What is the link between hurricanes and global warming?

What the science says...

| Select a level... |

Basic

Basic

|

Intermediate

Intermediate

| |||

|

There is increasing evidence that hurricanes are getting stronger due to global warming. |

|||||

Climate Myth...

Hurricanes aren't linked to global warming

“According to the National Hurricane Center, storms are no more intense or frequent worldwide than they have been since 1850. […] Constant 24-7 media coverage of every significant storm worldwide just makes it seem that way.” (Paul Bedard)

At a glance

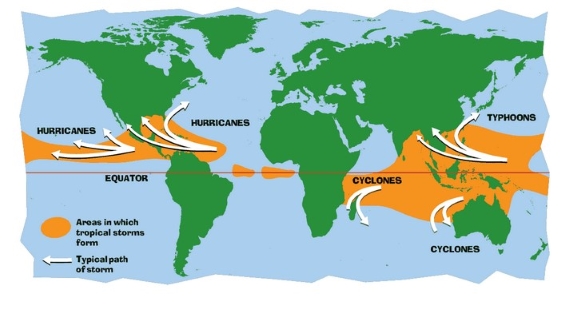

Hurricanes, Cyclones or Typhoons. These are traditional terms for near-identical weather-systems. The furious storms that affect the tropics have a fearsome reputation for the havoc they bring. Such storms are driven by the heat of the tropical oceans, where sea surface temperatures vary by just a few degrees Celsius and are almost always in the high twenties. Hurricane formation can only take place at such temperatures.

In the Atlantic, for example, a tropical storm-system begins life as a developing wave of low pressure tracking westwards out of Africa. Offshore in the tropical Atlantic, the warmth of the ocean's surface drives intense evaporation. That warmth and moisture provide the fuel for thunderstorm development.

Most such waves simply carry clusters of disorganised showers and thunderstorms. But in some, the storms organise into rain-bands. Once that happens, low-level warm and moist air floods in towards the low pressure centre from all compass points. But it does so in an inward spiralling motion. Why? That's due to the Coriolis Effect. Because the Earth rotates, circulating air is deflected to the right in the Northern Hemisphere, resulting in a curved path. In the Southern Hemisphere the air is deflected to the left. The effect is named after the French mathematician Gaspard Gustave de Coriolis (1792-1843), who studied energy transfer in rotating mechanical systems, such as waterwheels.

The other essential ingredient required to form and keep a hurricane going is low wind shear. Wind shear is defined as winds blowing at different speeds and in different directions at different heights in the Troposphere - the lower part of our atmosphere where weather occurs. For a hurricane, wind-shear of less than 10 knots from the surface to the high troposphere is perfect.

With those ingredients in place, an organised cluster of thunderstorms may spin up into a tropical depression. If conditions favour further development, a tropical storm will form and then strengthen into a hurricane. A hurricane has a minimum constant wind speed of 119 kilometres per hour (74 mph). The most intense Category 5 storms have sustained winds of more than 252 kilometres per hour (157 mph). Highest winds are typically concentrated around the inner rainbands that surround the hurricane's eye.

So, given the above, what will a warmer world result in?

It's a bit of a mixture due to the number of variables involved. The number of storms reaching Category 3-5 intensity is considered to have increased over recent decades. That's because warmer sea surface temperatures give a storm more fuel. Hurricane Beryl of June-July 2024 is a good example. It intensified from a mere tropical depression to a major hurricane in less than 48 hours and was the first recorded storm to reach Category 4 in the month of June. It was also the earliest Category 5 by some 15 days. In contrast, the number of individual systems in a given year appears to have decreased although the jury's still out on that. But one thing is a lot more certain. Extreme rainfalls.

There's a simple, memorable formula that describes how warmer air can carry more moisture: 7% more moisture per degree Celsius of temperature increase. Hurricanes already dump vast amounts of rain: in a warmer world that amount will only increase. Allowing further warming to take place simply makes an already bad situation worse.

Please use this form to provide feedback about this new "At a glance" section. Read a more technical version below or dig deeper via the tabs above!

Further details

The current research into the effects of climate change on tropical storms demonstrates the virtues and transparency of the scientific method at work. It also rebuts the oft-aired conspiracy-theory that scientists fit their findings to a predetermined agenda in support of climate change. They must be exceptionally good at it if that's the case. Normally a single Presidential term does not pass without various people leaking various things that would preferably be kept quiet. In the case of climate change, for this conspiracy theory to be even half-correct, they would have needed to keep it going without fail for two whole centuries! File under 'impossible expectations'.

In the case of storm frequency, there is no consensus and reputable scientists have two diametrically opposed hypotheses about increasing or decreasing frequencies of such events. The IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) therefore ascribes 'medium confidence' on the frequency of tropical systems remaining the same or decreasing a little. That basically means "we don't entirely know at the moment".

