Is the science settled?

What the science says...

| Select a level... |

Basic

Basic

|

Intermediate

Intermediate

| |||

|

That human CO2 is causing global warming is known with high certainty & confirmed by observations. |

|||||

Climate Myth...

The science isn't settled

"Many people think the science of climate change is settled. It isn't. And the issue is not whether there has been an overall warming during the past century. There has, although it was not uniform and none was observed during the past decade. The geologic record provides us with abundant evidence for such perpetual natural climate variability, from icecaps reaching almost to the equator to none at all, even at the poles.

The climate debate is, in reality, about a 1.6 watts per square metre or 0.5 per cent discrepancy in the poorly known planetary energy balance." (Jan Veizer)

At a glance

Science, in all of its aspects, is an ongoing matter. It is based on making progress. For a familiar example, everyone knows that the dinosaurs died out suddenly, 65 million years ago. They vanished from the fossil record. The science is settled on that. But how and why that happened is still a really interesting research area. We know a monster asteroid smacked into the planet at roughly the same time. But we cannot yet conclude with 100% certainty that the asteroid bore sole responsibility for everything that followed.

With regard to climate science, the basis of the greenhouse effect was demonstrated in the 19th Century. The effect on global temperature through doubling the concentration of atmospheric CO2 had been calculated before 1900 and was not far off modern estimates. Raising global temperature causes Earth's climatic belts to shift polewards. Higher temperatures reduce the amount of land-ice on the planet. That in turn causes sea levels to rise. These are such simple basic physical principles that we can confidently state the science is settled on all of them.

Where the science is less settled is in the fine detail. For example, if you live in a coastal town at a low elevation, you would obviously like to know when it is likely to be affected by rising seas. But that's difficult.

Difficult because changes in sea levels, variations in the sizes of tides and weather patterns are all factors that operate independently of each other and on different time-scales. We may well know that a big storm-surge hitting the coast at high water on a spring tide is the worst-case scenario, but we don't know exactly when that might happen in the decades ahead. Too many variables.

Such minute but important details are where the science isn't settled. Yes we know that if we carry on spewing out tens of billions of tonnes of CO2 every year, things will get really bad. Where and when is the tricky bit. But if climate change was a deadly pathogen, for which there was a vaccine, most of us would get that jab.

In passing, the myth in the box above illustrates a key tactic of misinformation-practitioners, to mix up a whole bunch of talking-points into a rhetorical torrent. The classic example of the practice is the 'Gish-gallop'.

The term Gish-gallop was coined in reference to a leading American member of the creationist movement, Duane Gish (1921-2013). Gish was well-known for relishing fiery public debates with evolutionists. He perfected the method of presenting multiple arguments in a rapid-fire but scattergun manner so that they are impossible to answer in a structured form. It's the opposite of scientific discussion. The Gish-galloper appears to the viewers or listeners to be winning the debate. 'Appears' is the keyword here, though. If you can recognise a Gish-gallop developing, you can make your own mind up quickly.

Please use this form to provide feedback about this new "At a glance" section. Read a more technical version below or dig deeper via the tabs above!

Further details

Deniers often claim that the science of anthropogenic global warming (AGW) is not 'settled'. But think about this for a moment. No science is ever completely settled. Science deals in probabilities, not certainties. When the probability of something being correct approaches 100%, though, scientists agree that's the most likely answer. Consensus is achieved.

Thus we agree that certain pathogens can make us extremely unwell. We agree that a big asteroid hitting the planet would be nothing short of catastrophic. We agree that if we live in a district prone to tornadoes, it makes sense to have a good storm-shelter in your home. There are countless other examples, all of which can be filed under the same term, 'obvious'. That's even if we don't know exactly when the next pandemic, impact or tornado outbreak will occur.

Climate science deniers, on the other hand, insist that results must be double-checked, triple-checked and uncertainties must be narrowed before any action is taken. This is basically stalling for time, since the basic principles behind AGW have been staring us in the face for decades. It's also very misleading because by the time scientific results are offered up to policymakers, they already have been quintuple-checked.

Scientists have been predicting AGW with increasing confidence since the 1950s. Indeed, the hypothesis, backed up by detailed calculations, was first proposed in 1896. As science learned more and more about the climate system, a consensus gradually emerged. Many different lines of inquiry all converged into the IPCC’s 2007 conclusion that it is more than 90% certain that anthropogenic greenhouse gases are causing most of the observed global warming.

