How reliable are climate models?

What the science says...

| Select a level... |

Basic

Basic

|

Intermediate

Intermediate

| |||

|

Models successfully reproduce temperatures since 1900 globally, by land, in the air and the ocean. |

|||||

Climate Myth...

Models are unreliable

"[Models] are full of fudge factors that are fitted to the existing climate, so the models more or less agree with the observed data. But there is no reason to believe that the same fudge factors would give the right behaviour in a world with different chemistry, for example in a world with increased CO2 in the atmosphere." (Freeman Dyson)

At a glance

So, what are computer models? Computer modelling is the simulation and study of complex physical systems using mathematics and computer science. Models can be used to explore the effects of changes to any or all of the system components. Such techniques have a wide range of applications. For example, engineering makes a lot of use of computer models, from aircraft design to dam construction and everything in between. Many aspects of our modern lives depend, one way and another, on computer modelling. If you don't trust computer models but like flying, you might want to think about that.

Computer models can be as simple or as complicated as required. It depends on what part of a system you're looking at and its complexity. A simple model might consist of a few equations on a spreadsheet. Complex models, on the other hand, can run to millions of lines of code. Designing them involves intensive collaboration between multiple specialist scientists, mathematicians and top-end coders working as a team.

Modelling of the planet's climate system dates back to the late 1960s. Climate modelling involves incorporating all the equations that describe the interactions between all the components of our climate system. Climate modelling is especially maths-heavy, requiring phenomenal computer power to run vast numbers of equations at the same time.

Climate models are designed to estimate trends rather than events. For example, a fairly simple climate model can readily tell you it will be colder in winter. However, it can’t tell you what the temperature will be on a specific day – that’s weather forecasting. Weather forecast-models rarely extend to even a fortnight ahead. Big difference. Climate trends deal with things such as temperature or sea-level changes, over multiple decades. Trends are important because they eliminate or 'smooth out' single events that may be extreme but uncommon. In other words, trends tell you which way the system's heading.

All climate models must be tested to find out if they work before they are deployed. That can be done by using the past. We know what happened back then either because we made observations or since evidence is preserved in the geological record. If a model can correctly simulate trends from a starting point somewhere in the past through to the present day, it has passed that test. We can therefore expect it to simulate what might happen in the future. And that's exactly what has happened. From early on, climate models predicted future global warming. Multiple lines of hard physical evidence now confirm the prediction was correct.

Finally, all models, weather or climate, have uncertainties associated with them. This doesn't mean scientists don't know anything - far from it. If you work in science, uncertainty is an everyday word and is to be expected. Sources of uncertainty can be identified, isolated and worked upon. As a consequence, a model's performance improves. In this way, science is a self-correcting process over time. This is quite different from climate science denial, whose practitioners speak confidently and with certainty about something they do not work on day in and day out. They don't need to fully understand the topic, since spreading confusion and doubt is their task.

Climate models are not perfect. Nothing is. But they are phenomenally useful.

Please use this form to provide feedback about this new "At a glance" section. Read a more technical version below or dig deeper via the tabs above!

Further details

Climate models are mathematical representations of the interactions between the atmosphere, oceans, land surface, ice – and the sun. This is clearly a very complex task, so models are built to estimate trends rather than events. For example, a climate model can tell you it will be cold in winter, but it can’t tell you what the temperature will be on a specific day – that’s weather forecasting. Climate trends are weather, averaged out over time - usually 30 years. Trends are important because they eliminate - or "smooth out" - single events that may be extreme, but quite rare.

Climate models have to be tested to find out if they work. We can’t wait for 30 years to see if a model is any good or not; models are tested against the past, against what we know happened. If a model can correctly predict trends from a starting point somewhere in the past, we could expect it to predict with reasonable certainty what might happen in the future.

So all models are first tested in a process called Hindcasting. The models used to predict future global warming can accurately map past climate changes. If they get the past right, there is no reason to think their predictions would be wrong. Testing models against the existing instrumental record suggested CO2 must cause global warming, because the models could not simulate what had already happened unless the extra CO2 was added to the model. All other known forcings are adequate in explaining temperature variations prior to the rise in temperature over the last thirty years, while none of them are capable of explaining the rise in the past thirty years. CO2 does explain that rise, and explains it completely without any need for additional, as yet unknown forcings.