The background to these inquiries stems from a simple observation: extra heat in the air or the oceans is extra energy, and storms are driven by such fuel. What we do not know is whether we might see more storms as a result of extra energy or, as other researchers conclude, the storms may grow more intense. There is a growing body of evidence that since the mid-1970s, storms have been increasing in strength, and therefore severity. Looking forward, in a world that continues to warm, even more energy means storms will be more destructive, last longer and make landfall more frequently than in the past. AR6 gives increasing intensity a 'likely'. Because this phenomenon is strongly associated with sea surface temperatures (fig. 1), it is reasonable to expect that the increase in storm intensity and climate change are linked.

Fig. 1:the warm (and warming) tropical seas are the spawning-ground for hurricanes. Graphic: NASA.

Winds are just one impact of a hurricane: the other is flooding, from two key sources: firstly, storm surges and secondly, extreme rainfalls.

Like any deep area of low pressure, hurricanes have a sizable bulge of sea beneath their eye, accompanying them as they track along. This bulge - the storm surge - forms due to the phenomenally low pressure at the centre of such a storm, that may even fall below 900 millibars in some cases.

Damage caused by a storm surge is dependent on its size, forward speed, sea bed topography, coastal land altitude, whether it strikes at low or high tide and the size of the tide, controlled by the tidal cycle. Spring tides are the biggest and don't just happen in the spring: they occur twice a month. A worst-case scenario occurs where the following factors combine:

- the sea-bed abruptly changes landward from deep to shallow

- the coastal land is low-lying and populous

- the surge hits at high water on a spring tide

- the storm's central pressure is exceptionally low i.e. a Category 5 system

- the storm's forward motion is rapid

If that combination occurs, the damage can be tsunami-like in its effects. A trend towards more intense storms making landfall in a warmer world is therefore a matter of major concern. Add rising sea levels into the mix and one can clearly see the future potential for big trouble due to such surges.

Rainfall is the second source of misery and destruction in tropical systems and in most cases is the leading one. It's worth quoting directly from AR6 with regard to intense rainfalls:

"The average and maximum rain rates associated with tropical cyclones (TCs), extratropical cyclones and atmospheric rivers across the globe, and severe convective storms in some regions, increase in a warming world (high confidence)."

A simple formula (the Clausius-Clapeyron relation) expresses how warmer air is able to transport more moisture. The increased capacity is 7% more per degree Celsius of air temperature increase - something that's been understood since the 1850s. Provided a tropical system has access to increased heat and moisture as it tracks over Earth's ocean surface, it's guaranteed to drop more rainfall in a warmer world. The same principle explains why such systems start to disperse after landfall: that heat and moisture supply gets cut off and they lose their energy-source.

Note that the IPCC makes specific reference to rainfall rates. This is very important. If an inch of rain falls over 24 hours you might see rivers slowly going into spate. But if that same amount falls in just half an hour, you see news headlines regarding properties affected by flash-flooding.

So to conclude, there are things that are almost certain with regard to hurricane frequency, severity and impacts, but there are other things about which we don’t know for sure yet. What can we conclude? About hurricane frequency – not much; the jury is still out. About severity, they do seem to be packing stronger winds. About impacts, stronger winds, faster intensification and a trend of increasingly-severe flooding all seem likely.

With regard to the contested hypotheses about absolute frequency of tropical storms and climate change, we can say that these differing hypotheses are the very stuff of good science, and in this microcosm of climatology, the science is clearly not yet settled. It is also obvious that researchers are not shying away from refuting associations with climate change where none can be found. We can safely assume they don’t think their funding or salaries are jeopardised by publishing research into a serious problem that does not in some way implicate climate change!

Last updated on 3 July 2024 by John Mason. View Archives

Arguments

Arguments

Based on data from Maue, RN (2011): Global Frequency . I have studied the development of the number of tropical cyclones during the years January 1970 through September 2012 divided into the Northern and Southern Hemisphere. I would like to thank R.N. Maue for collecting data on tropical cyclones and making data public.

The reason why I have made this analysis is that there have been mistrust in the climate skeptical world to the predictions made by IPCC, and using the data from R.N. Maue it should be possible retrospectively to verify or falsify the prediction made using elementary statistical tools. In addition to this, I was not aware of the differences found below between the Northern and Southern Hemisphere.

The following graph shows the development of the number of tropical cyclones for the years January 1970 through September 2012.

Please use zoom to see details.

The number of Major Hurricanes is significantly growing in the Northern Hemisphere and the Southern Hemisphere, while the Tropical Storms are significantly decreasing in the Southern Hemisphere.

This is in line with IPCC’s prediction of increasing number of Major Hurricanes and a decreasing number of Tropical Storms.

Since hot sea water is the fuel for tropical cyclones, I understand why we will see an increasing number of Major Hurricanes. But I do not understand why the number of Tropical Storm is expected to decrease in the future as they already have done.

