I should have qualified my "it would be unwise to attribute too much predictive power to them" with "regarding SSIE".

The issue I have is that I see scientists making predictions on the basis of their models. Those predictions will be used as the basis for policy, so they should be as accurate as possible. At the moment, a case can be made that simple statistics (or very simple models, if you like) are more accurate than these models regarding SSIE. I am missing that fact in the scientific discourse.

I just read the leaked AR5 on the matter (paragraph 12.4.6.1), and it does not touch linear trends at all. The probable reason for that is that there are no papers on it, which in turn is because it is hard to present a new scientific result on just a simple linear trend. The result is that the AR5 is missing a piece of analysis that should have been present, IMHO.

Btw, I read Neven's blog, so I know what these trends look like: ice free around 2020. A little earlier if you take PIOMAS volume, or an exponential fit, a little later if you take sea ice extent, or a linear fit. According to AR5, the best estimate for RCP4.5 is 2035–2065. There's an unexplained discrepancy there, IMHO.

@Sphearica specifically: I am a bit surprised at your tone. I understand that you thought that I claimed that model problems regarding SSIE disqualified models altogether, which would indeed be a grandiose claim. The logical fallacy in this case would be Hasty Generalization. However, the things you mention, "false assumptions", "false dichotomy", "strawman", I really don't see in my post. I don't really think that using such strong words is helpful.

bouke: Maslowski, et al 2012

Bouke wrote: "The issue I have is that I see scientists making predictions on the basis of their models. Those predictions will be used as the basis for policy,"

Exactly what are the policy decisions that are being made based on predictions of SSIE?

bouke,

I'll give you a half-apology, if in fact your question was innocent and genuine, but I've reread it several times, and it strikes me as part concern-troll, part denier-mythology. You make a lot of broad-brush statements, dripping with doubt, like "I never hear a scientist say..." and "Why is that?" and "The issue I have is that I see scientists..." — as if your role as armchair-jurist is to judge how well scientists are doing their jobs, and your neighbor told you they aren't.

You read one paper, and then drew a bunch of unjustified conclusions. I suspect that much of your interpretation is tainted by the uneducated comments you may have seen on other sites, and if that is the case, I'd suggest that you follow up such comments with solid research to confirm their validity.

In particular I would suggest that you follow the following Google Scholar search and see what you can infer from the actual work that is being done by scientists, rather than hobby-site comments and a single paper:

@CBDunkerson

Interesting, I didn't know about that.

@Dikran

The current policy decision is to do nothing, more or less. If, when AR5 comes out, it contains an earlier possible date for an ice free summer, initiatives like this (met-office-investigating-arctic-link-in-record-low-temperatures)

would gain in urgency. I think that would be a good thing.

@Sphaerica

It is very hard to convey irony and things like that through text alone. My personal strategy to combat miscommunications is to remove as much rhetorics as I can: If I ask a question, it is because I want to know something. If I consciously make an assumption, I state that. If I make a statement of fact, I am very careful that I'm sure its true. Unfortunately, this sometimes makes posts difficult to distinguish from concern trolls, but I don't really know a way to avoid that.

You wrote 'You read one paper, and then drew a bunch of unjustified conclusions'. I read more than one paper, and haven't drawn many conclusions yet. I could go on a rant that it is actually you who is drawing unjustified conclusions, but such a thing would be a rhetorical trick, and as such unproductive. I don't want to go there.

Perhaps I should tell something about were I'm coming from. I get my information from skeptical science, realclimate.org, occasionally papers (it takes a lot of energy to read them), youtube recordings of scientists presenting their work, 'the discovery of global warming' (http://www.aip.org/history/climate/index.htm). When I am tempted to tell myself I know something for a fact, I seek out information from sources that say the opposite. When I detect that those sources contain lies of omission, or just plain lies, my confidence goes up. When those sources contain interesting new insights, I learn something.

Currently, I am tempted to conclude that the scientific consensus, as represented in AR5, is too conservative regarding SSIE. There's been research that shows that the IPCC is too conservative more often than too alarmist, so that increases my confidence that this may indeed be the case here. I ask myself how this could happen, and one hypothesis is that scientists are in the business of understanding things, not in the business of predicting things. Current understanding (i.e. the current models) isn't good enough to make good predictions. Nevertheless, generally, only those predictions are publicized, and so only those predictions end up in AR5.

Something like an expert elicitation study for sea ice could shed some light on my question, but I don't know if they exist for sea ice.

@Bouke, it is a pity that you dodged my question. You suggested that the lack of skill in the models is an issue as they are used to decide policy. You also clarified that the lack of skill you mentioned was specific to sea ice extent (your post 610). However there are no policy decisions that rest on prediction of sea ice extent, which reveals that you concerns are baseless.

You claim that your aim is to remove as muich rhetoric as possible. I would suggest you start by avoiding the sort of evasion in which you have just engaged and in future give direct answers to direct questions.

Please try again: "Exactly what are the policy decisions that are being made based on predictions of SSIE?" if the answer is "none", then please say so explicitly.