Where models have been running for sufficient time, they have also been shown to make accurate predictions. For example, the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo allowed modellers to test the accuracy of models by feeding in the data about the eruption. The models successfully predicted the climatic response after the eruption. Models also correctly predicted other effects subsequently confirmed by observation, including greater warming in the Arctic and over land, greater warming at night, and stratospheric cooling.

The climate models, far from being melodramatic, may be conservative in the predictions they produce. Sea level rise is a good example (fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Observed sea level rise since 1970 from tide gauge data (red) and satellite measurements (blue) compared to model projections for 1990-2010 from the IPCC Third Assessment Report (grey band). (Source: The Copenhagen Diagnosis, 2009)

Here, the models have understated the problem. In reality, observed sea level is tracking at the upper range of the model projections. There are other examples of models being too conservative, rather than alarmist as some portray them. All models have limits - uncertainties - for they are modelling complex systems. However, all models improve over time, and with increasing sources of real-world information such as satellites, the output of climate models can be constantly refined to increase their power and usefulness.

Climate models have already predicted many of the phenomena for which we now have empirical evidence. A 2019 study led by Zeke Hausfather (Hausfather et al. 2019) evaluated 17 global surface temperature projections from climate models in studies published between 1970 and 2007. The authors found "14 out of the 17 model projections indistinguishable from what actually occurred."

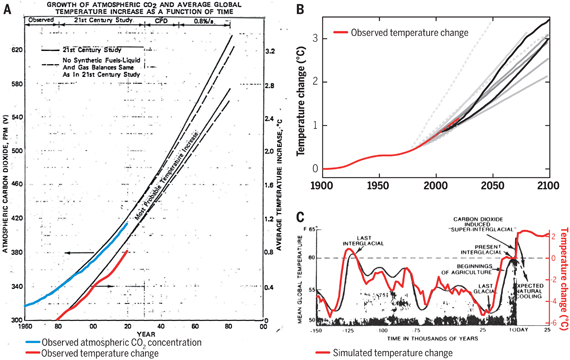

Talking of empirical evidence, you may be surprised to know that huge fossil fuels corporation Exxon's own scientists knew all about climate change, all along. A recent study of their own modelling (Supran et al. 2023 - open access) found it to be just as skillful as that developed within academia (fig. 2). We had a blog-post about this important study around the time of its publication. However, the way the corporate world's PR machine subsequently handled this information left a great deal to be desired, to put it mildly. The paper's damning final paragraph is worthy of part-quotation:

"Here, it has enabled us to conclude with precision that, decades ago, ExxonMobil understood as much about climate change as did academic and government scientists. Our analysis shows that, in private and academic circles since the late 1970s and early 1980s, ExxonMobil scientists:

(i) accurately projected and skillfully modelled global warming due to fossil fuel burning;

(ii) correctly dismissed the possibility of a coming ice age;

(iii) accurately predicted when human-caused global warming would first be detected;

(iv) reasonably estimated how much CO2 would lead to dangerous warming.

Yet, whereas academic and government scientists worked to communicate what they knew to the public, ExxonMobil worked to deny it."

Fig. 2: Historically observed temperature change (red) and atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration (blue) over time, compared against global warming projections reported by ExxonMobil scientists. (A) “Proprietary” 1982 Exxon-modeled projections. (B) Summary of projections in seven internal company memos and five peer-reviewed publications between 1977 and 2003 (gray lines). (C) A 1977 internally reported graph of the global warming “effect of CO2 on an interglacial scale.” (A) and (B) display averaged historical temperature observations, whereas the historical temperature record in (C) is a smoothed Earth system model simulation of the last 150,000 years. From Supran et al. 2023.

Updated 30th May 2024 to include Supran et al extract.

Various global temperature projections by mainstream climate scientists and models, and by climate contrarians, compared to observations by NASA GISS. Created by Dana Nuccitelli.

Last updated on 30 May 2024 by John Mason. View Archives

Arguments

Arguments

spunkinator99: Be sure to read the comments on that satellites post, especially the ones in 2015, and follow my comments' links to Tamino's blog that examines balloon radiosonde temperature measurements and their curiously increasing discrepancy from satellite measurements beginning around the year 2000. And read Glenn Tamblyn's comment on Spencer's blog.

spunkinator99: See also Bart Verheggen's post "John Christy, Richard McNider and Roy Spencer trying to overturn mainstream science by rewriting history and re-baselining graphs." And a new comment I just posted on the satellites SkS post.

