What is the link between hurricanes and global warming?

What the science says...

| Select a level... |

Basic

Basic

|

Intermediate

Intermediate

| |||

|

There is increasing evidence that hurricanes are getting stronger due to global warming. |

|||||

Climate Myth...

Hurricanes aren't linked to global warming

“According to the National Hurricane Center, storms are no more intense or frequent worldwide than they have been since 1850. […] Constant 24-7 media coverage of every significant storm worldwide just makes it seem that way.” (Paul Bedard)

At a glance

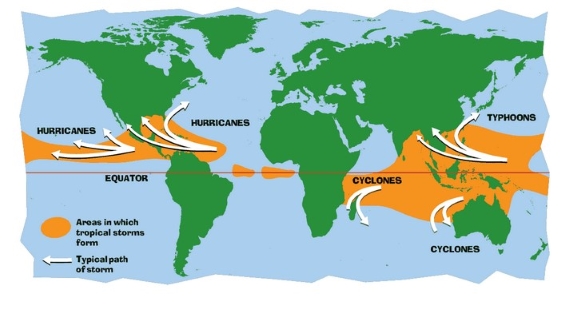

Hurricanes, Cyclones or Typhoons. These are traditional terms for near-identical weather-systems. The furious storms that affect the tropics have a fearsome reputation for the havoc they bring. Such storms are driven by the heat of the tropical oceans, where sea surface temperatures vary by just a few degrees Celsius and are almost always in the high twenties. Hurricane formation can only take place at such temperatures.

In the Atlantic, for example, a tropical storm-system begins life as a developing wave of low pressure tracking westwards out of Africa. Offshore in the tropical Atlantic, the warmth of the ocean's surface drives intense evaporation. That warmth and moisture provide the fuel for thunderstorm development.

Most such waves simply carry clusters of disorganised showers and thunderstorms. But in some, the storms organise into rain-bands. Once that happens, low-level warm and moist air floods in towards the low pressure centre from all compass points. But it does so in an inward spiralling motion. Why? That's due to the Coriolis Effect. Because the Earth rotates, circulating air is deflected to the right in the Northern Hemisphere, resulting in a curved path. In the Southern Hemisphere the air is deflected to the left. The effect is named after the French mathematician Gaspard Gustave de Coriolis (1792-1843), who studied energy transfer in rotating mechanical systems, such as waterwheels.

The other essential ingredient required to form and keep a hurricane going is low wind shear. Wind shear is defined as winds blowing at different speeds and in different directions at different heights in the Troposphere - the lower part of our atmosphere where weather occurs. For a hurricane, wind-shear of less than 10 knots from the surface to the high troposphere is perfect.

With those ingredients in place, an organised cluster of thunderstorms may spin up into a tropical depression. If conditions favour further development, a tropical storm will form and then strengthen into a hurricane. A hurricane has a minimum constant wind speed of 119 kilometres per hour (74 mph). The most intense Category 5 storms have sustained winds of more than 252 kilometres per hour (157 mph). Highest winds are typically concentrated around the inner rainbands that surround the hurricane's eye.

So, given the above, what will a warmer world result in?

It's a bit of a mixture due to the number of variables involved. The number of storms reaching Category 3-5 intensity is considered to have increased over recent decades. That's because warmer sea surface temperatures give a storm more fuel. Hurricane Beryl of June-July 2024 is a good example. It intensified from a mere tropical depression to a major hurricane in less than 48 hours and was the first recorded storm to reach Category 4 in the month of June. It was also the earliest Category 5 by some 15 days. In contrast, the number of individual systems in a given year appears to have decreased although the jury's still out on that. But one thing is a lot more certain. Extreme rainfalls.

There's a simple, memorable formula that describes how warmer air can carry more moisture: 7% more moisture per degree Celsius of temperature increase. Hurricanes already dump vast amounts of rain: in a warmer world that amount will only increase. Allowing further warming to take place simply makes an already bad situation worse.

Please use this form to provide feedback about this new "At a glance" section. Read a more technical version below or dig deeper via the tabs above!

