Is the science settled?

What the science says...

| Select a level... |

Basic

Basic

|

Intermediate

Intermediate

| |||

|

That human CO2 is causing global warming is known with high certainty & confirmed by observations. |

|||||

The science isn't settled

"Many people think the science of climate change is settled. It isn't. And the issue is not whether there has been an overall warming during the past century. There has, although it was not uniform and none was observed during the past decade. The geologic record provides us with abundant evidence for such perpetual natural climate variability, from icecaps reaching almost to the equator to none at all, even at the poles.

The climate debate is, in reality, about a 1.6 watts per square metre or 0.5 per cent discrepancy in the poorly known planetary energy balance." (Jan Veizer)

At a glance

Science, in all of its aspects, is an ongoing matter. It is based on making progress. For a familiar example, everyone knows that the dinosaurs died out suddenly, 65 million years ago. They vanished from the fossil record. The science is settled on that. But how and why that happened is still a really interesting research area. We know a monster asteroid smacked into the planet at roughly the same time. But we cannot yet conclude with 100% certainty that the asteroid bore sole responsibility for everything that followed.

With regard to climate science, the basis of the greenhouse effect was demonstrated in the 19th Century. The effect on global temperature through doubling the concentration of atmospheric CO2 had been calculated before 1900 and was not far off modern estimates. Raising global temperature causes Earth's climatic belts to shift polewards. Higher temperatures reduce the amount of land-ice on the planet. That in turn causes sea levels to rise. These are such simple basic physical principles that we can confidently state the science is settled on all of them.

Where the science is less settled is in the fine detail. For example, if you live in a coastal town at a low elevation, you would obviously like to know when it is likely to be affected by rising seas. But that's difficult.

Difficult because changes in sea levels, variations in the sizes of tides and weather patterns are all factors that operate independently of each other and on different time-scales. We may well know that a big storm-surge hitting the coast at high water on a spring tide is the worst-case scenario, but we don't know exactly when that might happen in the decades ahead. Too many variables.

Such minute but important details are where the science isn't settled. Yes we know that if we carry on spewing out tens of billions of tonnes of CO2 every year, things will get really bad. Where and when is the tricky bit. But if climate change was a deadly pathogen, for which there was a vaccine, most of us would get that jab.

In passing, the myth in the box above illustrates a key tactic of misinformation-practitioners, to mix up a whole bunch of talking-points into a rhetorical torrent. The classic example of the practice is the 'Gish-gallop'.

The term Gish-gallop was coined in reference to a leading American member of the creationist movement, Duane Gish (1921-2013). Gish was well-known for relishing fiery public debates with evolutionists. He perfected the method of presenting multiple arguments in a rapid-fire but scattergun manner so that they are impossible to answer in a structured form. It's the opposite of scientific discussion. The Gish-galloper appears to the viewers or listeners to be winning the debate. 'Appears' is the keyword here, though. If you can recognise a Gish-gallop developing, you can make your own mind up quickly.

Please use this form to provide feedback about this new "At a glance" section. Read a more technical version below or dig deeper via the tabs above!

Further details

Deniers often claim that the science of anthropogenic global warming (AGW) is not 'settled'. But think about this for a moment. No science is ever completely settled. Science deals in probabilities, not certainties. When the probability of something being correct approaches 100%, though, scientists agree that's the most likely answer. Consensus is achieved.

Thus we agree that certain pathogens can make us extremely unwell. We agree that a big asteroid hitting the planet would be nothing short of catastrophic. We agree that if we live in a district prone to tornadoes, it makes sense to have a good storm-shelter in your home. There are countless other examples, all of which can be filed under the same term, 'obvious'. That's even if we don't know exactly when the next pandemic, impact or tornado outbreak will occur.

Climate science deniers, on the other hand, insist that results must be double-checked, triple-checked and uncertainties must be narrowed before any action is taken. This is basically stalling for time, since the basic principles behind AGW have been staring us in the face for decades. It's also very misleading because by the time scientific results are offered up to policymakers, they already have been quintuple-checked.

Scientists have been predicting AGW with increasing confidence since the 1950s. Indeed, the hypothesis, backed up by detailed calculations, was first proposed in 1896. As science learned more and more about the climate system, a consensus gradually emerged. Many different lines of inquiry all converged into the IPCC’s 2007 conclusion that it is more than 90% certain that anthropogenic greenhouse gases are causing most of the observed global warming.

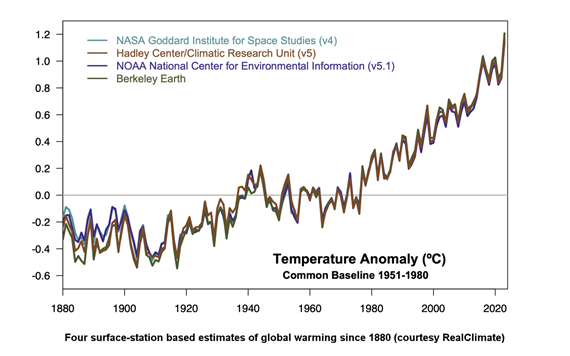

Some aspects of the science of AGW are known with near 100% certainty. The greenhouse effect itself is as established a phenomenon as any. There is no reasonable doubt that the global climate is warming (fig. 1). And there is also a clear trail of evidence leading to the conclusion that it’s caused by our greenhouse gas emissions. Some aspects are less certain; for example, the net effect of aerosol pollution is known to be negative, but the exact value needs to be better constrained. We're working on it. But it changes nothing regarding the basic principles.

Fig. 1: the latest temperature anomalies from four leading datasets, relative to a 1951-1980 baseline. The trend continues upwards and upwards. Graphic: Realclimate.

What about those remaining uncertainties? Should we wait for 100% certainty before taking action? No. Outside of logic and mathematics, we do not live in a world of absolute certainties. Science comes to its conclusions based on the balance of evidence. The more independent lines of evidence are found to support a scientific hypothesis, the closer it is likely to be to the truth. Hypotheses are tested to death before they are able to graduate into a theory. If someone tells you something is 'only a theory', they do not know what they are talking about. Theories are extremely robust explanations.

Just because some details about AGW are still not well understood, that should not cast into doubt our understanding of the big picture: humans are causing global warming. It is specifically down to our perturbation of Earth's carbon cycle by chucking some 44 billion tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere every year. That's around a hundred times more than annual volcanic emissions. It's such a huge amount it's almost incomprehensible.

In most aspects of our lives, we think it rational to make decisions based on incomplete information. We all take out insurance when there is even a slight probability that we will need it. We don't know when that tornado might pay a visit, but we want to be covered for the possibility that the house might get flattened, because we all know tornadoes can flatten houses.

Likewise, we don't know the exact details in terms of when or how disasters may strike due to global warming. Nevertheless, we know it will make more intense rainfall events more likely. We know it will cause more land-ice to melt, further raising sea levels. We know it will make fire-weather more common and intense. We know it will cause agriculture to be compromised, to the point of non-feasibility in some places. We know it will displace human populations. These are all very basic principles based on elementary physics. In other words, they are obvious. Why, then, do we ignore such settled things?

Last updated on 7 April 2024 by John Mason. View Archives

Arguments

Arguments

Climate Myth...