Tom,

Thanks a ton! I'll take a look at your links. Should be helpful with my ultra-conservative friends!

Mike

Hawkins and Sutton are about to publish a peer-reviewed article explaining why and how choice of reference period is important when comparing model projections to observations. A pre-publication version is available now.

the best model is a will stay for a long time the linear interpolation of past observations :

physical sub-models with many parameters are useful to predict events which vary importantly and are testable,

but by defintion the global warming is not : it is a very small increase of temperature (of energy) resulting from very small increase of many parameters (the 1st one being CO2 concentration),

so forget the physics and study signal processing instead !

signal processing says that :

the more the model is complicated and not testable and the more the observations are random and not pure signal (signal to noise ratio), the the more the simpler model will be the best (linear interpolation)

the only way to overcome that problem is to get enough datas to model many sub-paramters which vary a lot and ARE testable :

such as a huge change in rainfall somewhere, a big and suddent change in somewhere in the ocean temperature or acidity, anything which vary a lot,

then find some physical explanations of that, test it and predict some non-trival facts (so prove your non-trivial physical explanation that was unknown or unproven before) and find some ways to extrapolate it to the global observations. do that many times with many researchers and after many time you'll be able to explain and predict and substract what was before considered as NOISE : once you explained that noise you'll get much cleaner observations and with a better signal/noise ratio and so on you'll be able to create better models.

this will take at least 20 years.

reuns - You open your comment with an incorrect statement: "the best model is a will stay for a long time the linear interpolation of past observations". This is completely wrong when looking at non-linear forcings applied to (in this case) climate. If the behavior is non-linear, a linear projection will be wrong.

'Signal processing', or more appropriately statistics, is fine for analyzing past behaviors of a system. But projecting ahead in a SP approach requires (gasp) actual physics, and looking at the input/output relationships involved.

The rest of your comment is essentially a claim that the climate is too complex to model and project, which I believe has been sufficiently addressed by the fact that observed temperatures and for that matter regional patterns are indeed reproduced within expected variation by GCMs.

It's physics all the way down - if modeling does a reasonable job of reproducing the physics, we don't need to test an infinite variety of cases. That's just a call for delay, which turns into a continually moving goalpost fallacy where there will never be enough information (in the opinion of the delayers) to make any kind of decisions...

Model predictions for a parameters with a huge amount of unpredictable internal variability like surface temperature do take time to validate. However, the models predict a great many other variables with far less internal variability (eg OHC, clear sky surface radiation etc) and can be tested on that. Have you read the IPCC chapter on model validation?

Can someone update this to show the 2015 data?

Can I help?

FrankShann - Yes, to 'predict' involves a result that wasn't input to the model, but given that GCMs don't have temperature observations as inputs, rather the forcings and the physics, even a retrodiction is still producing results that weren't inputs. Now as to 'tuning' models, what occurs in real life (as opposed to rhetoric) is that when models differ from observations at any scale, including regional variations, relative humidity, ocean currents, etc., the physics for that portion of the model are investigated for errors in the physics. Then the models with (hopefully more accurate) physics are run to see how well they reproduce observations. They are not tuned by temperatures, as erroneous physics re-tuned to a specific output will become even more erroneous, but rather to physical observations at all scales.

Purely statistical models do get tuned, but GCMs are physical models. And the many apparent attempts to dismiss models based upon efforts to faithfully reproduce physical observations, casting them instead as attempts to get a specific output temperature, are therefore incorrect.

The primary results of GCMs are projections, which is to say conditional predictions - if forcing change X occurs, the climate will evolve as Y over time. The CMIP5 model runs projected certain temperatures given specific forcing estimates, and those do diverge from observations - but then so do the observed forcings diverge from the forcing estimates. When we check those conditional predictions using actual forcings, to see what the models show in that case, we find that they are actually quite accurate, that the observations fall well within the bounds of model variability. And thus the results of the models are indeed "predictions". Conditional predictions of the relationships between forcings and climate evolutions.

KR @959. Thank you for taking the trouble to respond to my posts in www.skepticalscience.com/republicans-favorite-climate-chart-has-serious-problems.html and for explaining how GCMs are developed. However...