Further details

The current research into the effects of climate change on tropical storms demonstrates the virtues and transparency of the scientific method at work. It also rebuts the oft-aired conspiracy-theory that scientists fit their findings to a predetermined agenda in support of climate change. They must be exceptionally good at it if that's the case. Normally a single Presidential term does not pass without various people leaking various things that would preferably be kept quiet. In the case of climate change, for this conspiracy theory to be even half-correct, they would have needed to keep it going without fail for two whole centuries! File under 'impossible expectations'.

In the case of storm frequency, there is no consensus and reputable scientists have two diametrically opposed hypotheses about increasing or decreasing frequencies of such events. The IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) therefore ascribes 'medium confidence' on the frequency of tropical systems remaining the same or decreasing a little. That basically means "we don't entirely know at the moment".

The background to these inquiries stems from a simple observation: extra heat in the air or the oceans is extra energy, and storms are driven by such fuel. What we do not know is whether we might see more storms as a result of extra energy or, as other researchers conclude, the storms may grow more intense. There is a growing body of evidence that since the mid-1970s, storms have been increasing in strength, and therefore severity. Looking forward, in a world that continues to warm, even more energy means storms will be more destructive, last longer and make landfall more frequently than in the past. AR6 gives increasing intensity a 'likely'. Because this phenomenon is strongly associated with sea surface temperatures (fig. 1), it is reasonable to expect that the increase in storm intensity and climate change are linked.

Fig. 1:the warm (and warming) tropical seas are the spawning-ground for hurricanes. Graphic: NASA.

Winds are just one impact of a hurricane: the other is flooding, from two key sources: firstly, storm surges and secondly, extreme rainfalls.

Like any deep area of low pressure, hurricanes have a sizable bulge of sea beneath their eye, accompanying them as they track along. This bulge - the storm surge - forms due to the phenomenally low pressure at the centre of such a storm, that may even fall below 900 millibars in some cases.

Damage caused by a storm surge is dependent on its size, forward speed, sea bed topography, coastal land altitude, whether it strikes at low or high tide and the size of the tide, controlled by the tidal cycle. Spring tides are the biggest and don't just happen in the spring: they occur twice a month. A worst-case scenario occurs where the following factors combine:

- the sea-bed abruptly changes landward from deep to shallow

- the coastal land is low-lying and populous

- the surge hits at high water on a spring tide

- the storm's central pressure is exceptionally low i.e. a Category 5 system

- the storm's forward motion is rapid

If that combination occurs, the damage can be tsunami-like in its effects. A trend towards more intense storms making landfall in a warmer world is therefore a matter of major concern. Add rising sea levels into the mix and one can clearly see the future potential for big trouble due to such surges.

Rainfall is the second source of misery and destruction in tropical systems and in most cases is the leading one. It's worth quoting directly from AR6 with regard to intense rainfalls:

"The average and maximum rain rates associated with tropical cyclones (TCs), extratropical cyclones and atmospheric rivers across the globe, and severe convective storms in some regions, increase in a warming world (high confidence)."

A simple formula (the Clausius-Clapeyron relation) expresses how warmer air is able to transport more moisture. The increased capacity is 7% more per degree Celsius of air temperature increase - something that's been understood since the 1850s. Provided a tropical system has access to increased heat and moisture as it tracks over Earth's ocean surface, it's guaranteed to drop more rainfall in a warmer world. The same principle explains why such systems start to disperse after landfall: that heat and moisture supply gets cut off and they lose their energy-source.

Note that the IPCC makes specific reference to rainfall rates. This is very important. If an inch of rain falls over 24 hours you might see rivers slowly going into spate. But if that same amount falls in just half an hour, you see news headlines regarding properties affected by flash-flooding.

So to conclude, there are things that are almost certain with regard to hurricane frequency, severity and impacts, but there are other things about which we don’t know for sure yet. What can we conclude? About hurricane frequency – not much; the jury is still out. About severity, they do seem to be packing stronger winds. About impacts, stronger winds, faster intensification and a trend of increasingly-severe flooding all seem likely.