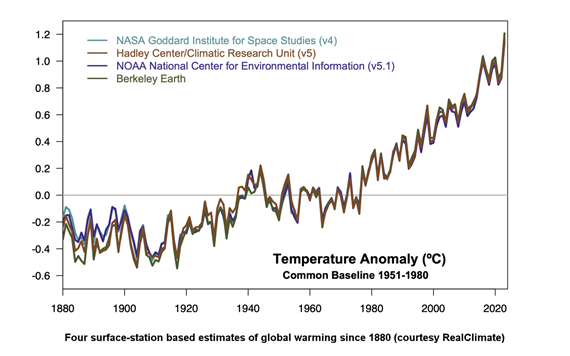

Some aspects of the science of AGW are known with near 100% certainty. The greenhouse effect itself is as established a phenomenon as any. There is no reasonable doubt that the global climate is warming (fig. 1). And there is also a clear trail of evidence leading to the conclusion that it’s caused by our greenhouse gas emissions. Some aspects are less certain; for example, the net effect of aerosol pollution is known to be negative, but the exact value needs to be better constrained. We're working on it. But it changes nothing regarding the basic principles.

Fig. 1: the latest temperature anomalies from four leading datasets, relative to a 1951-1980 baseline. The trend continues upwards and upwards. Graphic: Realclimate.

What about those remaining uncertainties? Should we wait for 100% certainty before taking action? No. Outside of logic and mathematics, we do not live in a world of absolute certainties. Science comes to its conclusions based on the balance of evidence. The more independent lines of evidence are found to support a scientific hypothesis, the closer it is likely to be to the truth. Hypotheses are tested to death before they are able to graduate into a theory. If someone tells you something is 'only a theory', they do not know what they are talking about. Theories are extremely robust explanations.

Just because some details about AGW are still not well understood, that should not cast into doubt our understanding of the big picture: humans are causing global warming. It is specifically down to our perturbation of Earth's carbon cycle by chucking some 44 billion tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere every year. That's around a hundred times more than annual volcanic emissions. It's such a huge amount it's almost incomprehensible.

In most aspects of our lives, we think it rational to make decisions based on incomplete information. We all take out insurance when there is even a slight probability that we will need it. We don't know when that tornado might pay a visit, but we want to be covered for the possibility that the house might get flattened, because we all know tornadoes can flatten houses.

Likewise, we don't know the exact details in terms of when or how disasters may strike due to global warming. Nevertheless, we know it will make more intense rainfall events more likely. We know it will cause more land-ice to melt, further raising sea levels. We know it will make fire-weather more common and intense. We know it will cause agriculture to be compromised, to the point of non-feasibility in some places. We know it will displace human populations. These are all very basic principles based on elementary physics. In other words, they are obvious. Why, then, do we ignore such settled things?

Last updated on 7 April 2024 by John Mason. View Archives

Arguments

Arguments

I take that this sentence

"anthropogenic greenhouse gases are causing most of the observed global warming"

is an essential part of AGW theory.

Can someone please offer a practical method of how to disprove it?

Unfortunately so far I failed to find one.

h-j-m @61, each of the following methods states a condition which has been experimentally tested and is known to be false, but which would falsify the theory if true.

Method 1: Warming of land surfaces equal warming of oceans, showing the change in temperature is caused by changes of SST rather than forcing.

Method 2: Stratosphere warming as troposphere warm showing the warming to be dominated by changes in solar radiance.

Method 3: Meso-sphere and thermosphere increasing in volume (showing that they are warming) as troposphere warms.

Method 4: Warming exists even though anthropogenic forcing factors remain constant.

Method 5: Known natural forcings are larger than known anthropogenic forcings.

Method 6: Width of anthropogenic GHG absorption spectra in outgoing LW radiation unchanged over time.

I am sure the list can be extended substantially, particularly once we start applying statistical tests rather than the crude method of simple falsification. It should be noted that if there were reasonable doubt about the theory, competing natural explanations would not have been falsified (they all have been).

Now, here is the real challenge. Find a theory that contradicts the claim that is both falsifiable and has not already been falsified. It is a challenge "skeptics" seem to avoid like the plague.

Further to 6 - measure the change in surface radiation or OLR and then find that is inconsistent with calculated change due to increased GHG.

You could also add - models based on AGW forcing would not reproduce past climate within the errors of model and forcing. You might think from arguments about paleo that this isnt a strong argument, but note that you can use this method to disprove alternative hypotheses like "the sun explains it all". "GHG changes have no effect".

I think that the easy practical ways to disprove AGW were all tried long ago and failed with explains your problem with find them.

Thinking on this further - that statement is not "an essential part of AGW theory". It is an outcome of the current theory of climate. Falsifying climate theory is same as for any other theory - the theory must change if predictions derived from the theory do not match observation with both the limits of prediction and limits on observation. One of the problems with claims to falsify climate theory is that they falsify predictions that climate theory does not make.

I have some questions related to this that have been bothering me for a while.

This article isn't about equilibrium climate sensitivity from double co2, but I'll use that for my point. the IPCC report gives a value of 2 to 4.5 C with a likely value of 3C and confidence level of greater than 66%. Less than 1.5C has a confidence level of less than 10%.