1. The word "predict" means to state what will happen in the *future* (Latin prae- "beforehand" + dicare "say"), or to state the existence of something that is *undiscovered* (such as Einstein's prediction of gravitational waves). My source is the Oxford English Dictionary. Any other meaning of predict is jargon and will be misinterpreted by most readers (especially if, as in Dana's post, it is not flagged as being used in an unconventional sense). For Skeptical Science to "explain what peer reviewed science has to say about global warming" to the general public, it has to use words in the sense understood by the general public (or clearly flag the use of jargon).

2. Dana presented a graph of CMIP5 modelling of global mean surface temperature (GMST) from 1880 to 2015. By definition, the CMIP5 estimates from 1880 to 2000 are not pre-diciton (before-stated), they are "hindcasting" (see point 4, below). Yet Dana implies that this graph is evidence that CMIP5 has "done an excellent job predicting how much temperatures at the Earth’s surface would warm" without any hint that he is using "predicting" to mean something other than "stating that a specified event will happen in the future" (OED).

Additional (peripheral) comments...

3. Even with a jargon definition of predict, experience in experimental science has shown that even randomised trials are subject to bias if they are not double blind. Development of the CMIP5 model was not blinded to GMST, so it is subject to bias. Consequently, the only rigorous validation of CMIP5 is how well it predicts future climate.

4. Look at the first sentence in the Intermediate section of this thread. "There are two major questions in climate modelling - can they accurately reproduce the past (hindcasting) and can they successfully predict the future?" In Skeptical Science's own words in this very thread, hindcasting is distinct from prediction.

FrankShann @960, you quote as your source the Oxford English Dictionary but my print version of the Shorter Oxford gives an additional meaning of predict as "to mention previously" ie, to have said it all before. That is equally justified as a meaning of 'predict' by its Latin roots which are never determinative of the meaning of words (although they may be explanatory of how they were coined). The actual meaning of words is given by how they are in fact used. On that basis, the mere fact that there is a "jargon" use of the word, means that 'predict' has a meaning distinct from 'forecast' in modern usage. Your point three refutes your first point.

For what it is worth, the online Oxford defines predict as to "Say or estimate that (a specified thing) will happen in the future or will be a consequence of something". That second clause allows that there can be predictions which do not temporally precede the outcomes. An example of the later use is that it could be said that "being in an open network instead of a closed one is the best predictor of career success". In similar manner, it could be said that forcings plus basic physics is the best predictor of climate trends. This is not a 'jargon usage'. The phrase 'best predictor of' turns up over 20 million hits on google, including in popular articles (as above). And by standard rules of English, if x is a good predictor of y, then x predicts y.

As it happens, CMIP5 models with accurate forcing data are a good predictor of GMST. Given that fact, and that the CMIP5 experiments involved running the models on historical forcings up to 2005, it is perfectly acceptable English to say that CMIP5 models predict GMST up to 2005 (and shortly after with less accuracy based on thermal inertia). On this usage, however, we must say they project future temperatures, however, as they do not predict that a particular forcing history will occur.

As a side note, if any term is a jargon term in this discussion, it is 'retrodict', which only has 15,000 hits on google.

As a further sidenote, you would do well to learn the difference between prescriptive and descriptive grammar. Parallel to that distinction is a difference between prescriptive and descriptive lexicographers. The curious thing is that only descriptive lexicographers are actually invited to compose dictionaries - while those dictionaries are then used by amateur prescriptive lexicographers to berate people about language of which they know little.

The only real issue with Dana's using 'prediction' is if it would cause readers to be confused as to whether the CMIP5 output on GMST was composed prior to the first date in the series or not. No such confusion is likely so the criticism of the term amounts to empty pedantry.

FrankShann - As Tom Curtis points out, conditional predictions are indeed part of the definition (a basic part of physics, as it happens), and that's exactly what climate models provide. Trying to focus on only a single one of the multiple definitions in common usage is pedantry.

As to validation, the fact is that GCMs can reproduce not just a single thread of historic GMSTs, but in fact regional temperatures, precipitation, and even to some extent clouds (although with less accuracy at finer and finer details, and clouds are quite challenging). Those details are not inputs, but rather predictions of outcomes conditional on the forcings. _That_ validates their physics - and justifies taking the projections seriously.

We certainly do not need to wait decades before acting on what these models tell us.