There is a positive correlation between then number of Tropical Storm, Hurricane and Major Hurricane within the Northern Hemisphere and the Southern Hemisphere respectively.

If you look at a shorter time span than 43 years, other observations could be made. For the years 2009-2012 the number of tropical cyclones is smaller than expected. However, 4 years are a too few years to put forwards a statement on a general trend. Please be aware that 2012 only includes 9 month so far.

There is an apparent difference in the development of the number of tropical cyclones in the Northern and Southern Hemisphere. There is more tropical cyclone in the Northern Hemisphere, approx. 68% out of the total number of tropical cyclones.

The following picture shows some of the differences between the Northern and Southern Hemisphere in respect of tropical cyclones:

The tropical cyclone prone area is much large in Northern Hemisphere than in the Southern Hemisphere.

When you look at number of Major Hurricanes per month, it appears that there is a remarkable difference in their distribution per month. In the following graph, I have shifted the month to produce frequency distribution by season.

The number of Major Hurricanes for the Northern Hemisphere shows a left skew distribution with a gradually decreasing trend after the peak at the month of September, while the number of Major Hurricanes for the Southern Hemisphere shows a more abrupt decreasing trend after the peak at the month of March.

The tropical cyclone season is 12 months for the Northern Hemisphere and 9 months for the Southern Hemisphere.

There is a 6 and 12 month cyclic variation in the number of tropical cyclones. This follows from the seasonal shift between the Northern and Southern Hemisphere and from a spectral analysis not shown here. The following graph shows the number of Tropical Storms worldwide for the years 2000-2012 by month:

I have used a generalized linear model with a linear trend and two harmonic terms with a cycle and 6 and 12 month to respectively in order to produce the graph above.

Please use zoom to see details.

The variation originates from merging the figures from the Northern and Southern Hemisphere, each with its own cyclic variations. The model explains 65% of the total variation. There is no significant trend and approx. 87 Tropical Storms are expected annually.

In total the number of tropical cyclones in the Southern Hemisphere makes up 32% of the total number of tropical cyclones.

The tropical cyclones prone area in the Southern Hemisphere makes up 42% of the total tropical cyclones prone area. This number is found by counting 5 * 5 degree squares on the map page 505 Marine Safety Information Chapter 35 Tropical Cyclones where tropical cyclones occur. As a first guess, this is probably OK to do so, but a better estimate is wanted.

The number of tropical cyclones in the Southern Hemisphere, calculated in proportion to tropical cyclone prone area, equals 0.42*6690= 2803. The actual number is 2134. This is significantly lower.

This leads to the following questions? 1) Why is the tropical cyclones prone area smaller in the Southern Hemisphere than in the Northern Hemisphere?

2) Why is the number of tropical cyclones in the Southern Hemisphere in proportion to area smaller than the in the Northern Hemisphere?

3) Are these findings in line with IPCC’s predictions?

Atlantic cyclones - biased information As a result of the dominance of US based news media worldwide, the information about the tropical cyclones in the Atlantic region is more dominant than from the other parts of the world. This can lead to an incorrect understanding of trends and causes, since the number of tropical cyclones in the Atlantic region accounts for only 12.6% of the total number of tropical cyclones. The Atlantic Tropical Storms, Hurricanes and Major Hurricanes accounts only for 13.1 %, 12.7 % and 10.8 % of the total number of Tropical Storms, Hurricanes and Major Hurricanes respectively.

More details can be found in the statistical analysis of tropical cyclone data from R.N.Maue Worldwide Hurricane analysis.

Seems like this thread is in need of some updating.

Here's the most recent news :

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Recent intense hurricane response to global climate change

Greg Holland, Cindy L. Bruyère | March 2013,

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00382-013-1713-0

Full article: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00382-013-1713-0/fulltext.html

Klaus @ 65, I think yet the answer to your questions 1 and 2 is to be found in the Sea Surface Temperature. This map of SST shows that the hurricanes appear, as expected, in the warmest areas :

[DB] Reduced image width to 450. Click on image for larger version.

A new denialist argument that I'm seeing more and more is that because the USA experienced fewer hurricanes in 2013 than in some previous years, global warming has stopped or is disproven!

That is such a collossal disconnect in logic that words fail me...

My analysis of the number of tropical storms only covers the period 1970-2012. This is the weak point, as far as I do not have data going back further. Therefore, I do not know if the development is caused by natural variations or if it is a result of the global warming. However the development is in line with the expectation from the global warming.

The graph of North Atlantic cyclone numbers in the post could do with updating. The 10-year average has concinued to rise and now sits above 16 per year.