@Dikran

Agreed. Well, sea ice extent minimum to be more precise.

Disagreed. Firstly, I think 'rest on' is too strong a wording for the conclusion you are trying to make. It is enough for a policy decision to be influenced by the prediction, to make my concerns not baseless.

Secondly, perhaps we disagree on what constitutes a policy decision. I think doing nothing about a (perceived) problem is an actual policy decision, equally valid as doing something. It may be the best policy decision, actually. But I guess you want specifics of policy decisions that are not taken.

"To fund research to study changes in weather patterns as a consequence of a seasonally ice free arctic" is a policy decision. The current policy is not to spend the money. I think this decision is influenced by the prediction of sea ice extent minimum.

"To limit CO2 emissions to a specific target" is a policy decision. One of the political parties in my country (the VVD) say they have a CO2 emissions target, but they don't spend funds or propose regulation to achieve this goal. In effect, they are doing nothing. I think this decision is influenced by the prediction of sea ice extent minimum. I think the influence is small, but real. If a consequence of climate change may be right around the corner, it becomes less defensible to do nothing.

@bouke O.K. substitute "are substantially influenced by" for "rest on": "What policy decisions are substantially influenced by predictions of sea ice extent?"

I agree that "do nothing" is a policy decision, nothing I wrote suggests otherwise. Funding projects on changes in weather patterns due to changes in Arctic sea ice extent on the other hand is not a policy decision (grants are awarded competitively and are effectively selected by peer review, although there are also calls for proposals on particular topics). However, this is still not a decision where deficiencies in the models has any real impact on the decision as the observations are perfectly clear, so again it doesn't support your stated concern.

"To limit CO2 emissions to a specific target" IS a policy decision, but is not one where model projections of Arctic sea ice extent have big impact for the simple reason that the reason for the limit on CO2 is to limit the effects of GLOBAL climate change. Arctic sea ice at this point is essentially history more or less no matter what we do to limit CO2, so anybody arguing that CO2 should be limited to save Arctic sea ice extent has pretty much missed the boat.

Essentially the point is that for Arctic sea ice extent, the observations tell you what is happening, the models predict that the Arctic sea ice will last longer than the observations suggest to the extent that we know that their projections are wrong, and hence nobody should be taking them sufficiently seriously as a basis for policy.

Now you think that they do have an effect on policy, but do you have any evidence to support that?

@Dikran

The only way I could reconcile (3) with (2) was if you didn't consider doing nothing a policy decision. That's where (4) came from.

The entire purpose of the IPCC is to inform policymakers. The IPCC's AR5 draft mostly discusses models and their projections. If you think that the projections of those models are wrong, why are these projections in AR5?

Anyway, this is the last post by me on this matter. I will read answers but won't post more. Except for CBDunkersons link, the discussion here hasn't been very useful for me and I doubt that will change.

@bouke The current policy decision to do nothing [and it is a policy decision] is not based on the projections of sea ice extent, so you did dodge the question.

I'm sorry, I have better things to do with my time than engage in evasive rhetorical discussions. If you want to demonstrate that is not what you are trying to do, then give a cogent explanation of how sea ice extent projections support the policy decision to do nothing. The models clearly indicate that sea ice extent is diminishing and that we will see effectively ice free summers on a timescale relevant to human lives, so even though they underestimate the rate of ice loss, the clearly argue that we should do something, not do nothing.

Stealth (on another thread) wrote "I would love to examine the source code of some GCMs to see if Dr. Freeman Dyson’s claim that GCMs are full of fudge factors is true. I suspect that it is true because software modelers always have to make assumptions and design trades in order to get software to run in a reasonable amount of time."

Stealth, Freeman Dyson has no idea what is in climate models, as he himself has publicly admitted. For some reason he is comfortable admitting he knows nothing about climatology but in the same conversation stating his admittedly baseless speculations as if he is absolutely confident they are facts.

Probably what Dyson meant by "fudge factors" were parameterizations, which are not merely fudge factors. RealClimate has short explanations of parameterizations in its FAQ on Climate Models Part II.

Regarding the overall quality of the software engineering aspects of models: No software is perfect (not even software for controlling spacecraft), but good software is good enough for the purposes it is put to. Determining whether software is sufficiently good is a process called verification and validation (V&V). Climate models do go through V&V. The type of V&V must be appropriate to the type of software and the contexts of its construction and use. The same is true of V&V of climate models, as Steve Easterbrook explained; Steve used to do V&V for NASA software.

But the real test of GCMs' adequacy is in their ability to predict, which is quite good at the time scales they are expected to predict well. The forcing and feedbacks interact to produce temperature changes that bounce up and down. Those changes in periods of less then 30 years are called "weather," but those short-term weather changes average out across periods of 30 years or more, so 30 years is approximately the definition of "climate." Weather is not climate, so predicting weather is not the same as predicting climate. Weather, especially in small geographic areas, is nearly impossible to predict more than a week in advance, but climate, especially for large geographic areas such as the entire globe, is and has been successfully predicted decades in advance--notably by Arrhenhuis in the 1890s, with more fine tuning in each generation of model, for example by Hansen in 1988, and with increasing accuracy with each improvement in the models. The accuracy is most evident in graphics if you properly position the observed temperature line at its mean trend at the start of the graph, as explained with the last three figures in a post by Tamino.