Tom, I am intending to be descriptive - of what people who are not climate scientists think about using a graph of temperatures between 1880 and 2015 as evidence that CMIP5 has "done an excellent job predicting how much temperatures at the Earth’s surface would warm". I told a convenience sample of my university colleagues that "CMIP5 is a climate model developed from 2008 onwards" and asked, "Does this graph provide evidence that CMIP5 has done an excellent job predicting temperature?" None thought that it did.

I repeat, if Skeptical Science aspires to explain climate science to the general public, it needs to use words in the way they are understood by the general public (or flag the specialist meaning).

FrankShann @963, I can agree with you that 'predict' is not an ideal word in the context. The problem is that 'described temperatures' would be even worse. 'Retrodict' would be better except that for part of the data todate, it is in fact predicted (whether we take that from 2005, ie, the date of the last historical input, or from 2012, ie, the date experiments for inclusion in the IPCC AR5 needed to be completed, and which therefore are the results actually presented).

Having said that, your convenience sample was asked the wrong question. To truly test whether Dana used the wrong word, you should have given them an example of his sentences of equivalent, and asked:

Based on this sentence and graph

1) Was GMST an independant or dependant variable in CMIP5 models;

2) Were CMIP5 models constructed around 1880 or around 2010; and

3) Did CMIP5 models successfully or unsuccessfully model GMST.

Based on Dana's sentences, if they lead to significant confusion about any of these three points, there was a problem with his use of the word. If not, then not.

I have no doubt that forecast is the archetypal definition of 'predict' just as "unmarried, marriagable male" is the archetypal meaning of 'bachelor' (or was in the 1950s, I suspect the gender specification has now been dropped, or is in the process of being dropped). The later, however, does not cause confusion when we talk of bachelor degrees, or knights bachelor, and did not cause confusion when we first started hearing about 'bachelor girls'. We humans are smart enough to modify the meaning of words from the archetypal value based on context and without confusion. (Computers, not so much.) As a result we use that capacity for flexibility of communication when no word has the exact semantic value we require. We do it all the time, and typically seamlessly.

And that is all that Dana has done.

His problem was that there is no ideal word in the context. But a non-archetypal, but quite common usage of 'predict' worked well. I am sure he would welcome a better word, but none has been suggested. In particular, your suggestion, 'description' will cause confusion as to whether or not GMST is a dependant or independant variable in the models.

KR @962. I am not suggesting that we wait decades. I agree that urgent action is needed now, and should have been taken years ago. I am quibbling about a very minor matter - what the average person thinks about a graph of temperature from 1880-2015 as evidence to support the assertion that CMIP5 predicts temperature. That is, I suggest that it is not a good idea to use "predict" with a specialist meaning on a site aimed at people who are not climate scientists (and without pointing out that predict is being used with a non-standard meaning).

I was suggesting only that Dana consider altering one word, and substitute describe for predict, so that the text would read, "Climate models have done an excellent job describing how much temperatures at the Earth’s surface would warm". This does not alter the thrust of Dana's post in any way.

John Christy's misleading graph purports to show that CMIP5 does not model past temperatures well, and so cannot be trusted to predict future temperatures. Dana's graph provides strong evidence that CMIP5 is an excellent model of past GMST, which suggests it is very likely to be good at predicting future GMST (especially as previous CMIP models have predicted future GMST well even though they were not as good as CMIP5 at describing past temperatures).

@964 Tom, we differ about the question - your questions are not what Dana wrote, and they would be completely unintelligible to the general public. Despite your theoretical speculations, people who are not climate scientists did not think that the graph provides evidence that CMIP5 has done an excellent job in predicting temperature; they took predict to mean forecast.

We also disagree about describe. Saying that the model predicts temperature does not imply that temperature is a predictor variable in the model, and saying that the model describes temperature does not imply that temperature is a descriptive variable in the model. You can't have it both ways, although I suspect you may well try.

*Again* If Skeptical Science aspires to explain climate science to the general public, it needs to use words in the way they are understood by the general public (or flag the specialist meaning). If those who run the site will not accept this, then we are all worse off because the site will be less effective and it is important that it succeed.

FrankShann @965,

First, you do not test for reading comprehension by asking questions that can be answered by simply parroting the text. Ergo, questions that do so do not test for confusion or lack of confusion introduced by the terms used. And, yes, the precise wording of my questions woud be confusing to the general public, but a I presumed I was conversing with an intelligent person, I did not undertake an appropriate rephrasing required if I were to conduct an actual survey.