With regard to the contested hypotheses about absolute frequency of tropical storms and climate change, we can say that these differing hypotheses are the very stuff of good science, and in this microcosm of climatology, the science is clearly not yet settled. It is also obvious that researchers are not shying away from refuting associations with climate change where none can be found. We can safely assume they don’t think their funding or salaries are jeopardised by publishing research into a serious problem that does not in some way implicate climate change!

Last updated on 3 July 2024 by John Mason. View Archives

Arguments

Arguments

More articles of note:

Four little discussed ways that climate change could make hurricanes even worse by Chris Mooney, Energy & Environment, Washington Post, Sep 11, 2017

How global warming could push hurricanes to new regions by Bob Berwyn, Pacific Standard, Sep 11, 2017

'I Don't Expect The Season To Be Done': A Hurricane Expert On What's Still To Come by Kate Wheeling, Pacific Standard, Sep 12, 2017

A new article with some background at Science of Doom:

Impacts – XIV – Tropical Cyclones and Climate Change 1

Kevin Walsh and coauthors in 2016: "At present, there is no climate theory that can predict the formation rate of tropical cyclones from the mean climate state"

In general, relative SST (local sea surface temperature minus the tropical mean sea surface temperature) being more important than absolute SST for TC development has the weight of climate scientists behind it.

Climate models struggle to reproduce the more intense TCs (tropical cyclones) in the recent climate and papers come with many caveats about the difficulties of predicting the future.

Another argument about gw and hurricanes is that the latter will work as a negative/damping feedback on the former, since hurricanes transfer energy out to space (among other places), and the more intense the hurricanes become, the more energy they will transfer. I'm trying to find reliable numbers to show that to the extent that this might happen, it is insignificant compared to the approximately half-million A-bombs worth of extra energy ghg's are preventing from gettin into space every day.

I don't see this in the already-long list of denialist arguments, but maybe I missed it?

wili @78,

I did have some useful NOAA(?) numbers for the energy fluxes associated with tropical cyclones but they are not falling to hand. However there is literature that presents data. Although this is a bit less authoritative-looking, the literature (& this is from papers to hand rather than from a proper search) does seem quite definitive that hurricanes act to warm the planet rather than cool it although the mechanisms are not that simple.

Tropical cyclones do simplistically pump energy out of the ocean which will cool the planet. They also mix warm surface waters down into the ocean which, as the post-cyclone surface is cooler and thus easier to warm, will allow ocean warming. (These hurricane-warmed ocean depths won't just sit there but will enhance poleward heat fluxes, as discussed below.) The net size of the ocean-atmosphere flux from global tropical cyclones has been assessed globally using ARGO data at +1.9PW during the passage of storms but becomes a net negative -0.3PW when subsequent enhanced warming following the storm is included. The global figures when divided between hurricanes and lesser storms shows that it is hurricanes which are responsible for the net total being negative (Net total for just hurricanes equals 0.75PW cooling = a global 1.5Wm^-2), with 0.8PW of ocean cooling during the storm but followed by 1.5PW of subsequent ocean warming. For lesser storms the net ocean cooling remains positive 1.0PW cooling during the storm with 0.6 subsequent warming. This suggests that in a world with more hurricanes but fewer less-powerful tropical storms (a possibility that many denialists deny), there will be as a result bigger heat fluxes into the oceans.

A further mechanism for cooling the planet is that the ocean mixing caused by tropical cyclones will impact poleward heat transfer to some extent, enhancing it in the oceans, reducing it in the atmosphere. But when the effect is set up in a climate model, the impact becomes a net warming effect due to the spread of humid atmospheres and such-like. So, of the ~2ºC global warming resulting from poleward heat fluxes (which are roughly 5 PW in each direction), perhaps some 0.2ºC results from tropical cyclones and would be boosted by increased cyclone activity. (That could be equated to a climate forcing using ECS=3 of +0.25Wm^-2).