Stealth, on another thread:

KR @ 248: I get the impression that you do not understand physics; fudge factors are not an accusation of fraud in any way. The comment of “fudge factors” is from Dr. Freeman Dyson, a world renowned physicist -- I am certain he is qualified to speak to both physics and fudge factors.

But he is not qualified to speak on models, as Tom Dayton showed, and your original use of the phrase "Dyson's claim that GCMs are full of fudge factors" didn't sound like an innocuous use of physics jargon.

As an example, in the CO2 forcing equation, ΔF = 5.35*ln(C/C0) W/m2, the 5.35 value is a “fudge factor”, and so is the natural logarithm function. Over a much larger sample of data, for example, a logarithm with a base of pi may fit better than one with a base of e. [Emphasis mine.]

Erm... You may want to rethink that.

The “laws of physics” are not something given to us from on high. They are simply a mathematical representation of what we think is happening, or a way to describe how something behaves.

They embody our understanding of physical reality. If you are going to base your arguments on ignoring the laws of physics on the basis that they may not be correct, it's only fair to say so. It's important to be able to give "models" that are based on what we don't think is happening the weight they deserve.

Your statement of “They are full of physics” as a way to assert truth or correctness of the models, is both meaningless and ignorant.

What he means is that they embody our understanding of physical reality. That's hardly meaningless and ignorant.

Some of the other folks here are a little combative or condescending.

Sorry about that. I get a bit testy when someone expresses doubt that they can get hold of the source code of the models when they obviously haven't attempted to do so, then when pointed to the correct location to download the source code proclaim that they've wasted enough time trying and question whether those who gave links have actually attempted it themselves, while finding time to twist statements that they found "interesting" to mean other than what was intended. As the steps I gave showed, it was hardly an onerous exercise.

All the while not admitting that the accuracy of the coefficient 5.35 is actually far higher than suggested earlier.

This is what I mean when I say “all models are wrong.” This doesn’t mean they are not useful

You're hardly the first to make that observation.

but it means they are limited in their effectiveness because of the underlying assumptions. How GCMs handle this effect is critical across every equation they use. My primary concern is that almost every equation in GCMs have various limitations or assumptions because they are calibrated to measurements made recently.

Firstly, GCMs aren't parameter-fitting statistical models that are simply fitted to recent observations. Where parameterisation is performed, it is at a low level and it is based on observation of the particular physical process in question. The fact that, when combined, the model as a whole actually reproduces the observed record extremely well (and is unable to when anthropogenic influences are removed) is a testament to the model's accuracy.

Secondly, no matter how complicated the model, and no matter how many "fudge factors" are involved, at the end of the day the model still has to satisfy some pretty basic physics. This is why a simple energy balance model can reproduce the temperature record remarkably well, even though it cannot tell you what the regional effects will be, or changes to ocean circulation, or Arctic sea ice. These limit its accuracy but there are still some pretty strong bounds on the possible behaviour of the more sophisticated models.

JasonB @258: I followed your instructions and still failed. Trying to extract the ModelE1 tarball using Windows and WinZIP fails.

My instructions were to use 7-zip, not WinZIP. I'm surprised that someone with your experience developing software was stumped by a .tar.gz file.

So now I have actual Fortran code for a 10 year old model.

Well, what did you expect? That's the source code for one of the models that was used to create the forecasts for the still-current IPCC report. You want to check those forecasts, you look at the source code for those models. It's also an ancestor of one of the models used for the next IPCC report.

[TD] Thank you for replying on an appropriate thread!

Many of the issues being dicussed on this thread are addressed in the article,

Seeking Clues to Climate Change: computer models provide insights to Earth's climate future, Science & Technology Review, June 2012, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

I have had some conversations with Richard Moore, who says,

"The warming we have experienced is real, but it is not unusual, it is not alarming, and it bas nothing to do with CO2. What I'm looking for is an intelligent response to my analysis:"

rkmdocs.blogspot.ie/2010/01/climate-science-observations-vs-models.html

I find it a bit too detailed to get the gist of what he is saying. Does anyone have the time to comment on it?

Thanks,

...Alan James

alan_james@handshake.ca

acjames76 - I have replied on the more appropriate It's not us thread.

[TD] Thank you for thread-herding!

The thing about the models that is screwing it up now is the divergence with solar and CO2, which had always been closely linked. No the solar is backing off, and the mistaken notion that a high solar level isn't enough (it is), an ever incresing one being needed (false), is showing the pundits they hooked their cart to the wrong horse. The solar has been and still is the driver. All those folks who put CO2 in charge are just waiting for the trend to go up again. Good luck folks. When the solar activity returns to warming levels it will go up again. Til then you are out of luck. The math of the models is flawed and the flaw is showing. It did great when solar and CO2 were in lockstep (the past), but picked the wrong driver and is now showing the error big time.