N Atlantic hurricane numbers & major hurricane (catagory 3+) numbers have also risen but less dramatically and have presently their own little "hiatus." Add the argument about unreliable data prior to the 1970s, and it is difficult to establish with any certainty an AGW signal above the 'natural cycles'. The same goes for N Atlantic Accumulated Cyclone Energy (see here - usually 2 clicks to 'download your attachment').

Globally, beyond the N Atlantic, the data is even less reliable prior to 1970 (as Klaus Flemløse @70 would likely agree). So that Atlantic tropical cyclone graph is a bit of a rare beast.

This is in response to the unfolding disasters in the Carribean and Florida and the fact that this thread is a little out of date.

Recent relevant update from NOAA:

https://www.gfdl.noaa.gov/global-warming-and-hurricanes/

It seems that fresh data and recent analysis haven't changed things much.

On further reflection, it appears that NOAA is suggesting that frequency is essentially constant and intensity is (may be?) increasing over time.

The article linked to by SingletonEngineer has been repeatedly cited and linked to by more than one mainstream climate scientist who has been interviewed by the media about the climate change-hurricane* connection in recent articles about Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, Jose, and Katia.

Global Warming and Hurricanes: An Overview of Current Research Results posted on the website of NOAA’s Geophysical Fluids Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL). It was last revised on Aug 30, 2017.

*North Atlantic basin only.

Over the past couple of weeks, I have posted links to the following articles about the climate change-hurricane connection on the SkS Facebook page.

Did Climate Change Intensify Hurricane Harvey? by Robinson Meyer, The Atlantic, Aug 27, 2017

Climate change did not “cause” Harvey, but it’s a huge part of the story by David Roberts, Energy & Environment, Vox, Aug 28, 2017

Could Hurricane Harvey Deal A Fatal Blow To Climate Change Skepticism? by Jared Keller, Pacific Standard, Aug 28, 2017

Harvey Shows How Planetary Winds Are Shifting by Eric Roston, Bloomberg News, Aug 30, 2017

Does Harvey Represent a New Normal for Hurricanes? by Robinson Meyer, The Atlantic, Aug 29, 2017

Katrina. Sandy. Harvey. The debate over climate and hurricanes is getting louder and louder by Chris Mooney, Energy & Environment, Washington Post, Aug 30, 2917

What Hurricane Harvey says about risk, climate and resilience by Andrew Dressler, Daniel Cohan & Katharine Hayhoe. The Conversation US, Sep 1, 2017

Three things we just learned about climate change and big storms: Can the lessons of Harvey save us? by Paul Rosenberg, Salon, Sep 4, 2017

Denying Hurricane Harvey’s climate links only worsens future suffering by Dana Nuccitelli, Climate Consensus - the 97%, Guardian, Sep 5, 2017

Harvey and climate change: why it won't change minds by Amy Harder, Axios, Sep 5, 2017

Hurricane Harvey's aftermath could see pioneering climate lawsuits, Analysis by Sebastien Malo, Thomson Reuters Foundation, Sep 5, 2017

On Climate, Hurricanes, And Growth by Joseph Majkut, Niskanen Center, Aug 31, 2017

First Harvey, now Irma. Why are so many hurricanes hitting the U.S.? by Nisikan Akpan, PBS News Hour, Sep 6, 2017

The science behind the U.S.’s strange hurricane ‘drought’ — and its sudden end by Chris Mooney, Energy & Environment, Washington Post, Sep 7, 2017

Hurricane Irma is one of the most powerful Atlantic hurricanes ever: what we know by Brian Resnick, Science & Health, Vox, Sep 7, 2017

6 Questions About Hurricane Irma, Harvey and Climate Change by Sabrina Shankman, InsideClimate News, Sep 6, 2017

President Trump, hurricanes Harvey and Irma are sending you a message, Opinion by Andrés Oppenheimer, Miami Herald, Sep 7, 2017

What We Know about the Climate Change–Hurricane Connection by Michael E. Mann, Thomas C. Peterson & Susan Joy Hassol, Scientific American, Sep 8, 2017

As Hurricanes Irma and Harvey Slam the U.S., Climate Deniers Remain Steadfast by Marianne Lavelle, InsideClimate News, Sep 8, 2017

Ask the Experts: How Did 2 Such Powerful Hurricanes Occur Back to Back? by Annie Sneed, Scientific American, Sep 7, 2017

Another Way Climate Change Might Make Hurricanes Worse by Faye Flam, Bloomberg News, Sep 8, 2017

Will Irma Finally Change the Way We Talk About Climate? by David Wallace-Wells, Daily Intelligencer, New York Magazine, Sep 9, 2017

Irma and Harvey lay the costs of climate change denial at Trump’s door by Bob Ward, The Observer/Guardian, Sep 9, 2017

Hurricane Irma Linked to Climate Change? For Some, a Very ‘Insensitive’ Question. by Lisa Friedman, Climate, New York Times, Sep 11, 2017