So in terms of A-bombs, the increase in that +0.25Wm^-2 of warming from today's tropical cyclones will be small and will also be A minus.

Recommended supplemental readings...

How to talk about hurricanes now by John D Sutter, Health, CNN, Oct 10, 2018

The Hurricanes, and Climate-Change Questions, Keep Coming. Yes, They’re Linked. by Henry Fountain, Climate, New York Times, Oct 10, 2018

Is climate change making hurricanes worse? by Daniel Levitt & Niko Kommenda, Weather, Guardian, Oct 10, 2018

Yes, Hurricane Michael is a climate change story by Pete Vernon, Columbia Journalism Review (CJR), Oct 12, 2018

Note: The Daniel Levitt & Niko Kommenda article include outstanding graphics.

Did anyone here respond to the recent article in Nature apparently documenting that hurricanes in the US have shown no trend, either in frequency or intensity or (the authors' index of) damage caused?

And while I'm asking, thegwpf.org recently published a compilation of stats on global cyclones that seems to show the same pattern so far globally. (This one NOT peer reviewed or published in maybe the most prestigious scientific journal.)

Sorry, rookie error. I refreshed the page to see if anything had changed and my browser entered my post again. And I don't see how to delete the duplicate.

[DB] While the moderators usually notice, should it happen again just ask for the duplicate to be removed.

Norm Rubin,

Can you link the article you are talking about so we can find it?

@ Norm Rubin #82

Here's one response to pseudo-science poppycock written by Paul Homewood and posted on the GWPF website:

GWPF’s “Incoherent” Climate Reports Misrepresent IPCC; Chairman’s Resignation Unrelated, ClimateDenierRoundup, DailyKos, Jan 18, 2019

All I can find this minute is the abstract and citation with the full text behind Nature's paywall. I thought I'd read it but I've never paid for a Nature subscription

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-018-0165-2 is the link.

And here's a paste of the contents, FWIW:

I believe the item linked in post 84 is aimed at the second item I was asking about

[DB] A full copy is here.

Norm Rubin,

I am not an expert on hurricanes but I read some.

Nature Sustainability is not the same journal as Nature. It is less prestigious.

These authors have been making this argument for a long time. From what I have read it appears that they are in the minority but there is not a consensus on this topc.

Analysis of USA only data seems inappropriate to me. There are not many hurricanes and the record is noisy. The USA is only 3% of the Earth's surface. You would expect that noise would be bigger than the signal.

This article documents that strong hurricanes (force 4 and 5) have increased in number over the entire Earth. They reference at least 4 other papers that find an increase in the most powerful hurricanes. There appear to be less force 1 and 2 hurricanes so the total number of hurricanes is about the same. There is much more signal to noise in an analysis of the entire Earth. It stands to reason that if there are more force 4 and 5 hurricanes (which cause most of the damage), there will be more damage caused. An analysis of world wide damage for the past 40 years would be more meaningful than a USA only analysis with a longer record.

The paper I cited claims that sea surface temperatures have only been elevated enough to affect hurricanes for 40 years so the earlier data in your cited paper is not as valuable.

Jeff Masters discusses the catastrophic hurricanes that struck the USA in 2018. He discusses modeling that attributes 50% of Florence's rainfall to warming. Similar attribution has been made for Harvey's rainfall in Texas last year.

To me it stands to reason that if there are more category 4 and 5 hurricanes and they produce twice as much rain due to warming than more damage will be caused by hurricanes. There were several strong hurricanes at the start of the limited USA record analyzed in the Weinkle et al paper which affect the statistics.

I expect it to be a long time (decades) before the USA only record of hurricanes shows statistically significant change in hurricanes since there are so few and the record is noisy. The worldwide record already shows increases in powerful hurricanes which cause the most damage.

I doubt there will be much commentary on this paper by scientists unless deniers make wild claims about it. Since it is a valid paper if you choose to make the argument that hurricanes have not changed you can, but it is not a strong claim when the world record is examined. The fact the US damage was so severe in 2018, after the Weinkle paper was published, is suggestive but not statistically significant yet.