This is where I'm confused, for very well understood fields, such as heat transfer, equilibrium values can be calculated with a high degree of accuracy. For example, we can calculate the equilibrium temperature that a mixture of 1lb of 80F water and 1lb of 60F water would reach. Or in vibrations, how much a spring would stretch when it reaches rest from a hanging mass.

Obviously these are simple examples, but the point is that equilibrium values can be calculated with a high degree of accuracy in well understood fields certainly. The 5% not understood in climate looks like it has a pretty significant impact on the calculation of an equilibrium value. So why is the topic of climate considered well understood? Thanks

engineer,

I think that the problem is that you are trying to compare climate science with the hardest of hard sciences -- engineering sciences, like classical physics. Many other sciences are not nearly so precise, including quantum physics, biology, neuroscience, medicine and more difficult chemistry (especially the state of chemistry before the development of the electron microscope).

Would you consider all of these fields to be "not well understood?"

Understanding the feedback processes well does not necessarily mean that crucial numbers can be extracted easily. Things like - amount of aerosol, full thermal description of ocean, cloud vapour response etc. The Argo network, better satellite measurement, GRACE and so on eventually allow for more precision.

engineer:

I will answer the question with more questions.

1) you are selecting some very simple examples from heat transfer (mixing two different quantities, at two temperatures, of the same fluid) and the properties of materials (a single Hookian spring). They are high-school "engineering", not engineering school engineering. How simple is it to calculate the peak spark plug tip temperature in an F-1 racing engine at the end of a straight-away on the 72nd lap of the race at [pick a course] on a hot summer afternoon - from first principles? Would you consider the design of racing engines to be an area that is not well understood?

2) I would think that brige-building, slope stability calculations, etc. would be considered well understood engineering areas. Why does standard design practice often use relatively large (e.g. 2 or greater) factors of safety? Surely any factor of safety greater than one will do? (For those not familar with the term, a design factor of safety of 2 means that the design strength is twice the needed strength.)

3) a standard physics example of things that are difficult to calculate is the n-body problem. Does this difficulty in calcuating an exact answer mean that our understanding of gravity is not well understood?

4) If you wish to continue the discussion, would it be better if we did so without rhetorical questions?

so is the uncertainty mainly the result of the lack of theoretical understanding or the lack of more sophisticated technology (e.g. better satellites)? How much of the uncertainty in equilibrium climate sensitivity is from a lack of theoretical understanding?

@ bob, relax man. I'm not sure why you're so defensive.

Good question. As far as know, for ECS you need to know where feedbacks will stabilize. Ie if you perturb CO2, where does T settle when all feedbacks are in equilibrium. Now I think you could say there is a lot of confidence about what the feedbacks are, a lot of confidence about how the feedbacks work, but a lot less confidence about quantifying some of those processes accurately. (eg the complex dance of aerosol, water vapour, temperature and clouds).

thank you. that explained a lot.

scaddenp, last question. when you say "a lot less confidence quantifying some of those processes accurately" is that due to technology limitations (computing power) or theory? thanks

engineer:

...it is odd that you interpret my somewhat-rhetorical questions as "defensive", when you yourself began with somewhat-rhetorical questions. Granted, it can be difficult to read tone into a written comment, but you started off with what semed like a "gee, this should be so simple if it is well-understood" sort of comment. It reminded me of the following XKCD comic:

Perhaps a better start would have been to pose the question something like "What part are understood, and where does uncertainty in this value come from?" (as you are beginning to ask now) rather than implying it can't be "well understood" because it can't be predicted as easily or accurately as the simple examples you gave. The question relates to the How reliable are climate models? discussion, where you can find out much more about how the reliability is examined.

In a system as complex as global climate, you can have uncertainty in predictions due to uncertainty in the measurement of input variables, even if the physics of those portions of the system are well understood at a theoretical level. For example, consider the effect of aerosols. The radiative effect of a specific aerosol can be modelled quite well, given sufficient data about the size distribution, physical, and optical properties of the aerosol, etc., but getting detailed measurements of those physical properties over huge swaths of the atmosphere over sufficient time can be extremely difficult. Even if the technology exists (e.g AERONET), budgets aren't infinite and measured data is incomplete.

Then take that difficulty into the future, and try to predict exactly what the future aerosol state will be. It's not that it's hard to predict what a particular aerosol will do - it's hard to predict exactly what will be up there.

There can be quite a gap between a qualitiive description of a process (eg think ENSO) and a computer model able to capture it, but a big factor is limitations on the measurement system and time length of good data. (eg for Argo we have only 10 years so far). If you want quantitive models, you need accurate measurements. As far as I know, aerosol measurements are still short of modellers hopes.