Second, you now appear to be indicating that in your convenience survey you showed members of the general public Dana's article, and asked them whether, from the use of the word predict, they would conclude that CMIP5 models were developed prior to 1880? That is certainly not how you described it before. Rather, you took a survey of people with a highly specialist knowledge on a few academic topics, and tested for the archetypal meaning of 'predict' in their usage. The survey population was not representative of the general public - particularly so with their usage of statistical terms. The survey was not double blind. And the survey did not test for whether or not Dana's wording would in anyway cause confusion. As supporting evidence for your position, it was worthless. That you cannot recognize this shows your knowledge of linguistics to be as abysmal as my knowledge of medicine.

I have not ever said that temperature was a predictor variable in the models. Indeed, I have said the exact opposite. Nor would I describe anything as a 'descriptor variable' which is a term that has no meaning that I am aware of.

What I would say is that both CO2 emissions and GMST are equally desribed by climate models. One, however, is an independant variable. The other a dependant variable. Saying that CMIP5 models 'describe GMST' leaves us completely in the dark as to whether GMST is dependant or independant.

Tom Curtis @966.

*If Skeptical Science aspires to explain climate science to the general public, it needs to use words in a way that is understood by the general public (or flag the specialist meaning).*

You seem very confident of your expertise on many subjects outside climate science. What precisely is your expertise on survey techniques? The survey questions suggested by you were of very low quality indeed. I didn't pretend that my survey was definitive, but your statement that the information is "worthless" is incorrect (it is often risky to assert absolutes in science). In fact, you have very little information about how I did the survey. I asked university staff because it was convenient (as I said), and because an educated sample was more likely to know that "predict" has alternative meanings (so was more likely to refute my hypothesis). You say, "I have no doubt [another absolute] that forecast is the archetypal definition of 'predict'" - which is consistent with the meagre evidence from my survey (where respondents took "predict" to mean "forecast").

You asserted (without presenting any evidence) that "your suggestion, 'description' will [another absolute] cause confusion as to whether or not GMST is a dependent or independent variable in the models". Who says? My point (which you overlook) is that "predict" is just as likely as "describe" to cause confusion as to whether GMST is a dependent or independent variable - both terms can be used to describe independent variables and your ignorance of the term "descriptor variables" is merely evidence of ignorance (and suggests that "describe" may be less likely than "predict" to be mistaken for an independent variable).

I did not intend to make such a big deal of it, but I still think that saying "Climate models have done an excellent job describing how much temperatures at the Earth’s surface have warmed" when combined with the 1880-2015 CMIP5 graph is less likely to cause confusion than Dana's wording. It still refutes Christy's misleading graph, which is far more important than my minor quibble about semantics.

As we seem to agree that climate change is an important problem that needs to be addressed urgently, is it time to call a truce over "predict" versus "describe" so we can spend more time fighting the deniers rather than squabbling with each other?

FrankShann - I agree that the question you pose (regarding "evidence to support the assertion that CMIP5 predicts temperature") will lead people to answer 'no', but that is because as stated it's an incomplete question.

The proper question is "Is there evidence to support the assertion that CMIP5 models predict temperatures from forcings?" The answer to that is certainly 'yes', as validated by their ability to reproduce past temperature evolutions on both the global and regional levels. And that indicates that their projections, conditional predictions, about the future are useful.

If you pose a poorly worded or incomplete question, you shouldn't be surprised by a nonsensical answer.

Splitting hair about semantics while the planet is accumulating heat at a rate that was only seen before during cataclysmic mass extinctions. Perhaps that's what is truly wrong about this species of ours...

From the handy-dandy SkS Glossary...

Climate model

spectrum or hierarchy

A numerical representation of the climate system based on the physical, chemical and biological properties of its components, their interactions and feedback processes, and accounting for all or some of its known properties. The climate system can be represented by models of varying complexity, that is, for any one component or combination of components a spectrum or hierarchy of models can be identified, differing in such aspects as the number of spatial dimensions, the extent to which physical, chemical or biological processes are explicitly represented, or the level at which empirical parametrizations are involved. Coupled Atmosphere-Ocean General Circulation Models (AOGCMs) provide a representation of the climate system that is near the most comprehensive end of the spectrum currently available. There is an evolution towards more complex models with interactive chemistry and biology (see Chapter 8). Climate models are applied as a research tool to study and simulate the climate, and for operational purposes, including monthly, seasonal and interannual climate predictions.