Somewhat old now, but Pielke's work has been discussed over at Tamino's Open MInd in the past:

https://tamino.wordpress.com/2012/11/03/catastrophes-how-many-more/

https://tamino.wordpress.com/2012/11/03/unnatural-catastrophes/

Slightly newer discussion of hurrixcane frequency at RealClimate. The post presents some behaviour by Pielke that is, shall we say, not particularly flattering.

http://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2014/03/the-most-common-fallacy-in-discussing-extreme-weather-events/

Norm Rubin,

The RealClimate link that Bob Loblaw has above shows that using only landfalling hurricanes reduces the available data by a factor of over 1000. They specifically argue that this is an inappropriate method of data analysis because it allows the noise to overcome the signal. It appears that the paper you cited has been prebunked. I seem to have been too kind in my post.

Bob,

Thanks for the great links. I see your posts on other sites. Always well informed.

Thanks folks, that's what I was looking for. More the science and stats part than the ad hominem stuff, since I was raised to be able to learn from a fool, and I also don't mind learning from people who are biased or sometimes wrong I try to avoid tribalism in politics generally, and I find it especially rampant and ugly in the climate wars.

But it will take me a while to get through it all.

Just offhand, of course the US mainland is not nearly the whole world, but it's probably the part that's been keeping the best records of hurricanes for the longest. When you lose your keys in the dark, it may be smart to look first under the streetlights, type thing. Of course, of all possible statistical outcomes, a finding of no significant trend is most easily produced by a too-small sample, so I "get" the criticism.

Norm Rubin:

Hot off the press:

4 Climate-Influenced Disasters Cost the U.S. $53 Billion in 2018 by Daniel Cusick, E&E News/Scientific American, Jan 23, 2019

GPWayne

Thank you for the rebuttal regarding frequency of tropical storms. Could you please comment on this 2017 article [Truchelut, R.E. and Staehling, E.M. 2017. An energetic perspective on United States tropical cyclone landfall droughts. Geophysical Research Letters 44: 12,013-12,019.] which is cited by climate skeptic websites? It claims there was a drought of energetic hurricanes; i.e. hurricanes above a Cyclone Energy of 100 kt, from 2006 to 2015. It also claims "a statistically significant downward trend since 1950, with the percentage of total Atlantic Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) expended over the continental U.S. at a series minimum during the recent drought period." On the face of it, ACE sounds like a good measure of hurricane activity.

Thanks in advance for your response

Current global ACE is 103% of normal.

Whats Up With That???

https://policlimate.com/tropical/

Denier blogs lie. Do not trust them.

Ritchieb,

Strong hurricanes are not very common events. The USA is only about 3% of world surface area. You expect a lot of year to year variation in rare occurances measured over a small area. That includes periods of lower activity. The global trend is more very strong hurricanes (along with more weak hurricanes and less moderate hurricanes).

From your reference:

"The 2017 Atlantic hurricane season has been extremely active both in terms of the strength of the tropical cyclones that have developed and the amount of storm activity that has occurred near the United States. This is even more notable as it comes at the end of an extended period of below normal U.S. hurricane activity, as no major (category 3 or higher) hurricanes made landfall from 2006 through 2016."

If the deniers are claiming that there are less strong hurricanes hitting the USA because of AGW (or whatever reason they propose) they have to also note the large damages in the past three years. I note that Hurricane Sandy was not a major hurricane when it hit New York and occured during the "Hurricane drought", along with other very damaging storms. I doubt that New Yorkers consider 2012 a "major hurricane free" year. In addition, hurricane forward speed has decreased worldwide causing much greater flooding (like Harvy, Barry and TS Imelda). That appears to be AGW linked.

Scientifically it is interesting to seek explainations for unusual events. Random chance is the best explaination for this issue.

Please note: the basic version of this rebuttal was updated on May 19, 2024 and now includes an "at a glance“ section at the top. To learn more about these updates and how you can help with evaluating their effectiveness, please check out the accompanying blog post @ https://sks.to/at-a-glance