Definition courtesy of IPCC AR4.

All IPCC definitions taken from Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Working Group I Contribution to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Annex I, Glossary, pp. 941-954. Cambridge University Pres

KR @968. My question accurately represented Dana's post. He said "climate models have done an excellent job predicting how much temperatures at the Earth’s surface would warm", and immediately below that showed the graph of CMIP5 and temperature for 1880-2010. Dana did not say "from forcings", so neither did I. The title of the graph includes "using CMIP5 all-forcing experiments" and that was shown - but every person I asked said that the graph did not provide evidence that CMIP5 has done an excellent job predicting temperature - because the vast majority of people use predict to mean forecast. Even Tom Curtis agrees that there is "no doubt that forecast is the archetypal definition of 'predict'".

*If Skeptical Science aspires to explain climate science to the general public, it needs to use words in a way that is understood by the general public (or flag the specialist meaning).*

KR@968: Thanks, your statement

"The proper question is "Is there evidence to support the assertion that CMIP5 models predict temperatures from forcings?" The answer to that is certainly 'yes', as validated by their ability to reproduce past temperature evolutions on both the global and regional levels."

helps clear it up for this layman.

I do side with FrankShann, though, as it has not been clear to me to what extent past temperatures are inputs to the models. (After all, before Copernicus, anyone could predict a daily sunrise, knowing no physics at all.) It must be made clear that the models do not use past temperatures to predict the future temperatures. (like, Gee, I see a sine wave and a slope, so that should continue in the future.)

A passage like "We wrote the models during 2005 to 2010,(or whatever) and used the conditions and temperature of 1880 and the known forcings from then, like sunlight, CO2, and volcanoes, and then ran the models and successfuly predicted (or descibed) the temperatures from 1880 to 2010." would be more clear to me.

A doubter would still wonder, since we knew in advance the temperatures to describe, to what extent we tweaked parameters to get the right temperatures. So you would have to show him how the tweak was for proper humidity, wind, or what ever, not just to get the desired temperature.

Good points. If you want to look at how past model "predictions" of the future have gone, then you could of course look at how, say, one of the earliest models, Manabe and Weatherall 1975, used by Wally Broecker, is doing now. See here. It would be nice to update this chart. There are other predictions (eg FAR) also in the "Lessons from past climate predictions" series that are worth looking at. Of course any serious evaluation has to compare actual forcings against what the prediction assumed if you want to assess skill at climate modelling rather than guessing emission rates. Broecker overestimated emissions but also looks to have underestimated sensitivity.

A very tentative suggestion...

In addition to @972 and @973: to convince most people, climate models need to be able to forecast *future* temperatures, and not just accurately describe *past* temperatures (I am avoiding the word "predict").

Unfortunately, you then need to forecast all the forcings for a given future year, as well as have a good climate model. Errors in your forecasts of the forcings may be at least as great as the errors in your climate model.

What about taking the current Best Available Model (BAM-2016) and saying "we forecast that global mean surface temperature (GMST) will be Z if the CO2 is V, El Nino is W, aerosols are X, volcanic activity is Y etc (with reliable sources for the values of the forcings defined in advance, such as the appropriate values from www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/global.html#global_data for CO2)? The model would be published in advance and the results updated each year. New models could be introduced over time (such as BAM-2020 in 2020) while still calculating the forecasts from previous models (such as BAM-2016).

Perhaps this has already been done, or models such as CMIP5 cannot be applied in this way, or some important forcings cannot be pre-specified in a suitable fashion, or there are other problems. As I say, this is merely a tentative suggestion.

FrankShann - That's the entire reason for the various Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) evaluated in the models, to bracket potential emissions. Shorter term variations (which include emergent ENSO type events), volcanic activity, solar cycle, etc, are also incorporated, but as those aren't predictable they are estimates.

Which doesn't matter WRT the 30 year projections from the models, as the natural variability is less than the effects of thirty year climate change trends, and the GCMs aren't intended for year to year accuracy anyway - rather, they are intended to probe long term changes in weather statistics, in the climate.